Chapter 52 | Don Has a Headache | The Adventures of Don Lavington

“Escaped from the Maoris, and then from a party of men you think were runaway convicts?” said the broad-shouldered, sturdy occupant of the little farm which they reached just at dusk. “Ah, well, we can talk about that to-morrow, my lads. It’s enough for me that you are Englishmen. Come in.”

“I cannot leave our friend,” said Don quietly, as he laid his hand on Ngati’s arm.

“What, the savage!” said the farmer, rubbing his ear. “Well, we—oh, if he’s your friend, that’s enough.”

They had no occasion to complain of the hospitality, for the farmer, who had been settled there, with a few companions only, for about four years, was but too glad to see fresh faces, and with a delicacy hardly to be expected from one leading so rough a life he refrained from asking any questions.

Don was glad, for the next morning he rose with a peculiar aching sensation in the head, accompanied by alternate fits of heat and cold.

The next day he was worse, but he kept it to himself, laughing it off when they noticed that he did not eat his breakfast, and, to avoid further questioning, he went out after a time to wander up the valley into the shady woodland and among the tree-ferns, hoping that the rest and cool shadowy calm of the primaeval forest would prove restful and refreshing.

The day was glorious, and Don lay back listening to the cries of the birds, dreaming of home, and at times dozing off to sleep after his restless night.

His head ached terribly, and was confused, and at times, as he lay back resting against a tuft of fern, he seemed to be back at Bristol; then in an instant he thought he must be in the Maoris’ pah, wondering whether there could be any truth in Jem’s fancies as to why they were being kept.

Then there was a dull time of blank weariness, during which he saw nothing, till he seemed to be back in the convicts’ lurking-place, and he saw Mike Bannock thrusting his head out from among the leaves, his face brown and scarred, and eyes glistening, as he looked from place to place.

It was all so real that Don expected to see the scoundrel step out into the open, followed by his two companions.

And this did happen a few minutes later. Mike Bannock, armed with a heavy club, and followed by his two brothers in crime, crept out. Then it seemed to be no longer the convicts’ home, and Don started from his dreamy state, horrified at what he saw, for the scoundrels had not seen him, and were going cautiously toward the little settlement, whose occupants were all away hunting, fishing, and attending to their crops. Don alone was close at hand, and he in so semi-delirious and helpless a state, that when he tried to rise he felt as if it would be impossible to warn his friends of their danger, and prevent these ruffians from making their descent upon the pleasant little homes around.

An acute pain across the brows made Don close his eyes, and when he re-opened them his head was throbbing, his mind confused, and as he looked hastily round, and could see nothing but the beautiful verdant scene, he felt that he had been deceived, and as if the figures that had passed out of the dense undergrowth had been merely creatures of his imagination.

He still gazed wildly about, but all was peaceful, and not a sound save the birds’ notes fell upon the ear.

“It must have been fancy,” he thought. “Where is Jem?”

He sank back again in a strangely excited state, for the idea that, in his fleeing to this peaceful place, he had been the means of bringing three desperate men to perhaps rob, and murder, and destroy, where all was repose and peace, was too terrible to bear.

One minute he was certain that it was all fancy, just as he had dreamed again and again of Mike and his ruffianly companions; the next he was as sure that what he had seen was real.

“I’ll go and find some one,” he said hastily; and, rising feebly to his feet, he set off for the farm, but only to catch wildly at the trees to save himself from falling.

The vertigo passed off as quickly as it came on.

“How absurd!” he said, with a faint laugh. “A moment’s giddiness. That’s all.”

He started again, but everything sailed round, and he sank upon the earth with a groan to try and make out whether it was all fancy or a dream.

In a moment he seemed to be back at home with a bad headache, and his mother passing softly to and fro, while Kitty, full of sympathy, kept soaking handkerchiefs in vinegar and water to cool his heated brow.

Then, as he lay with his eyes tightly closed, Uncle Josiah came into the room, and laid his hand pityingly upon his shoulder.

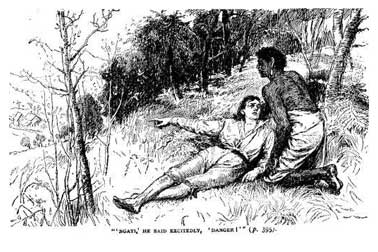

Don gazed up at him, to see that it was Ngati’s hideously tattooed countenance close to his, and he looked up confused and wondering at the great chief.

Then the recollection of the convicts came back, and a spasm of horror shot through his brain.

If it was true, what would happen at the little farm?

He raised himself upon his elbow, and pointed in the direction of the house.

“Ngati,” he said excitedly, “danger!”

The chief looked at him, then in the direction in which he pointed; but he could understand nothing, and Don felt as if he were trying to get some great dog to comprehend his wishes.

He had learned scores of Maori words, but now that he wanted to use them, some would not come, and others would not fit.

“Ngati!” he cried again piteously, as he pointed toward the farm, “pakehas—bad pakehas.”

The chief could understand pakehas—white men, but he was rather hazy about bad, whether it did not mean good, and he gave a low grunt.

