Chapter 49 | Unwelcome Acquaintances | The Adventures of Don Lavington

“We shall have to turn and fight, Mas’ Don,” whispered Jem, as they were labouring through the bushes. “They’re close on to us. Here, why don’t Ngati stop?”

There was a faint grey light beginning to steal in among the ferns as they struggled on, keeping up the imitation still, when a shout rose behind, and the Maoris made a rush to overtake them. At that moment from a dark patch of the bush in front three shots were fired in rapid succession.

Don stopped short in the faint grey light, half stunned by the echoing reverberations of the reports which rolled away like thunder, while there was a rushing noise as of people forcing their way in rapid flight through the bush. But he hardly heeded this, his attention being taken up by the way in which Ngati dropped heavily to the ground, and just behind him Jem fell as if struck by some large stone.

A terrible feeling of despair came over Don as, feeling himself between two parties of enemies, he obeyed the natural instinct which prompted him to concealment, and sank down among the ferns.

What should he do? Run for his life, or stay to help his wounded companions, and share their fate?

He stopped and listened to a peculiar sound which he knew was the forcing down of a wad in a gun-barrel. Then the strange hissing noise was continued, and he could tell by the sounds that three guns were being loaded.

The natives, as far as he knew, had no guns, therefore these must be a party of sailors sent to shoot them down; and in the horror of being seen and made the mark for a bullet, Don was about to creep cautiously into a denser part of the bush, when he stopped short, asking himself whether he was in a dream.

“All primed?” cried a hoarse voice, which made Don wonder whether he was back in his uncle’s yard at Bristol.

“Ay, ay.”

“Come on, then. I know I brought one of ’em down. Sha’n’t want no more meat for a month.”

“Say, mate, what are they?”

“I d’know. Noo Zealand turkeys, I s’pose.”

“Who ever heard of turkey eight or nine foot high!” growled one of the approaching party.

“Never mind who heard of ’em; we’ve seen ’em and shot ’em. Hallo! Where are they? Mine ought to be about here.”

“More to the left, warn’t it, mate?”

“Nay, it was just about here.”

There was a loud rustling and heavy breathing as if men were searching here and there, and then some one spoke again—the man whose voice had startled Don.

“I say, lads, you saw me bring that big one down?”

“I saw you shoot at it, Mikey; but it don’t seem as if you had brought it down. They must ha’ ducked their heads, and gone off under the bushes.”

“But they was too big for that.”

“Nay, not they. Looked big in the mist, same as things allus do in a fog.”

“I don’t care; I see that great bird quite plain, and I’m sure I hit him, and he fell somewhere—hah!”

There was the sharp click, click of a gun being cocked, and a voice roared out,—

“Here, you, Mike Bannock, don’t shoot me.”

There was a loud rustling among the ferns, and then Jem shouted again.

“Mas’ Don—Ngati! Why—hoi—oh! It’s all right!”

The familiar voice—the name Mike Bannock, and Jem’s cheery, boyish call, made Don rise, wondering more than ever whether this was not a dream.

The day was rapidly growing lighter, and after answering Jem’s hail, Don caught sight of him standing under a tree in company with three wild, gaunt-looking men.

“Mas’ Don! Ahoy! Mas’ Don!”

“I’m here, Jem, but mind the Maoris.”

“I forgot them!” cried Jem. “Look out! There was a lot of savages arter us.”

The three men darted behind trees, and stood with their guns presented in the direction of the supposed danger, Don and Jem also seeking cover and listening intently.

“Were you hit, Jem?”

“No, my lad; were you?”

“No. Where’s Ngati?”

“I’m afraid he has got it, my lad. He went down like a stone.”

“But Mike! How came he here?”

“I d’know, my lad. Hi! Stop! Don’t shoot. Friends.”

Ngati, who came stalking up through the bush, spear in hand, had a narrow escape, for two guns were presented at him, and but for the energetic action of Don and Jem in striking them up, he must have been hit.

“Oh, this is a friend, is it?” said Mike Bannock, as he gave a tug at his rough beard, and turned from one to the other. “Arn’t come arter me, then?”

“No, not likely,” said Jem. “Had enough of you at home.”

“Don’t you be sarcy,” growled Mike Bannock; “and lookye here, these gentlemen—friends of mine!”—he nodded sidewise at the two fierce-looking desperadoes at his side—“is very nice in their way, but they won’t stand no fooling. Lookye here. How was it you come?”

“In a ship of war,” said Don.

“Ho! Then where’s that ship o’ war now?”

“I don’t know.”

“No lies now,” said the fellow fiercely; “one o’ these here gentlemen knocked a man on the head once for telling lies.”

“Ah,” growled one of the party, a short, evil-looking scoundrel, with a scar under his right eye.

“Hear that?” cried Mike Bannock. “Now, then, where’s that there ship?”

“I tell you I don’t know,” said Don sharply.

“Whorrt!” shouted Mike, seizing Don by the throat; but the next moment a sharp blow from a spear handle made him loosen his hold, and Ngati stood between them, tall and threatening.

“Here, come on, mates, if you don’t want to be took!” cried Mike, and his two companions raised the rusty old muskets they bore.

“Put them down, will yer?” cried Jem. “Lookye here, Mike Bannock: Mas’ Don told you he didn’t know where the ship was, and he don’t. We’ve left her.”

“Ah!” growled Mike, looking at him suspiciously. “Now, look here: don’t you try none of your games on me.”

“Look here!” cried Jem fiercely; “if you give me any of your impudence, Mike Bannock, I’ll kick you out of the yard.”

