Chapter 4 | Mike Bannock has a Ride | The Adventures of Don Lavington

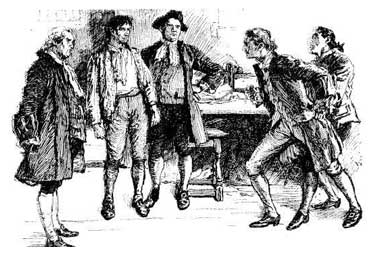

“You wretch!”

Those two words were a long time coming, but when they did escape from Lindon’s lips, they made up in emphasis and force for their brevity.

“Steady, Master Don, steady,” said Jem, throwing his arms round the boy’s waist, and holding him back. “You arn’t strong enough to fight him.”

“Wretch? Oh! Well, I like that. Why, some men would ha’ gone straight to your uncle here, and told him all about it; but I didn’t, and I’d made up my mind to send him the money back, only I met two or three mates, and I had to change one of ’em to give the poor lads a drink o’ ale.”

“You own, then, that you had my money, sir?” cried the old merchant.

“Well—some on it, master. He give it me. S’pose I oughtn’t to have took it, but I didn’t like to come and tell you, and get the poor lad into trouble. He’s so young, you see.”

“Uncle, it is not true!” cried Lindon, excitedly.

“But you had one of the guineas in your pocket, sir.”

“Yes, uncle, but—”

“Course he had,” interrupted Mike sharply. “I told you it wouldn’t do, Master Don. I begged you not to.”

“You villain!” cried Don, grinding his teeth, while his uncle watched him with a sidelong look.

“Calling names won’t mend it, my lad. I knowed it was wrong. I telled him not to, sir, but he would.”

This was to the constable in a confidential tone, and that functionary responded with a solemn wink.

“It is not true, uncle!” cried Don again.

“Oh, come now,” said Mike, shaking his head with half tipsy reproach, “I wouldn’t make worse on it, my lad, by telling a lot o’ lies. You did wrong, as I says to you at the time; but you was so orbst’nate you would. Says as you’d got such lots of money, master, as you’d never miss it.”

Uncle Josiah gave vent to a sound resembling a disgusted grunt, and turned from the speaker, who continued reproachfully to Don,—

“What you’ve got to do, my lad, is to go down on your bended knees to your uncle, as is a good master as ever lived—and I will say that, come what may—and ask him to let you off this time, and you won’t do so any more.”

“Uncle, you won’t believe what he says?” cried Don wildly.

Uncle Josiah did not reply, only looked at him searchingly.

“He can’t help believing it, my lad,” said Mike sadly. “It’s werry shocking in one so young.”

Don made a desperate struggle to free himself from Jem’s encircling arms, but the man held fast.

“No, no, my lad; keep quiet,” growled Jem. “I’m going to spoil the shape of his nose for him before he goes.”

“Then you don’t believe it, Jem?” cried Don, passionately.

“Believe it, my lad? Why, I couldn’t believe it if he swore it ’fore a hundred million magistrits.”

“No, that’s allus the way with higgerant chaps like you, Jem Wimble,” said Mike; “but it’s all true, genelmen, and I’m sorry I didn’t speak out afore like a man, for he don’t deserve what I did for him.”

“Hah!” ejaculated Uncle Josiah, and Don’s face was full of despair.

“You charge Mike Bannock, then, with stealing this money, sir,” said the constable.

“Yes, certainly.”

“What?” roared Mike, savagely, “charge me?”

“That will do,” said the constable, taking a little staff with a brass crown on the end from his pocket. “No nonsense, or I shall call in help. In the King’s name, my lad. Do you give in?”

“Give in? What for? I arn’t done nothing. Charge him; he’s the thief.”

Don started as if the word thief were a stinging lash.

Jem loosed his hold, and with double fists dashed at the scoundrel.

“You say Master Don’s a thief!”

