Chapter 1 | The Powder Monkey

“Hi-lo!”

The little boy raised his head with a sudden start.

“Hilli—hi—ho! What cheer?”

The little fellow started to his feet from where he had been sitting upon a sloping bank, and caught at the bars of the gate close by. He said nothing, but stared through the gloom of the autumn evening at the strange man, who now roared out:

“What cheer, I says! What cheer?”

The little fellow made an effort to speak, but only sighed at first, before stammering out:

“Please, sir, I don’t know what you mean.”

“You don’t?” growled the man, fiercely, as he clapped the palm of his left hand upon the front of his waistband, and the back of his right hand level with it behind; then kicking out his right leg behind, he made a kind of hop on his left, as if to shake himself down into his clothes, as he hoisted them up.

“You don’t?” he said again, as he stared at the little fellow. “What are you, then? A furrener?”

“No, sir,” said the little boy, shrinking; for the man now took a step forward and clapped a big, brown, tarry hand upon his shoulder.

“Then why can’t yer understand yer own lingo?”

“I do, sir,” said the boy, with a sound like a sob.

“Then why did you say you didn’t, and make me think you was a Frenchy?”

“I didn’t know what you meant, sir, by ‘hilli’ something, and ‘what cheer.’”

“Why, yer young savage!” cried the man. “Arn’t yer never been to school?”

“Yes, sir, and had a tutor.”

“A tutor, eh? What may that be? But lookye here, my lad; I arn’t a sir—on’y a marrineer.”

“A what, sir?” said the boy, staring.

“Marrineer—seaman. Fore the mast man, ship now lying off the port o’ Torquay. Whatcher doing there?”

“Cry-ying, sir,” came for answer, with a piteous sob.

“Cry-hying, you young swab?” roared the man, as if he were speaking through a storm. “Here, sop that up. Father been leathering yer?”

“No, sir.”

“No, Jack Jeens!” yelled the man. “Sir, indeed! Jack Jeens—that’s my name. England is my dwellin’ place—leastwise, when I arn’t off France and Spain, or in the ’Terranium leathering the French. Now, then, who has been givin’ it to you? Mother, p’r’aps, and turned you out of doors?”

“No, sir,” sobbed the boy, with a piteous look, in the gathering darkness.

“Yah!” came so savagely that the boy started to run; but the grip upon his shoulder tightened, and he was forced back against the bars of the gate. “Now, just you look here, messmet. You’re such a little un that I don’t like to hit yer for fear you should break; but don’t you haggravate me by talking as if I was a hofficer.”

“No, sir; please, sir—” stammered the boy.

“Hark at him!” growled the man, speaking to one of the stone gate-posts; and then, turning to the other, “Is he a hidgit?”

“No, that I’m not!” cried the boy, speaking indignantly now. “I wanted to say that I had no father and no mother.”

“Then why didn’t you say so at first?” growled the man. “But got no father nor mother?”

“No, s— no, no!” cried the boy.

“You’re a horphan, mate?”

“Yes—Jack Jeens, didn’t you say you were?”

“Right, boy; and that shows me straight and plain that you ain’t a hidgit. Shake hands, mate. I’m just the same as you. I’m a horphan, too, on’y I don’t pipe my eye like you do.”

The boy held out his hand, which the next moment lay, looking dimly white, in the great, hairy paw which seized it.

“Leave crying to the women, my lad. Now then, what’s the matter?”

The tears started to the boy’s eyes again and he uttered a kind of gasp as he strove to master the desire to sob aloud, and said in a broken voice:

“I’m tired and cold and hungry.”

“Eh? Then why don’t you go home?”

“I have no home now,” said the little fellow, sadly.

“That’s queer agen,” said the sailor, in quite a sympathetic tone now. “You’re a horphan like me, and now you’ve got no home. What, nowhere to go and sleep to-night?”

“No—” said the boy, and the word “sir” nearly slipped out again.

“Why, you’re quite a ship in distress, messmet, and it seems lucky you’ve failed in with me. Hungry and out o’ water, are yer?”

“Very hungry, please,” said the boy; “but I found some water over there, running by the roadside, before it was dark, and I drank some.”

“Ah, that’s why it came out o’ them eyes o’ yourn like a shipped wave out o’ the scuppers. Well, I got a shot or two yet in the locker, so come along o’ me and I’ll get yer something to eat, anyhow. Here, hook on to my fin.”

The man’s tone was so friendly, and he held out his hand in such a kindly way, that the little fellow caught at it eagerly, and with the darkness thickening fast, began to trot beside his new friend as he strode off, but only to totter breathlessly at the end of a few minutes and then stumble, ready to fall but for the strong arm which dragged him up.

“Why, hillo!” cried the man. “What’s this here?”

“I—I don’t know,” said the boy, feebly. “I’m so tired—and my feet hurt—and—and—and I can’t go any farther, please. Don’t be cross with me, sir; I can’t help it—I’m obliged to cry.”

His legs sank beneath him as he spoke and doubled so that he naturally came down upon his knees, and raising the hand that was not held, to join the other, the boy seemed in the gloom to be praying for mercy to the big, rough man.

“Why, matey, I didn’t know you were on your beam ends like this here,” he growled, softly. “Here, I’ll help yer. Let me lift yer on to this ’ere bank. That’s the way. Steady, now, while I turn round. Give’s t’other fin. There you are. Heave ho! and you’re up and on my back. Now, then, I’ll tow you into port where I’m going, and you an’ me’ll have a bit o’ supper together, and after that—well, look at that now!”

