Chapter 3 | The Powder Monkey

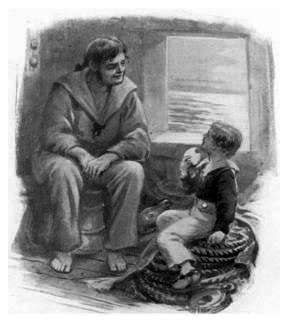

Jack Jeens sat upon the bottom of an upturned bucket with his elbows resting upon his knees, gazing down at his young companion of the previous night’s adventure, who was half sitting, half lying, upon the lower deck of the great ship, close to the open port-hole, through which the morning light shone upon his face as he went on eating a biscuit, through the edge of which his keen pearly-white teeth passed like those of a mouse.

It was light enough close to the boy, but all inward was very gloomy, and every here and there a lanthorn was burning dimly, although it was morning.

There was plenty of noise and bustle going on about the deck where the lanthorns burned, and the trampling of feet, and shouts that sounded like orders came now and then; but the principal sound just there by the port-hole through which the light came was the crunch, crunch, crunch of the biscuit.

At last Jack Jeens spoke.

“It caps me,” he said. “Seems wonderful. Here you are, just aboard ship for the first time, and ’stead o’ being badly and sick, eating away like a reg’lar biscuit nibbler.”

“I was so hungry,” said the little fellow, with a bright smile.

“Eat away, then,” said Jack; “but I say, arn’t you frightened?”

“Not now,” said the boy. “I was when those sailors came and woke me up.”

“Course you would be,” said Jack. “Why, it scared me. But arn’t you frightened now?”

The boy shook his head and took another bite at the hard biscuit.

“Why arn’t you frightened?” said Jack, after a good long stare at the biscuit-nibbler, as he called his companion.

“Because you’re here,” said the boy.

“Yes, I’m here, o’ course,” said Jack, staring hard as if puzzled. “I’m a-sitting close to yer; but that don’t make no difference because I’m a pressed man.”

“You’ll take care of me and see that no one hurts me,” said the boy, confidently.

“Oh, o’ course,” said Jack, scratching his head. “That is, while I’m here, but what’s going to become of you when I’m gone?”

“Gone?” said the boy, sharply, as he left off eating. “You’re not going away to leave me, are you?”

“Well, no,” said Jack, grimly. “It’s you who are going away to leave me.”

“That I sha’n’t,” cried the boy, quickly. “I’ll never go away from you. I like you.”

“That’s right,” said Jack Jeens, grinning with satisfaction; “and of course I like you too, youngster. But they’ll be setting you ashore soon, so that you can go back to your folk.”

The boy shook his head.

“What do you mean by that?” said the sailor, sharply. “Lookye here, you never told me what your name was, nor where you come from.”

The little fellow frowned and looked pained.

“Got a name, haven’t you?” said the sailor.

“Yes, of course,” cried the boy. “Phil.”

“Phil, eh?” said the sailor. “Phil what?”

“Leigh,” was the reply.

“Phil Leigh, eh? Hard a-lee. Well, where do you live?”

“At Greyton,” said the boy, slowly and sadly. “No, I used to live there, till—till—till—”

“Yes, I know,” said Jack, quickly, as he grasped the meaning of the boy’s working face. “But why don’t you live there now?”

“Because uncle came,” said the boy, with a shudder, “and then I—I—You won’t take me back, will you?”

“Dunno yet,” said Jack, sternly. “Boys arn’t got no business to run away from home. Watcher run away for?”

“He used to beat me so.”

“Beat you—a little un like you?” cried Jack, with a look of disgust. “What with?”

“Walking stick.”

“Thick un?” said Jack, and the boy nodded. “And didn’t nobody stop him?”

“Yes,” said the little fellow quickly. “Aunt did.”

“Who’s aunt?” said Jack, sharply.

“Why, my aunt. She said it was a shame.”

“Ha! I like her,” said Jack, and he rubbed his hands. “But what did he beat you for?”

“He said I was always crying,” said the boy, piteously. “But I couldn’t help it.”

“Course you couldn’t,” said Jack, softly. “You cried a-cause o’ them being took away, didn’t you?”

The boy nodded sharply—he did not dare to speak.

“Ha!” sighed Jack Jeens, as he rubbed his hands softly together. “I wish I’d been there. But I say, look here. And so you run away because he whipped you?”

The boy nodded.

“And went on walking till I run again’ you?”

“Yes,” came like a sigh.

“Well, you see, you’ll have to go back.”

The little fellow dropped the piece of biscuit he held, and it fell with a rap upon the deck, as he started to his feet, glanced out of the open port-hole, and took a quick step or two towards it, darted off into the darkness of the ’tween decks, the sailor catching a glimpse of him as he passed the light shed by the lanthorns.

“Scared, that’s what he is,” muttered Jack. “Why, I do believe that in his fright he’d ha’ jumped into the water and swum for it sooner than be sent back. Well, I must find him again; and it don’t seem easy in a great ship like this. Poor little chap, he was ’most ready to jump out of his skin!”

Jack took a few steps cautiously in the direction followed by the little fellow, but he had hardly started before the sound of a shrill whistle rang out, and he and some ten more pressed men were ordered on deck to be examined by the first lieutenant and some of the other officers, before being informed that they were now King’s men, and ordered to receive their kits, after which they were distributed amongst the crew according to whether they were land or sea men, the latter having little to learn.

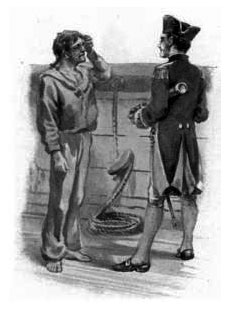

Jack uttered a grunt as he learned his destination, which was to be under the order of the captain of one of the big guns on the main deck, and the meaning of that grunt was that he determined to make the best of it. But his grunt sounded deep, because he had little Phil Leigh upon his mind, so he addressed one of the officers, and stated his case.

“Eh? The boy brought aboard with you when you were pressed?”

“Yes, sir,” said Jack. “Run away from home, he did. Uncle thrashed him. Young gen’leman he is, and I want you to put him in a boat and set him ashore.”

“Oh! do you, my lad?” said the officer, gruffly. “Run away from home, did he?”

“Yes, sir, because—”

“That’ll do, my lad; no more talk. If he has run away from home he has run into the very best place to learn how to be a good boy.”

“But—”

“That’ll do, sir. I’ve no time to listen to you. We want boys.”

“But he’s such a little un, sir,” pleaded Jack.

“Then we’ll feed him well and make him grow big. Where is he?”

“Dunno, sir. He run away again this morning.”

“What, again?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ah, well, he can’t run far, and we shall find him soon. Set him ashore, eh? Next shore we shall see will be somewhere on the coast of Portugal or Spain, I expect.”

The officer said the last words to himself as he tramped away, leaving Jack Jeens to stand scratching his head and muttering.

“Pore little chap!” he said. “They’ll make a powder monkey on him? Well, and a fine thing too. Better than being a boy at home with an uncle who gave him the stick for crying after his father and mother who are dead. Here, Phil, messmate, where are yer?” he said softly, and his voice sounded as if somehow he had a soft place in his rough, honest heart. “Where are yer, little un? I want to tell you that you’re going to be powder monkey aboard Admiral Lord Nelson’s ship.”