“Haw-haw!” laughed Mike. “This here arn’t Bristol, little Jemmy Wimble, and I’m a free gen’leman now.”

“Yes, you look it,” said Don, contemptuously. “You scoundrel! How did you come here?”

“Don’t call names, Mr Don Lavington, sir,” whined the ruffian. “How did I come here? Why, me and these here friends o’ mine are gentlemen on our travels. Arn’t us, mates.”

“Ay: gen’lemen on our travels,” said the more evil-looking of the pair; “and look here, youngster, if you meets any one who asks after us, and whether you’ve seen us, mind you arn’t. Understand?”

Don looked at him contemptuously, and half turned away.

“Who was there after you?” said Mike Bannock, suspiciously.

“Some of a tribe of Maoris,” replied Jem.

“No one else?”

“No.”

“Ah, well, we arn’t afeared of them.” He patted the stock of his gun meaningly. “Soon make a tribe of them run home to their mothers. See them big birds as we shot at? And I say, young Lavington, what have you been doing to your face? Smudging it to keep off the flies?”

Don coloured through the grey mud, and involuntarily clapped his hand to his face, for he had forgotten the rough disguise.

“Never you mind about his face,” said Jem grinning. “What birds?”

“Them great birds as we shot at,” said Mike. “I brought one of ’em down.”

“You! You couldn’t hit a haystack,” said Jem. “You hit no bird.”

“Ask my mates!” cried Mike eagerly. “Here you, Don Lavington, you usen’t to believe me when I told you ’bout big wild beasts and furrin lands. We see three birds just here, fourteen foot high.”

“You always were a liar, Mike,” said Don contemptuously. “You did not see any bird fourteen feet high, because there are no such things. You didn’t see any birds at all.”

“Well, of all—” began Mike, but he stopped short as he heard Don’s next words,—

“Come, Jem! Come, Ngati! Let’s get on.”

He stepped forward, but after a quick exchange of glances with his companions, Mike stood in his way.

“No you don’t, young un; you stops along of us.”

“What!” cried Don.

“We’re three English gen’lemen travelling in a foreign country among strangers, and we’ve met you two. So we says, says we, folks here’s a bit too handy with their spears, so it’s as well for Englishmen when they meet to keep together, and that’s what we’re going to do.”

“Indeed, we are not!” cried Don. “You go your way, and we’ll go ours.”

“That’s our way,” said Mike quickly. “Eh, mates?”

“Ay. That’s a true word.”

“Then we’ll go the way you came,” cried Don.

“Nay, you don’t; that’s our way, too.”

“The country’s open, and we shall go which way we like,” cried Don.

“Hear, hear, Mas’ Don!” cried Jem.

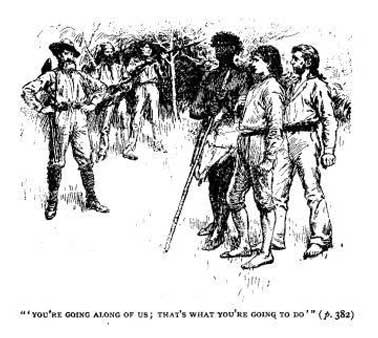

“You hold your tongue, old barrel cooper!” cried Mike. “You’re going along of us; that’s what you’re going to do.”

“That we are not!” cried Don.

“Oh, yes, you are, so no nonsense. We’ve got powder and shot, and you’ve only got spears, and one gun’s equal to fifty spears.”

“Look here, sir!” cried Don sternly, “I don’t want any words with such a man as you. Show me the way you want to take, and we’ll go another.”

“This here’s the way,” said Mike menacingly. “This is the way we’re going, and you’ve got to come with us.”

“Jem; Ngati; come on,” said Don.

“Oh, then you mean to fight, do you?” growled Mike. “Come on then, mates. I think we can give ’em a lesson there.”

“Mas’ Don,” whispered Jem, “it’s no good to fight again guns, and my shoulder’s a reg’lar dummy. Let’s give in civil, and go with them. We’ll get away first chance, and it do make us six again’ any savages who may come.”

“Savages!” said Don angrily; “why, where would you get such savages as these? The Maoris are gentlemen compared to them.”

“That’s my ’pinion again, Mas’ Don; but we’d better get on.”

“But why do they want us with them?”

“Strikes me they’re ’fraid we shall tell on them.”

“Tell on them?”

“Yes; it’s my belief as Master Mike’s been transported, and that he’s contrived to get away with these two.”

“And we are to stop with three such men as these?”

“Well, they arn’t the sort of chaps I should choose, Mas’ Don; but they say they’re gen’lemen, so we must make the best of it. All right, Mike, we’re coming.”

“That’s your sort. Now, then, let’s find my big bird, and then I’m with you.”

“Yah! There’s no big bird,” said Jem. “We was the birds, shamming so as to get away from the savages.”

“Then you may think yourself precious lucky you weren’t shot. Come on.”

Mike led the way, and Don and his companions followed, the two rough followers of Mike Bannock coming behind with their guns cocked.

“Pleasant that, Mas’ Don,” said Jem. “Like being prisoners again. But they can’t shoot.”

“Why did you say that, Jem?” said Don anxiously.

“Because we’re going to make a run for it before long, eh, my pakeha?”

“My pakeha,” said Ngati, laying his hand on Don’s shoulder, and he smiled and looked relieved, for the proceedings during the last half-hour had puzzled him.

Don took the great fellow’s arm, feeling that in the Maori chief he had a true friend, and in this way they followed Mike Bannock round one of the shoulders of the mountain, towards where a jet of steam rose with a shrieking noise high up into the air.