“Bad pakehas. Fight. Jem,” panted Don.

Ngati could see that something was wrong, but in his mind it seemed to be connected with his English friend’s health, and he laid his hand upon Don’s burning brow.

“Bad pakehas—go!” cried Don. “What shall I do? How am I to make him understand? Pakehas. Jem. Help!”

At that Ngati seemed to have a glimmering of what his companion meant, and nodding quickly, he went off at a trot toward the farm.

“He’ll bring some one who can understand,” said Don to himself; and then he began to feel that, after all, it was a dream consequent upon his being so ill, and he lay back feeling more at ease, but only to jump up and stare wildly toward where the farm lay.

For, all at once, there rose a shout, and directly after a shot was heard, followed by another and another.

Then all was still for a few minutes, till, as Don lay gazing wildly toward where he had seen Ngati disappear, he caught sight of a stooping figure, then of another and another, hurrying to reach cover; and as he recognised the convicts, he could make out that each man carried a gun.

He was holding himself up by grasping the bough of a tree, and gazing wildly at Mike and his brutal-looking friends; but they were looking in the direction of the farm as they passed, and they did not see him.

Then the agonising pain in his head seemed to rob him of the power to think, and he sank back among the ferns.

Don had some consciousness of hearing voices, and of feeling hands touching him; but it was all during a time of confusion, and when he looked round again with the power to think, he was facing a tiny unglazed window, the shutter which was used to close it standing below.

He was lying on a rough bed formed of sacking spread over dried fern leaves, and the shed he was in had for furniture a rough table formed by nailing a couple of pieces of board across a tub, another tub with part of the side sawn out formed an armchair; and the walls were ornamented with bunches of seeds tied up and hung there for preservation, a saddle and bridle, and some garden tools neatly arranged in a corner.

Don lay wondering what it all meant, his eyes resting longest upon the open window, through which he could see the glorious sunshine, and the leaves moving in the gentle breeze.

He felt very happy and comfortable, but when he tried to raise his head the effort was in vain, and this set him wondering again, till he closed his eyes and lay thinking.

Suddenly he unclosed them again to lie listening, feeling the while that he had been asleep, for close beside him there was some one whistling in a very low tone—quite a whisper of a whistle—a familiar old Somersetshire melody, which seemed to carry him back to the sugar yard at Bristol, where he had heard Jem whistle that tune a score of times.

This set him thinking of home, his mother, and Cousin Kitty. Then of stern-looking Uncle Josiah, who, after all, did not seem to have been unkind.

“Poor Mas’ Don! Will he ever get well again?” a voice whispered close to his ear.

“Jem!”

“Oh, Mas’ Don! Oh! Oh! Oh! Thank the great Lord o’ mussy. Amen! Amen! Amen!”

There was the sound of some one going down heavily upon his knees, a pair of clasped hands rested on Don’s breast; and, as he turned his eyes sidewise, he could see the top of Jem’s head as the bed shook, and there was the sound of some one sobbing violently, but in a choking, smothered way.

“Jem! Is that you? What’s the matter?” whispered Don feebly.

“And he says, ‘What’s the matter?’” cried Jem, raising his head, and bending over Don. “Dear lad, dear lad; how are you now?”

“Quite well, thank you, Jem, only I can’t lift up my head.”

“And don’t you try, Mas’ Don. Oh, the Lord be thanked! The Lord be thanked!” he muttered. “What should I ha’ done?”

“Have—have I been ill, Jem?”

“I’ll, Mas’ Don? Why, I thought you was going to die, and no doctor, not even a drop of salts and senny to save your life.”

“Oh, nonsense, Jem! I never thought of doing such a thing! Ah, I remember now. I felt poorly. My head was bad.”

“Your head bad? I should think it was bad. Dear lad, what stuff you have been saying.”

“Have I, Jem? What, since I lay down among the ferns this morning?”

“This morning, Mas’ Don! Why, it’s close upon a month ago.”

“What?”

“That’s so, my lad. We come back from cutting wood to find you lying under a tree, and when we got here it was to find poor old ‘my pakeha’ with a shot-hole in him, and his head all beaten about with big clubs.”

“Oh, Jem!”

“That’s so, Mas’ Don.”

“Is he better?”

“Oh, yes; he’s getting better. I don’t think you could kill him. Sort o’ chap that if you cut him to pieces some bit or another would be sure to grow again.”

“Why, it was Mike Bannock and those wretches, Jem.”

“That’s what we thought, my lad, but we couldn’t find out. It was some one, and whoever it was took away three guns.”

“I saw them, Jem.”

“You see ’em?”

“Yes, as I lay back with my head so bad that I couldn’t be sure.”

“Ah, well, they found us out, and they’ve got their guns again; but they give it to poor Ngati awful.”

Just then the window was darkened by a hideous-looking face, which disappeared directly. Then steps were heard, and the great chief came in, bending low to avoid striking his head against the roof till he reached the rough bedside, where he bent over Don, and patted him gently, saying softly, “My pakeha.”