Chapter 7 | Don and Jem Go Home to Tea | The Adventures of Don Lavington

It required no little effort on Don’s part to go home that afternoon to the customary meat tea which was the main meal of the day at his uncle’s home.

He felt how it would be—that his uncle would not speak to him beyond saying a few distant words, such as were absolutely necessary. Kitty would avert her eyes, and his mother keep giving him reproachful looks, every one of which was a silent prayer to him to speak.

The afternoon had worn away, and he had done little work for thinking. His uncle had not been back, and at last Jem’s footstep was heard outside, and he passed the window to tap lightly on the door and then open it.

“Come, Mas’ Don,” he said, cheerily, “going to work all night?”

“No, Jem, no. I was just thinking of going.”

“That’s right, my lad, because it’s past shutting-up time. Feel better now, don’t you?”

“No, Jem, I feel worse.”

“Are you going to keep the yard open all the evening, Jem?” cried a shrill voice. “Why don’t you lock-up and come in to tea?”

“There! Hear that!” said Jem, anxiously. “Do go, Mas’ Don, or I sha’n’t get to the end on it. ’Nuff to make a man talk as you do.”

“Jem!”

“Here, I’m a-coming, arn’t I?” he cried, giving the door a thump with his fist. “Don’t shout the ware’us down!”

“Jem!”

“Now did you ever hear such a aggrawatin’ woman?” cried Jem. “She’s such a little un that I could pick her up, same as you do a kitten, Mas’ Don—nothing on her as you may say; but the works as is inside her is that strong that I’m ’fraid of her.”

“Jem!”

He opened the door with a rush.

“Ya–a–a–as!” he roared; “don’t you know as Mas’ Don arn’t gone?”

Little Mrs Wimble, who was coming fiercely up, flounced round, and the wind of her skirts whirled up a dust of scraps of matting and cooper’s chips as she went back to the cottage.

“See that, Mas’ Don? Now you think you’ve all the trouble in the world on your shoulders, but look at me. Talk about a woman’s temper turning the milk sour in a house. Why, just now there’s about three hundred hogsheads o’ sugar in our ware’us—two hundred and ninety-three, and four damages not quite full, which is as good as saying three hundred—see the books whether I arn’t right. Well, Mas’ Don, I tell you for the truth that I quite frights it—I do, indeed—as she’ll turn all that there sweetness into sour varjus ’fore she’s done. Going, sir?”

“Yes, Jem, I’m going—home,” said Don; and then to himself, “Ah, I wish I had a home.”

“Poor Mas’ Don!” said Jem, as he watched the lad go out through the gate; “he’s down in the dumps now, and no mistake; and dumps is the lot o’ all on us, more or less.”

Then Jem went in to his tea, and Don went slowly home to his, and matters were exactly as he had foreseen. His uncle was scarcely polite; Kitty gave him sharp, indignant glances when their eyes met, and then averted hers; and from time to time his mother looked at him in so pitiful and imploring a manner that one moment he felt as if he were an utter scoundrel, and the next that he would do anything to take her in his arms and try and convince her that he was not so bad as she thought.

It was a curious mental encounter between pride, obstinacy, and the better feelings of his nature; and unfortunately the former won, for soon after the meal was over he hurried out of the room.

“I can’t bear it,” he cried to himself, as he went up to his own little chamber,—“I can’t bear it, and I will not. Every one’s against me. If I stop I shall be punished, and I can’t face all that to-morrow. Good-bye, mother. Some day you’ll think differently, and be sorry for all this injustice, and then—”

A tear moistened Don’s eye as he thought of his mother and her tender, loving ways, and of what a pity it was that they ever came there to his uncle’s, and it was not the tear that made Don see so blindly.

“I can’t stand it, and I will not,” he cried, passionately. “Uncle hates me, and Mike Bannock’s right, scoundrel as he is. Uncle has robbed me, and I’ll go and fight for myself in the world, and when I get well off I’ll come back and seize him by the throat and make him give up all he has taken.”

