Chapter 11 | Thinking Better Of It | The Adventures of Don Lavington

Don stood looking at Jem Wimble for some few minutes in silence, as if the sight of some one else in trouble did him good. Then he sat down on the stock of an old anchor, to begin picking at the red rust scales as he too stared at the ships moored here and there.

The tall masts and rigging had a certain fascination for Don, and each vessel seemed to offer a way out of his difficulties. For once on board a ship with the sails spread, and the open sea before him, he might cross right away to one of those beautiful lands of which Mike had spoken, and then—

The thought of Mike altered the case directly, and he sat staring straight before him at the ships.

Jem was the next to break the silence.

“Thinking you’d like to go right away, Master Don?”

“Yes, Jem.”

“So was I, sir. Only think how nice it would be somewhere abroad, where there was no Sally.”

“And no Uncle Josiah, Jem.”

“Ay, and no Mike to get you into trouble. Be fine, wouldn’t it?”

“Glorious, Jem.”

“Mean to go, Master Don?”

“What, and be a miserable coward? No.”

“But you was a-thinking something of the kind, sir.”

“Yes, I was, Jem. Everybody is stupid sometimes, and I was stupid then. No. I’ve thought better of it.”

“And you won’t go, sir?”

“Go? No. Why, it would be like saying what Mike accused me of was true.”

“So it would, sir. Now that’s just how I felt. I says to myself, ‘Jem,’ I says, ‘don’t you stand it. What you’ve got to do is to go right away and let Sally shift for herself; then she’d find out your vally,’ I says, ‘and be sorry for what she’s said and done,’ but I knew if I did she’d begin to crow and think she’d beat me, and besides, it would be such a miserable cowardly trick. No, Mas’ Don, I’m going to grin and bear it, and some day she’ll come round and be as nice as she’s nasty now.”

“Yes, that’s the way to look at it, Jem; but it’s a miserable world, isn’t it?”

“Well, I arn’t seen much on it, Mas’ Don. I once went for a holiday as far as Bath, and that part on it was miserable enough. My word, how it did rain! In half an hour I hadn’t got a dry thread on me. Deal worse than Bristol, which isn’t the most cheersome o’ places when you’re dull.”

“No, Jem, it isn’t. Of course you’ll be at the court to-morrow?”

“I suppose so, Mas’ Don. And I say they’d better ask me if I think you took that money. My! But I would give it to some on ’em straight. Can you fight, Mas’ Don?”

“I don’t know, Jem. I never tried.”

“I can. You don’t know what a crack I could give a man. It’s my arms is so strong with moving sugar-hogsheads, I suppose. I shouldn’t wish to be the man I hit if I did my best.”

“You mean your worst, Jem.”

“Course I do, Mas’ Don. Well, as I was going to say, I should just like to settle that there matter with Mr Mike without the magistrates. You give him to me on a clear field for about ten minutes, and I’d make Master Mike down hisself on his knees, and say just whatever I pleased.”

“And what good would that do, Jem?”

“Not much to him, Mas’ Don, because he’d be so precious sore afterwards, but it would do me good, and I would feel afterwards what I don’t feel now, and that’s cheerful. Never mind, sir, it’ll all come right in the end. Nothing like coming out and sitting all alone when you’re crabby. Wind seems to blow it away. When you’ve been sitting here a bit you’ll feel like a new man. Mind me smoking a pipe?”

“No, Jem; smoke away.”

“Won’t have one too, Mas’ Don?”

“No, Jem; you know I can’t smoke.”

“Then here goes for mine,” said Jem, taking a little dumpy clay pipe from one pocket and a canvas bag from another, in which were some rough pieces of tobacco leaf. These he crumbled up and thrust into the bowl, after which he took advantage of the shelter afforded by an empty cask to get in, strike a light, and start a pipe.

Once lit up, Jem returned to his old seat, and the pair remained in the same place till it was getting dusk, and lights were twinkling among the shipping, when Jem rose and stretched himself.

“That’s your sort, Mas’ Don,” he said. “Now I feels better, and I can smile at my little woman when I get home. You aren’t no worse?”

“No, Jem, I am no worse.”

“Nothing like coming out when you’re red hot, and cooling down. I’m cooled down, and so are you. Come along.”

