Chapter 41 | Prisoners of War | The Adventures of Don Lavington

“I wish our old ship was here, and I was at one of the guns to help give these beggars a broadside.”

“It is very, very horrible, Jem.”

“Ten times as horrid as that, Mas’ Don. Here was we all as quiet and comf’table as could be—taking our warm baths. I say, shouldn’t I like one now! I’m that stiff and sore I can hardly move.”

“Yes, it would be a comfort, Jem.”

“Yes, and as I was saying, here was we going on as quiet as could be, and interfering with nobody, when these warmints came; and look at things now.”

“Yes,” said Don, sadly, as he looked round; “half the men dead, the others wounded and prisoners, with the women and children.”

“And the village—I s’pose they calls this a village; I don’t, for there arn’t no church—all racked and ruined.”

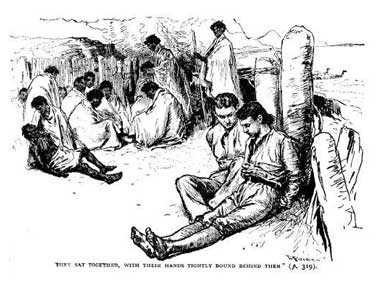

They sat together, with their hands tightly bound behind them, gazing at the desolation. The prisoners were all huddled together, perfectly silent, and with a dull, sullen, despairing look in their countenances, which seemed to suggest that they were accepting their fate as a matter of course.

It was a horrible scene, so many of the warriors being badly wounded, but they made no complaint; and, truth to tell, most of those who were now helpless prisoners had taken part in raids to inflict the pain they now suffered themselves.

The dead had been dragged away before Don woke that morning, but there were hideous traces on the trampled ground, with broken weapons scattered here and there, while the wounded were lying together perfectly untended, many of them bound, to prevent escape—hardly possible even to an uninjured man, for a guard was keeping watch over them ready to advance threateningly, spear in hand, if a prisoner attempted to move.

Where Don and Jem were sitting a portion of the great fence was broken, and they could see through it down to the shore.

“What a shame it seems on such a glorious morning, Jem!”

“Shame! Mas’ Don? I should just like to shame ’em. Head hurt much?”

“Not so very much, Jem. How is your shoulder?”

“Rather pickly.”

“Rather what?”

“Pickly, as if there was vinegar and pepper and salt being rubbed into it. But my old mother used to say that it was a good sign when a cut smarted a lot. So I s’pose my wound’s first rate, for it smarts like a furze bush in a fit.”

“I wish I could bathe it for you, Jem.”

“Thank ye, Mas’ Don. I wish my Sally could do it. More in her way.”

“We must try and bear it all, I suppose, Jem. How hot the sun is; and, ill as I am, I should be so glad of something to eat and drink.”

“I’m that hungry, Mas’ Don,” growled Jem, “that I could eat one o’ these here savages. Not all at once, of course.”

“Look, Jem. What are they doing there?”

Don nodded his head in the direction of the broken fence; and together they looked down from the eminence on which the pah was formed, right upon the black volcanic sand, over which the sea ran foaming like so much glistening silver.

There were about fifty of the enemy busy there running to and fro, and the spectators were not long left in doubt as to what they were doing, for amid a great deal of shouting one of the huge war canoes was run down over the sand and launched, a couple of men being left to keep her by the shore, while their comrades busied themselves in launching others, till every canoe belonging to the conquered tribe was in the water.

“That’s it, is it?” said Jem. “They came over land, and now they’re going back by water. Well, I s’pose, they’ll do as they like.”

“Isn’t this nearest one Ngati’s canoe, Jem?”

“Yes, my lad; that’s she. I know her by that handsome face cut in the front. I s’pose poor Ngati’s dead.”

“I’m afraid so,” said Don, sadly. “I’ve been trying to make out his face and Tomati’s among the prisoners, but I can’t see either.”

“More can’t I, Mas’ Don. It’s a werry bad job. Lookye yonder now.”

Don was already looking, for a great deal of excited business was going on below, where the victorious tribe was at work, going and coming, and bringing down loads of plunder taken from the various huts. One man bore a bundle of spears, another some stone tomahawks, which were rattled into the bottom of the canoes. Then paddles, and bundles of hempen garments were carried down, with other objects of value in the savage eye.

This went on for hours amidst a great deal of shouting and laughter, till a large amount of spoil was loaded into the canoes, one being filled up and deep in the water.

Then there seemed to be a pause, the canoes being secured to trees growing close down to the shore, and the party busy there a short time before absent.

