Chapter 5 | The Powder Monkey

Phil sprang out of the hammock at the first sound of a whistle, looking rested and quite content, as he readily answered Jack’s question about sleeping well.

Then followed other questions put by half-awake sailors as to who he was and how he came there—questions which began to trouble the little fellow, till Jack Jeens came to his help.

“Who is he?” cried the big bluff sailor. “Why, he’s my boy. He was pressed along with me, and he’s going to be a powder monkey.”

“Rather a little un, eh?” said one joker. “Why, youngster, you’ll do to get in and sponge out the guns, only you must mind and not get stuck in the touch-holes.”

But Phil’s appearance was enough to make all the men his friends, and almost made Jack their enemy, for a strange kind of jealousy sprang up as the crew made efforts to entice the little fellow away from his companion. But the ill feeling soon died out, for though Phil had a smile and a bright look for everyone, Jack Jeens was his great attraction, and he was never happier than when he was at the big, rough fellow’s side.

The novelty of such a little fellow becoming one of the crew soon died out, and in a few days he was so much at home, that the men treated him as one of themselves, while the officers soon took his presence as a matter of course, and had a nod or a smile for the active little fellow who had become the pet of the ship.

“Why, you’ve quite put the tabby Tom cat’s nose out of joint,” said Jack one day, with a grin. “Has he scratted you yet?”

“No, of course not,” cried Phil. “He follows me wherever I go.”

“Humph!” grunted Jack. “Everybody and everything seems to like you, old chap.”

Phil said nothing, but he thought a good deal, knowing only too well as he did that his friend Jack was not right. For there were several other boys on board who, seeing the favour in which the little new-comer stood, were not long in trying to make his young life a burden. All far bigger and stronger, they soon began to persecute him when they found a chance, one of their favourite plans being to, as they called it, “chivvy him” and hunt him about the vessel.

Soon after dawn one morning Phil had crept on deck to stand looking over the bulwark through the soft grey light at the scattered vessels sailing slowly along, when all at once a faint whish caught his ear, and turning sharply he saw one of his persecutors creeping cautiously towards him, followed by half-a-dozen more, while a couple had crossed the deck and were ready to cut him off if he attempted to retreat in that direction.

Phil glanced towards the forecastle hatch, but there was a boy rising from the square opening, and he turned to look aft, but only to see that other lads were waiting there. For the enemy had taken steps to cut him off in every direction, and the little fellow looked wildly round for a way of escape, and then made a rush to pass through his tormentors, who cut him off at once and with a cry of delight dashed in.

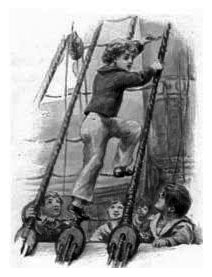

It was all very quickly done; first one and then another of the lads nearly had him, but active as a monkey that has no dealings with powder, Phil dodged, feinted, and dodged again, brushing by the foremost of his pursuers, making for the starboard  bulwark, and reaching the foremast shrouds before the first boy could recover himself.

bulwark, and reaching the foremast shrouds before the first boy could recover himself.

The last was after him, though, directly, but too late; for with a bound Phil had sprung up, caught at the nearest rope, swung himself on to the rail, and then begun swarming up the rigging, a mere morsel of a fellow, as he dragged himself up from ratline to ratline, mounting higher and higher towards the foretop.

Sure of him now, the boys uttered a low cry of delight, and while two made for the starboard shrouds to follow him, a couple more made for the larboard, or port, as they call them now, while the rest gathered below.

“Take a turn round him with the halyards!” whispered one boy, from the deck, “and then send him down to us.”

Phil heard, and climbed on breathlessly, looking up the while at the top and thinking that if his enemies followed him there he could climb higher.

The fore top was reached, but this proved no sanctuary, and Phil had to climb higher still, for one boy in particular, the most active and daring of the party, followed fast and with such good effect, that to Phil’s horror just before he reached the top gallant cross-trees, his pursuer was so close behind that he made a dash at his quarry’s ankle, and grasped it; and in his horror Phil made a spring which took him out of his enemy’s reach and proved disastrous.

For the boy had thrown so much energy into his action that as Phil’s ankle glided through his hand, he failed to clutch the ratline beneath, swung round, and unable to get a fresh hold, began to fall from rope to yard, to rope again, and then came heavily on the fore yard, which partially broke his fall, but after a moment or two he came down heavily upon the deck, making his companions there scatter and then make for the forecastle hatch, while those aloft scuttled down as hard as they could.

As for Phil, white with horror, and feeling strongly that he was the cause of the accident, he clung to the shrouds, looking wildly down for a few moments, before seizing the halyards and sliding gradually down to reach the fallen boy lying alone, and began to feel him all over in silence, before his hand came in contact with the insensible lad’s leg in such a way that the little fellow uttered a shriek of horror which brought the men of the watch to his side.

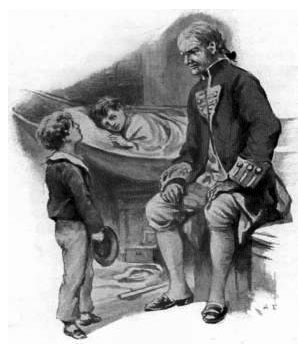

Phil turned sick as he stood there listening to what was said; but he fought it back and walked with them as they raised the insensible boy from the deck and bore him to the cockpit, where the surgeon was soon busy setting and bandaging, and talking sourly the while in his ill-humour at being roused from his morning’s sleep.

His words consisted of scoldings and questionings.

“You young dog,” he said to Phil, who was the only boy allowed to be present. “Skylarking in the rigging before breakfast! What could you expect? Well, my young shrimp, you have the satisfaction of knowing that you’ve broken your companion’s leg, and you’ll have to be his nurse. Do you hear?”

“Yes, sir,” said Phil; “but he won’t die, will he?”

“Not if I know it, boy. Ah, he’s coming-to now.”

For the injured lad opened his eyes, to stare about him, trying to understand what it all meant, and grinning as he saw Phil.

“I say,” he whispered, “I caught you!”

“That you didn’t!” said Phil, indignantly.

“Well, nearly. But what’s the matter with my leg?”

“Broke,” said Phil, in a whisper.

“That all?” said the boy, coolly. “Well, then, I sha’n’t be able to walk.”

“No,” said Phil, in a hurried whisper. “You’re to be in hospital, and he says I’m to be your nurse.”

“Who? The doctor?”

“Yes, sir,” said that individual, sharply. “Your right leg’s broken just below the knee, and you may think yourself very lucky it wasn’t your neck.”

Phil turned upon him an indignant look which made the doctor stare.

“Be a warning to you both not to play such monkey tricks again,” he added, sourly. “There, little one, stop with him, and I’ll tell one of the men to bring you some breakfast here.”