Don felt a sensation of reluctance to return home, but it was getting late, and telling himself that he had nothing to do now but act a straightforward manly part, and glad that he had cast aside his foolish notions about going away, he trudged slowly back with his companion, till turning into one of the dark and narrow lanes leading from the water side, they suddenly became aware that they were not alone, for a stoutly-built sailor stepped in front of them.

“Got a light, mate?” he said.

“Light? Yes,” said Jem readily; and he prepared to get out his flint and steel, when Don whispered something in his ear.

“Ay, to be sure,” he said; “why don’t you take a light from him?”

“Eh? Ah, to be sure,” said the sailor. “I forgot. Here, Joe, mate, open the lanthorn and give us a light.”

Another sailor, a couple of yards away, opened a horn lanthorn, and the first man bent down to light his pipe, the dull rays of the coarse candle showing something which startled Don.

“Come on, Jem,” he whispered; “make haste.”

“Ay? To be sure, my lad. There’s nothing to mind though. Only sailors.”

As he spoke there were other steps behind, and more from the front, and Don realised that they were hemmed in that narrow lane between two little parties of armed men.

Just then the door of the lanthorn was closed, and the man who bore it held it close to Jem’s face.

“Well?” said that worthy, good-temperedly, “what d’yer think of me, eh? Lost some one? ’Cause I arn’t him.”

“I don’t know so much about that,” said a voice; and a young-looking man in a heavy pea jacket whispered a few words to one of the sailors.

Don felt more uneasy, for he saw that the point of a scabbard hung down below the last speaker’s jacket, which bulged out as if there were pistols beneath, all of which he could dimly make out in the faint glow of the lanthorn.

“Come away, Jem, quick!” whispered Don.

“Here, what’s your hurry, my lads?” said the youngish man in rather an authoritative way. “Come and have a glass of grog.”

“No, thank ye,” said Jem; “I’ve got to be home.”

“So have we, mate,” said the hoarse-voiced man who had asked for a light; “and when a horficer asks you to drink you shouldn’t say no.”

“I knew it, Jem,” whispered Don excitedly. “Officer! Do you hear?”

“What are you whispering about, youngster?” said the man in the pea jacket. “You let him be.”

“Good-night,” said Jem shortly. “Come on, Mas’ Don.”

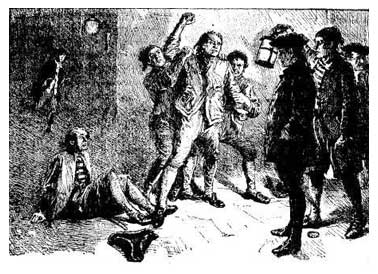

He stepped forward, but the young man hurried on the men, who had now closed in round them; and as Jem gave one of them a sturdy push to get off, the thrust was returned with interest.

“Where are you shovin’ to, mate?” growled the man. “Arn’t the road wide enough for you?”

“Quiet, my lad,” said the officer sharply. “Here, you come below here and have a glass of grog.”

“I don’t want no grog,” said Jem; “and I should thank you to tell your men to let me pass.”

“Yes, by-and-by,” said the officer. “Now then, my lads, sharp.”

A couple of men crowded on Jem, one of them forcing himself between the sturdy fellow and Don, whose cheeks flushed with anger as he felt himself rudely thrust up against the wall of one of the houses.

“Here, what are you doing of?” cried Jem sharply.

“Being civil,” said one of the men with a laugh. “There, no nonsense. Come quiet.”

He might just as well have said that to an angry bull, for as he and his companion seized Jem by the arms, they found for themselves how strong those arms were, one being sent staggering against Don, and the other being lifted off his legs and dropped upon his back.

“Now, Mas’ Don, run!” shouted Jem.

But before the words were well out of his lips, the party closed in upon him, paying no heed to Don, who in accordance with Jem’s command had rushed off in retreat.

A few moments later he stopped, for Jem was not with him, but struggling with all his might in the midst of the knot of men who were trying to hold him.

“Mas’ Don! Help, help!” roared Jem; and Don dashed at the gang, his fists clenched, teeth set, and a curious singing noise in his ears. But as he reached the spot where his companion was making a desperate struggle for his liberty, Jem shouted again,—

“No, no! Mas’ Don; run for it, my lad, and get help if you can.”