“Coming to fetch us now, I suppose, Mas’ Don,” said Jem. “Wonder whether they’ve got your pistol and cutlash.”

But no one but the guards came in sight, and a couple of weary hours passed, during which the other prisoners sat crouched together, talking in a low tone, apparently quite indifferent to their fate; and this indifference seemed so great that some of the thoughtless children began to laugh and talk aloud.

For some time this was passed over unnoticed; but at last one of the guards, a tall Maori, whose face was so lined in curves that it seemed to be absolutely blue, walked slowly over to the merry group, spear in hand, to give one child a poke with the butt, another a sharp blow over the head, evidently with the intention of producing silence; but in the case of the younger children his movements had the opposite effect, and this roused the ire of some of the women, who spoke out angrily enough to make the tall, blue-faced savage give a threatening gesture with his spear.

Just at that moment, however, a loud shouting and singing arose, which took the man’s attention, and he and his fellows mounted on a stage at one corner of the pah to stand leaning upon their spears, gazing down at the festivities being carried on at the edge of the sands below.

For some time past it had seemed to Don that the plundering party had fired the village, for a tall column of smoke had risen up, and this had died down and risen again as combustible matter had caught.

The fire was too far below to be seen, but the smoke rose in clouds as the work of destruction seemed to be going on.

The singing and shouting increased, and once or twice the other prisoners appeared to take an excited interest in the sounds that came up to them; but they only sank directly after into a state of moody apathy, letting their chins go down upon their chests, and many of them dropping off to sleep.

The noise and shouting had been going on for some time, and then ceased, to be succeeded by a low, busy murmur, as of a vast swarm of bees; and now, after sitting very silent and thoughtful, watching the faint smoke which came up from the fire, and eagerly drinking in the various sounds, Don turned his eyes in a curiously furtive manner to steal a look at Jem.

He did not move his head, but proceeded with the greatest caution, so as to try and read his companion’s countenance, when, to his surprise, he found that Jem was stealing a look at him, and both, as it were, snatched their eyes away, and began looking at the prisoners.

But at that time it was as if the eyes of both were filled with some strange attractive force, which made them turn and gaze in a peculiarly hard, wild way.

Don seemed to be reading Jem’s thoughts as his sight plunged deeply into the eyes of his companion, and as he gazed, he shuddered, and tried to look elsewhere.

But he could not look elsewhere, only hard at Jem, who also shuddered, and looked shame-faced and horrified.

For they were reading each other’s thoughts only too correctly, and the effect of that perusal was to make big drops of perspiration roll down Jem’s face, and to turn Don deadly pale.

At last each snatched his eyes away, Jem to watch the prisoners, Don to close his, and sit trembling and listening to the bursts of merriment which came up.

At such times, in spite of their efforts, they could not imitate the apathy of the New Zealanders, but gazed wildly at each other, trying to make themselves believe that what they imagined was false, or else the prisoners would have shown some sign of excitement.

At last Jem ceased to make any pretence about the matter. He stared speechlessly and full of misery at Don, who let his eyes rest wildly on Jem’s for a time before dropping his head upon his chest, and sitting motionless.

All through the rest of that hour, and hour after hour, till towards evening, did the wretched prisoners sit in despair and misery without food or water; and the sounds of merriment and feasting came loudly to where they were.

The sun was descending rapidly when about half-a-dozen of the conquering tribe came up to the pah, with the result that those who were on guard suddenly grew wildly excited, and giving up their duties to the new comers, uttered eager shouts and rushed off in a way that was frantic in the extreme.

Don and Jem again exchanged looks full of misery and despair, and then gazed with wonder and loathing at the new comers, who walked slowly about for a few minutes, and then went and leaned their backs against the palisading of the pah, and partially supported themselves upon their spears.

“Ugh!” ejaculated Jem with a shudder as he turned away. “You wretches! Mas’ Don, I felt as I lay here last night, all dull and miserable and sick, and hardly able to bear myself—I felt so miserable because I knew I must have shot some of those chaps.”

“So did I, Jem,” sighed Don; “so did I.”

“Well, just now, Mas’ Don, I’m just ’tother way; ay, for I wish with all my heart I’d shot the lot. Hark, there!”

They listened, and could hear a burst of shouting and laughing.

“That’s them sentries gone down now to the feast. I say, Mas’ Don, look at these here fellows.”

“Yes, Jem, I’ve been looking at them. It’s horrible, and we must escape.”

They sat gazing at their guards again, to see that they were flushed, their eyes full, heavy, and starting, and that they were absolutely stupefied and torpid as some huge serpent which has finished a meal.

“They must be all drunk, Jem,” whispered Don, with a fresh shudder of horror and loathing.