Don talked to himself a good deal more of this nonsense, and then, with his mind fully made up, he went to the chest of drawers, took out a handkerchief, spread it open upon the bed, and placed in it a couple of clean shirts and three or four pairs of stockings.

“There,” he said, as he tied them up tightly as small as he could, “I won’t have any more. I’ll go and start fair, so that I can be independent and be beholden to nobody.”

Tucking the bundle under his arm, he could not help feeling that it was a very prominent-looking package—the great checked blue and white handkerchief seeming to say, “This boy’s going to seek his fortune!” and he wished that he was not obliged to take it.

But, setting his teeth, he left the room with the drawers open, and his best suit, which he had felt disposed to take, tossed on a chair, and then began to descend.

It was a glorious summer evening, and though he was in dirty, smoky Bristol, everything seemed to look bright and attractive, and to produce a sensation of low-spiritedness such as he had never felt before.

He descended and passed his mother’s room, and then went down more slowly, for he could hear the murmur of voices in the dining-room, which he had to pass to reach the front door, outside which he did not care what happened; but now he had to pass that dining-room, and go along the passage and by the stand upon which his cocked hat hung.

It was nervous work, but he went on down the first flight, running his hand slowly along the hand-balustrade, all down which he had so often slid while Kitty looked on laughing, and yet alarmed lest he should fall. And what a long time ago that seemed!

He had just reached the bottom flight, and was wondering what to say if the door should open and his uncle meet him with the blue bundle under his arm, when the dining-room door did open, and he dashed back to the landing and stood in the doorway of his mother’s room, listening as a step was heard upon the stairs.

“Kitty!” he said to himself, as he thrust against the door, which yielded to his pressure, and he backed in softly till he could push the door to, and stand inside, watching through the crack.

There was the light, soft step coming up and up, and his heart began to beat, he knew not why, till something seemed to rise in his throat, and made his breath come short and painfully.

His mother!

She was coming to her room, and in another moment she would be there, and would find him with the bundle under his arm, about to run away.

Quick as thought he looked sharply round, bundle in hand, when, obeying the first impulse, he was about to push it beneath the bedclothes, but cast aside the plan because he felt that it would be noticed, and quick as thought he tossed the light bundle up on the top of the great canopy of the old-fashioned bedstead, to lie among the gathering of flue and dust.

By that time the footsteps were at the door.

“What shall I say?” Don asked himself; “she will want to know why I am here.”

He felt confused, and rack his brains as he would, no excuse would come.

But it was not wanted, for the light footstep with the rustle of silk passed on upstairs, and Don opened the door slightly to listen. His breath came thickly with emotion as he realised where his mother had gone. It was to his bedroom door, and as he listened he heard her tap lightly.

“Don! Don, my boy!” came in low, gentle tones.

For one moment the boy’s heart prompted him to rush up and fling himself in her arms, but again his worse half suggested that he was to be scolded and disbelieved, and mentally thrusting his fingers into his ears, he stepped out, glided down the staircase in the old boyish fashion of sliding down the banister, snatched his hat from the stand, and softly stole out to hurry down the street as hard as he could go.

He had been walking swiftly some five minutes, moved by only one desire—that of getting away from the house—when he awoke to the fact that he was going straight towards the constable’s quarters and the old-fashioned lock-up where Mike must be lying, getting rid of the consequences of his holiday-making that morning.

Don turned sharply round in another direction, one which led him towards the wharves where the shipping lay.

While this was taking place, Jem Wimble had been banging the doors and rattling his keys as he locked up the various stores, feeling particularly proud and self-satisfied with the confidence placed in him.

After this was done he had a wash at the pump, fetching a piece of soap from a ledge inside the workshop where the cooper’s tools were kept, and when he had duly rubbed and scrubbed and dried his face and hands, he went indoors to stare with astonishment, for his little wife was making the most of her size by sitting very upright as she finished her tea.

Jem plumped himself indignantly down, and began his. This was a new annoyance. Sally had scolded times out of number, and found fault with him for being so late, but this was the first time that she had ever begun a meal without his being present, and he felt bitterly hurt.

“As if I could help it,” he said, half aloud. “A man has his work to do, and he must do it.”