“Silence, Wimble! Stand back, sir,” cried Uncle Josiah, sternly.

“But, sir—”

“Silence, man! Am I master here?”

Jem drew back muttering.

“Charge him, I say,” continued Mike, boisterously; “and if you won’t, I will. Look here, Mr Smithers, I charge this ’ere boy with going to his uncle’s desk and taking all the gold, and leaving all the silver in a little hogamee bowl.”

“You seem to know all about it, Mike,” said the constable, grimly.

“Course I do, my lad. I seed him. Caught him in the werry act, and he dropped one o’ the guineas, and it run away under the desk, and he couldn’t find it.”

“You saw all that, eh?” said the constable.

“Every bit of it. I swears to it, sir.”

“And how came you to be in the office to see it?”

“How come I in the office to see it?” said Mike, staring; “how come I in the office to see it?”

“Yes. Your work’s in the yard, isn’t it?”

“Course it is,” said Mike, with plenty of effrontery; “but I heerd the money jingling like, and I went in to see.”

“And very kind of you too, Mike,” said the constable, jocularly. “Don’t you forget to tell that to the magistrates.”

“Magistrits? What magistrits? Master arn’t going to give me in custody, I know.”

“Indeed, but I am, you scoundrel,” cried Uncle Josiah, wrathfully. “You are one of the worst kind of thieves—”

“Here, take that back, master.”

“Worst kind of scoundrels—dogs who bite the hand that has fed them.”

“I tell yer it was him,” said Mike, with a ferocious glare at Don.

“All right, Mike, you tell the magistrates that,” said the constable, “and don’t forget.”

“I arn’t going ’fore no magistrits,” grumbled Mike.

“Yes, you are,” said the constable, taking a pair of handcuffs from his pocket. “Now then, is it to be quietly?”

Mike made a furious gesture.

“Just as you like,” said the constable. “Jem Wimble, I call you in the King’s name to help.”

“Which I just will,” cried Jem, with alacrity; and he made at Mike, while Don felt a strange desire tingling in his veins as he longed to help as well.

“I gives in,” growled Mike. “I could chuck the whole lot on you outer winder, but I won’t. It would only make it seem as if I was guilty, and it’s not guilty, and so I tell you. Master says I took the money, and I says it was that young Don Lavington as is the thief. Come on, youngster. I’ll talk to you when we’re in the lock-up.”

Don looked wildly from Mike to his uncle, whose eyes were fixed on the constable.

“Do you charge the boy too, sir?”

Uncle Josiah was silent for some moments.

“No! Not now!”

Lindon’s heart leapt at that word “no!” But it sank again at the “not now.”

“But the case is awkward, sir,” said the constable. “After what this man has said we shall be obliged to take some notice of the matter.”

“’Bliged to? Course you will. Here, bring ’im along. Come on, mate. I can tell you stories all night now about my bygones. Keep up yer sperrits, and I daresay the magistrits ’ll let you off pretty easy.”

“If there is any charge made against my young clerk,”—Don winced, for his uncle did not say, “against my nephew,”—“I will be answerable for his appearance before the magistrates. That will be sufficient, I presume.”

“Yes, sir, I suppose that will do,” said the constable.

“But I s’pose it won’t,” said Mike. “He’s the monkey and I’m only the cat. You’ve got to take him if you does your dooty, and master ’ll be answerable for me.”

“Exactly,” said the constable; “come along.”

“Nay, but this arn’t fair, master. Take one, take all. You bring us both.”

“Come along.”

“If you don’t bring that there young un too, I won’t go,” exclaimed the scoundrel, fiercely.

Click!

A short struggle, and then click again, and Mike Bannock’s hands were useless, but he threw himself down.

“Fair play, fair play,” he cried, savagely; “take one, take all. Are you going to charge him, master?”

“Take the scoundrel away, Smithers, and once more I will be bail—before the magistrates, if necessary—for my clerk’s appearance,” cried Uncle Josiah, who was now out of patience. “Can I help?”