“No, Mas’ Don, ’tarn’t that,” said Jem, with a look of disgust. “Old Mike used to tell us stories, and most of ’em was yarns as I didn’t believe; but he told us one thing as I do believe now. He said as some of the blacks in Africa would go with the hunters who killed the hippipperpothy-mouses, and when they’d killed one, they’d light a fire, and then cut off long strips of the big beast, hold ’em in the flame for a bit, and then eat ’em, and cut off more strips and eat them, and go on eating all day till they could hardly see or move.”

“Yes, I remember, Jem; and he said the men ate till they were drunk; and you said it was all nonsense, for a man couldn’t get drunk without drink.”

“Yes, Mas’ Don; but I was all wrong, and Mike was right. Those wretches there are as much like Mike Bannock was when he bored a hole in the rum puncheon as can be. Eating too much makes people as stupid as drinking; and knowing what I do, I wishes I was in Africa and not here.”

“Knowing what you do, Jem?”

“Yes, Mas’ Don, knowing what I do. It’s what you know too. I can see you do.”

Don shuddered.

“Don’t, Jem, don’t; it’s too horrid even to think about.”

“Yes, dear lad, but we must think about it. These here people’s used to it, and done it theirselves, I daresay; and they don’t seem to mind; but we do. Ah, Mas’ Don, I’d rather ha’ been a sailor all my life, or been had by the sharks when we was swimming ashore; for I feel as if I can’t stand this. There, listen!”

There was a sound of shouting and singing from the beach below, and one of the guards tossed up his spear in a sleepy way, and shouted too, but only to subside again into a sluggish state of torpidity.

“Why, Mas’ Don, by-and-by they’ll all be asleep, and if we tried, you and me might get our arms and legs undone, and take a spear apiece, and kill the lot. What do you say?”

“The same as you will, if you think, Jem,” replied Don. “No.”

“No, it is, Mas’ Don, of course. Englishmen couldn’t do such a thing as that.”

“But only let us have a fair chance at them again, Jem, and I don’t think we shall feel very sorry if we slay a few.”

“Sorry?” said Jem, between his teeth. “I mean a hundred of ’em at least, as soon as we can get away; and get away we will.”

They sat listening till the horrible feast below was at an end, and everything became so silent that they concluded that the enemy must be asleep, and began to wonder that the prisoners should all crouch together in so apathetic a state. But all at once, when everything seemed most still, and half the prisoners were dozing, there came the heavy trampling of feet; the guards roused up, and in the dim light of the late evening, the bonds which secured the captives’ feet were loosened, and, like a herd of cattle, they were driven down from the platform upon which the pah was constructed, and along the slope to the sands, where the canoes rode lightly on the swell.

Into these they were forced to climb, some getting in with alacrity, others slowly and painfully; two or three falling helplessly in the water, and then, half drowned, being dragged in over the side.

“Not a bit sorry I killed some of ’em,” muttered Jem. “They arn’t men, Mas’ Don, but savage beasts.”

It did not take long, for there was plenty of room in the little fleet of canoes. The prisoners were divided, some being placed in the canoes with the plunder, and treated as if they were spoil. Others were divided among the long canoes, manned by the enemy, whose own wounded men, even to the worst, did not hesitate to take to a paddle, and fill their places. Some of the children whimpered, but an apathetic state of misery and dejection seemed to have affected even them, while in one or two cases, a blow from a paddle was sufficient to awe the poor little unfortunates into silence.

As soon as the last man was in his place, a herculean chief waved his hands; one of his followers raised a great wooden trumpet, and blew a long, bellowing note; the paddles dipped almost as one into the water, and the men burst into a triumphal chorus, as, for a few hundred yards, the great war canoes which they had captured swept with their freight of spoil at a rapid rate southward along the shore.

Then the sudden burst of energy ceased, the song broke off, the speed diminished; and the men slowly dipped their paddles in a heavy, drowsy way. Every now and then one of the warriors ceased paddling, or contented himself with going through the motion; but still the great serpent-like vessels glided on, though slowly, while the darkness came on rapidly, and the water flashed as its phosphorescent inhabitants were disturbed.

The darkness grew intense, but not for long. Soon a gradual lightening became visible in the east, and suddenly a flash of light glanced along the surface of the sea, as the moon slowly rose to give a weird aspect to the long row of dusky warriors sluggishly urging the great canoes onward.