As he spoke the sailor had got the boy up on his shoulders, pig-a-back fashion, and began to tramp steadily along the road, not feeling the light weight, and talking pleasantly to the little fellow all the while, till, in his surprise, he uttered the last words in a low tone, and followed them up by exclaiming:

“Tired out, poor bairn. I’m blessed if he ain’t fast asleep!”

The sailor stood in the middle of the road thinking and talking aloud to himself as if he were someone else.

“This here’s a pretty set-out, Jack Jeens,” he growled softly, so as not to awaken his load. “Here you are, my lad, just finished your holiday, spent half your arnings along with your  friends, and give t’other half to yer old mother to help her along till you come back from sea again—bless her old heart! On’y I wish when she kisses yer and says, ‘good-bye, and bless you, my dear boy!’ she wouldn’t cry quite all over yer. But as I was a-saying, Jack, here you’re going back quite comfy to join the Sairy Ann schooner, lad, with nothing to do but join your ship, when down upon you comes this here boy, tired and hungry, and crying as bad as your old mother, my lad. You didn’t want a boy, Jack, and now you’ve got him you don’t know what to do with him, nor who he is, nor where he’s going, nor where he comes from. Strikes me he don’t know himself. Take him aboard the Sairy Ann, my lad, and show him to the skipper. ‘Now, then,’ says you, ‘here’s a boy.’ ‘So I see,’ says the skipper. ‘Well, what’s to be done with him?’ says you, and he turns it over in his mind, and ’fore you know where you are he’s settled it all and told you what to do and where to put him.

friends, and give t’other half to yer old mother to help her along till you come back from sea again—bless her old heart! On’y I wish when she kisses yer and says, ‘good-bye, and bless you, my dear boy!’ she wouldn’t cry quite all over yer. But as I was a-saying, Jack, here you’re going back quite comfy to join the Sairy Ann schooner, lad, with nothing to do but join your ship, when down upon you comes this here boy, tired and hungry, and crying as bad as your old mother, my lad. You didn’t want a boy, Jack, and now you’ve got him you don’t know what to do with him, nor who he is, nor where he’s going, nor where he comes from. Strikes me he don’t know himself. Take him aboard the Sairy Ann, my lad, and show him to the skipper. ‘Now, then,’ says you, ‘here’s a boy.’ ‘So I see,’ says the skipper. ‘Well, what’s to be done with him?’ says you, and he turns it over in his mind, and ’fore you know where you are he’s settled it all and told you what to do and where to put him.

“That’s the way to do it,” said Jack Jeens, with a low, soft chuckle. “Poor little bairn! The skipper has got a wife and little uns of his own, and understands these sort o’ things. Shouldn’t wonder if he finds a new father and mother for him.”

Jack’s messmates said nothing, for they never knew, though the rough sailor began to carry out his plan, going onward with the boy fast asleep upon his back, too much wearied out to heed where he was going or to think of the troubles which had befallen one so young. For his sleep grew deeper and deeper till the lights of Torquay came into sight round about the port at the bottom of the hill; and he did not stir when Jack, stopping short at the door of a shabby-looking little inn upon the Strand—a place much frequented by seamen—and the boy did not heed Jack Jeen’s voice when he cried, “What cheer?” to the landlady, and asked for a room and bed for the night with supper to be ready directly.

The simple supper was soon placed upon the table of the mean-looking room; but the boy could not eat.

“Tired out?” said the landlady, sourly.

“Ay, ay; that’s it,” said Jack. “Here, missus, I’ll carry him up and put him to bed.”

And this the rough fellow did, carrying his young companion as carefully as if he were afraid that he would break, and then without attempting to undress him, he laid him down, covered him up, and then went back to have his supper. After which, weary enough himself, and thinking about his work in the early morning, he looked out to where his schooner lay moored to a buoy with a light swinging high in the rigging, and then went up to his room.

The boy was faster than ever, and as Jack Jeens held a guttering tallow candle over the sleeper’s face, “Poor little chap,” he said, smiling. “Why, if I get tumbling into bed it’ll wake him up, and I won’t do that. Here, this’ll do.”

Jack took the candle out of the stick and put it out very untidily by turning it upside down till the flame was choked, and then threw himself down upon the floor by the bedside.

“Quite as soft—bit softer perhaps—than the schooner’s deck,” he muttered. “Good-night, little un. The skipper’ll make it all right for you in the morning, and—Heigh-ho-ha-hum! My word, I am jolly sleepy, and—”

Jack Jeens said no more, but the next instant he gave vent to a snore that ought to have awakened the boy but did not; and he lay sleeping hard till there was something louder than his own snore upon the stairs.

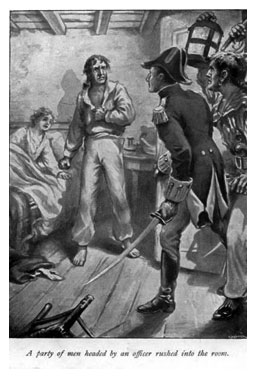

First there was the whispering of voices below; then a rough laugh; then the shuffling and stamping of feet, which ceased upon the landing outside the door, which was roughly tried, and being fastened, kicked in, while a fierce voice cried aloud in tones which made Jack Jeens spring to his feet under the belief that he was at home aboard the schooner and in his bunk.

“Ahoy there! Tumble up! Tumble up! In the King’s name!”