Chapter 4 | The Powder Monkey

Jack Jeens found himself at last piped down below, swinging his hammock and turning in like the rest, to lie listening to the wash of the waves against the rolling sides of the great man-of-war, whose timbers creaked and groaned, for a stiff breeze had sprung up as the fleet began to run down channel. A rough night at sea did not trouble Jack, but he lay thinking about little Phil and wondering whether he could do any good by getting out of his hammock and trying to find him in the darkness; but he felt nothing but despair as he knew enough about a man-o’-war besides what he had seen during the time he had been on board, to feel sure that if he began to search he would soon be stopped by the marine sentries or by the watch.

“A man can’t do as he likes aboard a King’s ship,” he said to himself dismally, as he lay in the black darkness, “but only let me get this night over, and they may say what they like, I’ll go straight to the captain, or to Lord Nelson himself, and ask him to have that little fellow found. Here, what’s that?”

He said those last three words half aloud, for he had suddenly felt something cold brush across his face.

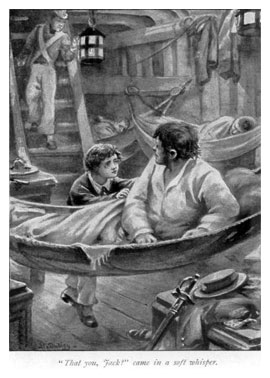

“That you, Jack?” came in a soft whisper.

“Yes. That you, little messmet? Hooroar! Give’s your fin.”

“Promise me you won’t send me home, Jack, and I will.”

“Send you home, messmet!” growled the rough sailor,  whose voice trembled with emotion. “Why, o’ course I won’t! You’re to stay aboard, and be a powder monkey. My word! Your hands are like ice! Where have you been all day?”

whose voice trembled with emotion. “Why, o’ course I won’t! You’re to stay aboard, and be a powder monkey. My word! Your hands are like ice! Where have you been all day?”

“Down in the dark, and it was so cold,” said the little fellow, shivering. “But you won’t send me back, Jack? I can’t—I can’t go.”

“Send yer back? Not me!” growled the sailor. “On’y too glad to get yer again. Don’t I tell yer that you’re one o’ the King’s men now, and are going to stop? My word, you are cold! Here, heave ho! That’s got you! You snuggle up here alongside me. King’s man! Why, you’re not much bigger than a frog, and just as cold. My hammock feel warm?”

“Oh, so warm—so warm, Jack!” came in a whisper, as two little hands were passed round the rough fellow’s neck.

“That’s right, little un. But are you hungry?”

“No, not very; only cold and tired, Jack. But I don’t mind now you’re not going to send me home. Oh, Jack, I do feel so happy and comfortable!”

“That’s right, but I say, little un, it’s making you cry again. That don’t seem so very happy, do it?”

“Yes, it’s because I’m so very, very happy, Jack; but don’t speak to me for a bit.”

“Right, but what’s the matter? You’re not going to get out again, are you?”

“No, but don’t speak, please,” whispered the little follow. “I’m afraid some of the other men will hear.”

Jack Jeens, the rough sailor, drew a deep breath, as he held on to Phil’s jacket to make sure that he did not fall out, as he struggled up at the side of the hammock; and then for some little time he did not stir, while the huge vessel rolled and creaked and groaned, through which sounds came the heavy breathing of the men swinging in their hammocks.

But at last the future powder monkey crept softly back into his old place and passed his arms round the rough sailor’s neck, and a curious thrill of satisfaction ran straight to Jack Jeens’ heart as he felt two little lips press his cheek, and heard a pleasant, soft voice whisper:

“Good-night, Jack. God bless you!”

It was not many minutes afterwards, and while the light from the swinging lanthorn close up to the companion ladder by the marine sentry had turned so dim that the man had opened the half transparent door to snuff the candle within, that Jack Jeens, whose eyes in the gloom felt a little moist, muttered to himself.

“He said ‘good-night. God bless you, Jack!’ he did. And on’y think of it—him amongst all these rough chaps a-sleeping here in the dark—kneels up in my hammock, he did, poor little chap, and says his prayers!”