Chapter 7 | The Powder Monkey

It was not long after that Phil was between decks, talking to his new friend, the crippled boy, whose face always expanded into a grin of satisfaction when his nurse appeared.

“Here, I wanted you,” he cried. “I’ve got some news. The doctor told me—”

“Did he say that you might soon try to walk?” cried Phil, eagerly.

“No; he said that my leg was going on well, but I was not to try to use it for a long time yet. He told me that we are going to have a big fight with the French. Isn’t it a bother? For I sha’n’t be able to go to my gun.”

“Jack Jeens said he didn’t think we should have a fight,” replied Phil.

“He doesn’t know anything about it,” said the lame boy, impatiently. “But I say, I shall be obliged to stop below; you might come and stop with me.”

“Jack said I should be sent below if there was a fight, so I will.”

“That’s right,” said the boy, with a sigh of relief. “I didn’t want for you to see it and me stop below.”

Phil looked at him in rather a puzzled way, for he did not know whether he was disappointed or pleased—whether he would like to see the battle or prefer to go below.

But he was not to choose, and a few days later he was quite forgotten in the excitement of the great incident. For he had been trained to certain duties in connection with one of the guns, and when the orders were given for the different crews to take their places, he ran to his naturally enough, perfectly ignorant of the fact that the British Fleet was in “Trafalgar’s Bay,” with the Frenchmen before them, while the British sailors, wild with excitement, were eagerly awaiting the orders that should set hundreds of guns bellowing like thunder as they poured their broadsides of shot into the enemy’s sides.

All that little Phil knew was that his ears were deafened by the roar, his throat throbbing and suffering from the dense clouds of smoke which darkened the sky, and that he could hardly see Jack Jeens, who, like the rest of the crew, was stripped to the waist, as he helped to load their gun, which grew hotter and hotter, and finally leapt from the deck at every discharge.

He could only see dimly for the sulphurous mist before his eyes, but there was was Jack Jeens close at hand, always watching him anxiously and ready to make a sign to him from time to time—a sign which meant “More powder,” and sent him running to the hatch-way and down to the magazine, from which he soon returned, heedless of the fact that if he stopped near a patch of burning tinder or wood the bag of flannel which he carried might explode in his hand.

It was all wild noise and confusion, in the midst of which Phil, blackened and besmirched by the smoke and powder amongst which he moved, had eyes for nothing but his friend, who divided his time between toiling at the gun to which he was attached and watching his little protégé, trembling for his safety when he had gone towards the opening in the deck through which he had to descend, and only breathing freely again when he saw the boy come panting back with his charge. Like the rest of the crew, Jack Jeens knew nothing of how the battle went. He had his duty to do, and he did it, till all at once, just as he turned his head aside to give Phil a welcoming look through the gloom, he was conscious of the tremendous shock of a sickening blow.

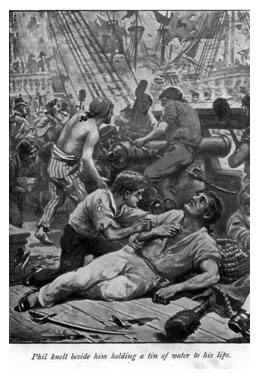

Then all was blank for a time, till the darkness by which he was surrounded opened a little and he found himself lying upon the deck, with Phil looking horrified as he knelt beside him holding a tin of water to his lips.

Poor Jack could not hear what Phil said for the roaring of the guns, but he could read the little fellow’s lips as he pressed him to drink, and sick to the heart and suffering from the terrible wound which had struck him down, he raised his hand to the tin to steady it and drink, but only to see it fall upon the deck, a splinter having struck it from the boy’s hand.

Jack’s wild eyes seemed to say, Are you hurt? But he too made no sound, for at that moment a little group assembled upon the deck, opened out, and both he and Phil saw the figure of their great commander being borne towards them on his way to the spot where he breathed his last. His eyes were open and he was looking wildly round as if in search of something to guide him as to the progress of the great battle, when all at once they rested upon the childlike face of Phil, as the boy knelt beside his wounded and bleeding friend.

A change came over Nelson’s face; the wildly anxious look died out, and as his eyes met those of the boy he smiled at him sadly, and Phil rose quickly to his feet, carried away by the childlike feeling of pity for the dying hero.

It was almost momentary. Then the little group closed in again and passed along the deck, while with the horror and confusion increasing once more, Phil found himself following Jack Jeens, who was being carried below to where the surgeon and his helpmates were busy over their terrible task, and all that the powder monkey saw more of the Battle of Trafalgar was a dim lanthorn swinging by a hammock in which lay poor Jack Jeens, badly  wounded, but with energy enough left to smile at his nurse, who was watching by his side.

wounded, but with energy enough left to smile at his nurse, who was watching by his side.

It was the next morning when, after a stupor-like sleep, Jack opened his eyes, which brightened a little as he saw who was still with him.

“Are you better, Jack?” whispered Phil, anxiously.

“Lots, boy,” was the reply; “only I want to know. Tell me—who won? No, don’t, if it was the French.”

“No, it wasn’t them,” was the quick reply. “We beat, and everyone says it is a great—great—yes, victory—that’s it.”

“Hoo-roar!” came in a faint whisper from Jack Jeens’ lips, and a smile of thankfulness lit up his face for a few moments.

But for a few moments only, for like a shadow came the recollection of something he had seen before he had fainted away from loss of blood.

He lay for a while gazing at Phil as if afraid to speak. Then summoning up his courage he whispered:

“Phil, boy, when I was shot down and you held the water for me to drink, did I dream something?”

Phil gazed back in his eyes, but did not speak, for he with the recollection fresh upon him knew what his poor messmate meant.

And so they rested for a few moments looking in each other’s eyes, till Jack’s slowly closed, and he uttered a low groan.

“I hoped it was a dream,” he said, “and all fancy. But tell me now, Phil, boy; is it true?”

“Yes,” said the little fellow, softly, and there was a choking sound in his fresh young voice as he whispered the words in the wounded sailor’s ear: “Yes; Lord Nelson is dead.”