Don and Jem had the good fortune to be together in the largest and leading canoe; and as they sat there in silence, the strangeness of the scene appeared awful. The shore looked almost black, save where the moon illumined the mountainous background; but the sea seemed to have been turned into a pale greenish metal, flowing easily in a molten state. No one spoke, not a sigh was heard from the prisoners, who must have been suffering keenly as they cowered down in the boat.

Don sat watching the weird panorama as they went along, asking himself at times if it was all real, or only the effect of some vivid dream. For it appeared to be impossible that he could have gone through what he had on the previous night, and be there now, borne who could say whither, by the successful raiders, who were moving their oars mechanically as the canoe glided on.

“It must be a dream,” he said to himself. “I shall awake soon, and—”

“What a chance, Mas’ Don!” said a low voice at his side, to prove to him that he was awake.

“Chance? What chance?” said Don, starting.

“I don’t mean to get away, but for any other tribe to give it to them, and serve ’em as they served our poor friends; for they was friends to us, Mas’ Don.”

“I wish the wretches could be punished,” said Don sadly; “but I see no chance of that.”

“Ah! Wait a bit, my lad; you don’t know. But what a chance it would be with them all in this state. If it wasn’t that I don’t care about being drowned, I should like to set to work with my pocket knife, and make a hole in the bottom of the canoe.”

“It would drown the innocent and the guilty, Jem.”

“Ay, that’s so, my lad. I say, Mas’ Don, arn’t you hungry?”

“Yes, I suppose so, Jem. Not hungry; but I feel as if I have had no food. I am too miserable to be hungry.”

“So am I sometimes when my shoulder burns; at other times I feel as if I could eat wood.”

They sat in silence as the moon rose higher, and the long lines of paddles in the different boats looked more weird and strange, while in the distance a mountain top that stood above the long black line of trees flashed in the moonlight as if emitting silver fire.

“Wonder where they’ll take us?” said Jem, at last.

“To their pah, I suppose,” replied Don, dreamily.

“I s’pose they’ll give us something to eat when we get there, eh?”

“I suppose so, Jem. I don’t know, and I feel too miserable even to try and think.”

“Ah,” said Jem; “that’s how those poor women and the wounded prisoners feel, Mas’ Don; but they’re only copper-coloured blacks, and we’re whites. We can’t afford to feel as they do. Look here, my lad, how soon do you think you’ll be strong enough to try and escape?”

“I don’t know, Jem.”

“I say to-morrow.”

“Shall you be fit?”

Jem was silent for a few minutes.

“I’m like you, Mas’ Don,” he said. “I dunno; but I tell you what, we will not say to-morrow or next day, but make up our minds to go first chance. What do you say to that?”

“Anything is better than being in the power of such wretches as these, Jem; so let’s do as you say.”

Jem nodded his head as he sat in the bottom of the canoe in the broad moonlight, and Don watched the soft silver sea, the black velvet-looking shore, and the brilliant stars; and then, just as in his faintness, hunger, and misery, he had determined in his own mind that he would be obliged to sit there and suffer the long night through, and began wondering how long it would be before morning, he became aware of the fact that Nature is bounteously good to those who suffer, for he saw that Jem kept on nodding his head, as if in acquiescence with that which he had said; and then he seemed to subside slowly with his brow against the side.

“He’s asleep!” said Don to himself. “Poor Jem! He always could go to sleep directly.”

This turned Don’s thoughts to the times when, after a hard morning’s work, and a hasty dinner, he had seen Jem sit down in a corner with his back against a tub, and drop off apparently in an instant.

“I wish I could go to sleep and forget all this,” Don said to himself with a sigh—“all this horror and weariness and misery.”

He shook his head: it was impossible; and he looked again at the dark shore that they were passing, at the shimmering sea, and then at the bronzed backs of the warriors as they paddled on in their drowsy, mechanical way.

The movement looked more and more strange as he gazed. The men’s bodies swayed very little, and their arms all along the line looked misty, and seemed to stretch right away into infinity, so far away was the last rower from the prow. The water flashed with the moonlight on one side, and gleamed pallidly on the other as the blades stirred it; and then they grew more misty and more misty, but kept on plash—plash—plash, and the paddles of the line of canoes behind echoed the sound, or seemed to, as they beat the water, and Jem whispered softly in his ear,—

“Don’t move, Mas’ Don, my lad, I’m not tired!”

But he did move, for he started up from where his head had been lying on Jem’s knees, and the poor fellow smiled at him in the broad morning sunshine. Sunshine, and not moonshine; and Don stared. “Why, Jem,” he said, “have I been asleep?”

“S’pose so, Mas’ Don. I know I have, and when I woke a bit ago, you’d got your head in my lap, and you was smiling just as if you was enjoying your bit of rest.”