“Five o’clock’s tea-time, and you ought to have been here.”

“And if I wasn’t here, it was your dooty to wait for me, marm.”

“Was it?” cried Sally; “then I wasn’t going to. I’m not going to be ordered about and ill-treated, Jem; you always said you liked your tea ready at five o’clock. I had it ready at five o’clock, and I waited till half-past, and it’s now five-and-twenty to six.”

“I don’t care if it’s five-and-twenty to nineteen!” cried Jem angrily. “It’s your dooty to wait, same as it’s mine to shut up.”

“You might have shut up after tea.”

“Then I wasn’t going to, marm.”

“Then you may have your tea by yourself, for I’ve done, and I’m not going to be trampled upon by you.”

Sally had risen in the loudness of her voice, in her temper, and in her person, for she had got up from her chair; but neither elevation was great; in fact, the personal height was very small, and there was something very kittenish and comic in her appearance, as she crossed the bright little kitchen to the door at the flight of stairs, and passing through, banged it behind her, and went up to her room.

“Very well,” said Jem, as he sat staring at the door; “very well, marm. So this is being married. My father used to say that if two people as is married can’t agree, they ought to divide the house between ’em, but one ought to take the outside and t’other the in. That’s what I’m a-going to do, only, seeing what a bit of a doll of a thing you are, and being above it, I’m going to take the outside myself. There’s coffee bags enough to make a man a good bed up in the ware’us, and it won’t be the first time I’ve shifted for myself, so I shall stop away till you fetches me back. Do you hear?”

“Oh, yes, I can hear,” replied Sally from the top of the stairs, Jem having shouted his last speech.

“All right, then,” said Jem: “so now we understands each other and can go ahead.”

Tightening up his lips, Jem rinsed out the slop-basin, shovelled in a good heap of sugar, and then proceeded to empty the teapot, holding the lid in its place with one fat finger the while.

This done, he emptied the little milk jug also, stirred all well up together, and left it for a few minutes to cool, what time he took the cottage loaf from the white, well-scrubbed trencher, pulled it in two, took a handful of bread out of one half, and raising the lump of fresh Somersetshire butter on the point of a knife, he dabbed it into the hole he had made in the centre, shut it up by replacing the other half of the bread, and then taking out his handkerchief spread it upon his knee and tied the loaf tightly therein. Then for a moment or two he hesitated about taking the knife, but finally concluding that the clasp knife in his pocket would do, he laid the blade on the table, gave his tea a final stir, gulped down the basinful, tucked the loaf in the handkerchief under his left arm, his hat very much on one side, and then walked out and through the gate, which he closed with a loud bang.

“Oh!” ejaculated Sally, who had run to the bedroom window, “he has gone!”

Sally was quite right, Jem, her husband, was gone away to his favourite place for smoking a pipe, down on the West Main wharf, where he seated himself on a stone mooring post, placed the bundle containing the loaf beside him, and then began to eat heartily? Nothing of the kind. Jem was thinking very hard about home and his little petulant, girlish wife.

Then he started and stared.

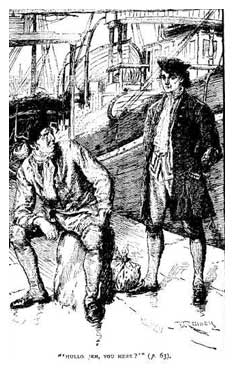

“Hullo, Jem, you here?”

“Why, Mas’ Don, I thought you was at home having your tea.”

“I thought you were having yours, Jem.”

“No, Mas’ Don,” said Jem sadly; “there’s my tea”—and he pointed to the bundle handkerchief; “there’s my tea; leastwise I will tell the truth, o’ course—there’s part on it; t’other part’s inside, for I couldn’t tie that up, or I’d ha’ brought it same ways to have down here and look at the ships.”

“Then why don’t you eat it, man?”

“’Cause I can’t, sir. I’ve had so much o’ my Sally that I don’t want no wittals.”

Don said nothing, but sat down by Jem Wimble to look at the ships.