“Well, sir, you could,” said the constable, grimly; “but if you’d have in three or four of your men, and a short step ladder, we could soon carry him off.”

“No man sha’n’t carry me off,” roared Mike, as Jem ran out of the office with great alacrity, and returned in a very short time with three men and a stout ladder, about nine feet long.

“That’s the sort, Wimble,” said the constable. “Didn’t think of a rope, did you?”

“Did I think of two ropes?” said Jem, grinning.

“Ah!” ejaculated the constable. “Now, Mike Bannock, I just warn you that any violence will make your case worse. Take my advice, get up and come quietly.”

“Take young Don Lavington too, then, and I will.”

“Get up, and walk quietly.”

“Not ’less you takes him.”

“Sorry to make a rumpus, sir,” said the constable, apologetically; “but I must have him out.”

“The sooner the better,” said Uncle Josiah, grimly.

“I am ready to go, uncle,” said Don, quietly. “I am not afraid.”

“Hold your tongue, sir!” said the merchant, sternly; “and stand out of the way.”

“Now, Mike,” said the constable, “this is the third time of asking. Will you come quiet?”

“Take him too,” cried Mike.

“Ready with those ropes, Wimble. You two, ready with that there. Now, Mike Bannock, you’ve been asked three times, and now you’ve got to mount that ladder.”

“Any man comes a-nigh me,” roared Mike, “I’ll—”

He did not say what, for the constable dashed at him, and by an ingenious twist avoided a savage kick, threw the scoundrel over on his face, as he lay on the floor, and sat upon him, retaining his seat in spite of his struggles.

“Step the first,” said the constable, coolly. “Now, Wimble, I want that ladder passed under me, so as to lie right along on his back. Do you see?”

“Yes, sir,” cried Jem, eagerly; and taking the ladder as the constable sat astride the prostrate scoundrel, holding down his shoulders, and easing himself up, the ladder was passed between the officer’s legs, and, in spite of a good deal of heaving, savage kicking, and one or two fierce attempts to bite, right along till it was upon Mike’s back, projecting nearly two feet beyond his head and feet.

“Murder!” yelled Mike, hoarsely.

“What? Does it hurt, my lad? Never mind; you’ll soon get used to it.”

The constable seated himself upon the ladder, whose sides and rounds thoroughly imprisoned the scoundrel in spite of his yells and struggles to get free.

“Now then, Wimble, I’ve got him. You tie his ankles, one each side, tightly to the ladder, and one of you bind his arms same way to the ladder sides. Cut the rope. Mr Christmas will not mind.”

The men grinned, and set to work so handily that in a few moments Mike was securely bound.

“Now then,” said the constable, “I’ll have one round his middle; give me a piece of rope; I’ll soon do that.”

He seized the rope, and, without rising, rapidly secured it to one side of the ladder.

“Now,” he said, “raise that end.”

This was done, the rope passed under Mike, drawn up on the other side, hauled upon till Mike yelled for mercy, and then knotted twice.

“There, my lads,” said the constable, rising; “now turn him over.”

The ladder was seized, turned, and there lay Mike on his back, safely secured.

“Here, undo these,” he said, sullenly. “I’ll walk.”

“Too late, Mike, my boy. Now then, a couple of men head and tail. Let the ladder hang at arm’s length. Best have given in quietly, and not have made yourself a show, Mike.”

“Don’t I tell you I’ll walk?” growled the prisoner. “And let us have all our trouble for nothing? No, my lad, it’s too late. Ready there! Up with him. Good morning, sir. March!”

The men lent themselves eagerly to the task, for Mike was thoroughly disliked; and a few minutes later there was a crowd gathering and following Mike Bannock as he was borne off, spread-eagled and half tipsy, to ponder on the theft and his chances in the cold damp place known in Bristol as the lock-up.

Don Lavington stood in the office, waiting for his uncle to speak.