Like a flash it occurred to Don that long before he could get help Jem would be overpowered and carried off, and with the natural fighting instinct fully raised, he struck out with all his might as he strove to get to the poor fellow, who was writhing and heaving, and giving his captors a tremendous task to hold him.

“Here, give him something to keep him quiet,” growled a voice.

“No, no; get hold of his hands; that’s right. Serve this cockerel the same. Down with him, quick!” cried the officer sharply; and in obedience to his words the men hung on to poor Jem so tenaciously that he was dragged down on the rough pavement, and a couple of men sat panting upon him while his wrists were secured, and his voice silenced by a great bandage right over his mouth.

“You cowards!” Jem tried to roar, as, breathless with exertion, bleeding from a sharp back-handed blow across the mouth, and giddy with excitement and the effects of a rough encounter between his head and the wall, Don made one more attempt to drag himself free, and then stood panting and mastered by two strong men.

“Show the light,” said the officer, and the lanthorn was held close to Don’s face.

“Well, if the boy can fight like that,” said the officer, “he shall.”

“Let us go,” cried Don. “Help! He—”

A jacket was thrown over his head, as the officer said mockingly,—

“He shall fight for his Majesty the king. Now, my lads, quick. Some one coming, and the wrong sort.”

Don felt himself lifted off his feet, and half smothered by the hot jacket which seemed to keep him from breathing, he was hurried along two or three of the lanes, growing more faint and dizzy every moment, till in the midst of a curious nightmare-like sensation, lights began suddenly to dance before his eyes; then all was darkness, and he knew no more till he seemed to wake up from a curious sensation of sickness, and to be listening to Jem Wimble, who would keep on saying in a stupid, aggravating manner,—“Mas’ Don, are you there?”

The question must have been repeated many times before Don could get rid of the dizzy feeling of confusion and reply,—“Yes; what do you want?”

“Oh, my poor lad!” groaned Jem. “Here, can you come to me and untie this?”

“Jem!”

“Yes.”

“What does it mean? Why is it so dark? Where are we?”

“Don’t ask everything at once, my lad, and I’ll try to tell you.”

“Has the candle gone out, Jem? Are we in the big cellar?”

“Yes, my lad,” groaned Jem, “we’re in a big cellar.”

“Can’t you find the candle?” said Don, with his head humming and the mental confusion on the increase. “There’s a flint and steel on the ledge over the door.”

“Is there, my lad? I didn’t know it,” muttered Jem. “Jem, are you there?”

“Yes, yes, my lad, I’m here.”

“Get a light, quick. I must have fallen and hurt myself; my face bleeds.”

“Oh, my poor dear lad!”

“Eh? What do you mean? You’re playing tricks, Jem, and it’s too bad. Get a light.”

“My hands is tied fast behind me, Mas’ Don,” groaned Jem, “and we’re pitched down here in a cellar.”

“What?”

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear! I don’t mind for myself,” groaned Jem, in his despair, “but what will she do?”

“Jem!”

“I often said I wished I could be took away, but I didn’t mean it, Mas’ Don; I didn’t mean it. What will my Sally do?”

“Jem, are you mad?” shouted Don. “This darkness—this cellar. It’s all black, and I can’t think; my head aches, and it’s all strange. Don’t play tricks. Try and open the door and let’s go.”

“What, don’t you know what it all means, Mas’ Don?” groaned Jem.

“No, I don’t seem as if I could think. What does it mean?”

“Mean, my lad? Why, the press-gang’s got us, and unless we can let ’em know at home, we shall be took aboard ship and sent off to sea.”

“What?”

The light had come—the mental light which drove away the cloud of darkness which had obscured Don Lavington’s brain. He could think now, and he saw once more the dark lane, the swinging lanthorn, and felt, as it were, the struggle going on; and then, sitting up with his hands to his throbbing head, he listened to a low moaning sound close at hand.

“Jem,” he said. “Jem! Why don’t you speak?”

There was no answer, for it was poor Jem’s turn now; the injuries he had received in his desperate struggle for liberty had had their effect, and he lay there insensible to the great trouble which had come upon him, while it grew more terrible to Don, in the darkness of that cellar, with every breath he drew.