Chapter 38 | Suggestions of Escape | Yussuf the Guide

The morning broke so bright and clear, and from the window there were so many wonders of architecture visible in the old stronghold, that the professor and Lawrence forgot for the time that they were prisoners, and stood gazing out at the wonderful scene.

Where they had been placed was evidently a portion of an old castle, and looking down there were traces of huge buildings of the most solid construction, such as seemed to date back a couple of thousand years, and yet to be in parts as strong as on the day they were placed and cemented stone upon stone.

Huge wall, tremendous battlement, and pillared remains of palace or hall were on every side, and as they gazed, it seemed to them that they could easily imagine the presence of the helmeted, armoured warriors who had once owned the land.

The sun was so glorious that the professor proposed a look round before breakfast.

“Never mind the inconvenience, Lawrence,” he said, “we have fallen into a wonderful nest of antiquities, worth all our journey and trouble. Here, come along.”

They went to the doorway, drew the great rug hanging before it aside, and were stepping out when a couple of guns were presented at their breasts, and they were angrily bidden to go back.

It was a rude reminder that they were no longer upon a touring journey, and the fact was farther impressed upon them, after a breakfast of yaourt or curd, bread, and some very bad coffee, by a visit from the chief and half a dozen men.

Yussuf was called upon to interpret, and that which he had to say was unpalatable enough, for he had to bid them empty their pockets, and pass everything they possessed over to their captors.

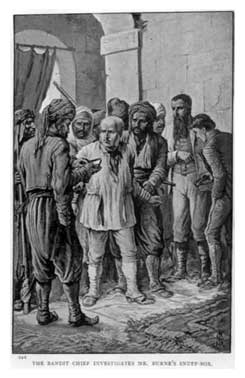

Watches, purses, pocket-books, all had to go; but it was in vain to resist, and everything was handed over without a word, till it came to Mr Burne’s gold snuff-box, and this he slipped back into his pocket.

The attempt to save it was in vain; two sturdy scoundrels seized him, one on each side, and the snuff-box was snatched away by the chief himself.

He uttered a few guttural sounds as he opened the box, and seemed disappointed as he found therein only a little fine brown dust, into which he thrust his finger and thumb.

He looked puzzled and held it to his nose, giving a good sniff, with the result that he inhaled sufficient of the fine dust to make him sneeze violently, and scatter the remainder of the snuff upon the earth.

Mr Burne made a start forward, but he was roughly held back, and the chief then turned to Yussuf.

“Tell them,” he said in his own tongue, “to write to their friends, and ask for the ransom—two thousand pounds each, and to say that if the money is not given their heads will be sent. Bid them write.”

The fierce-looking scoundrel turned and stalked out of the place with his booty, and the moment he was free, Mr Burne dropped upon his knees and began sweeping the fallen snuff together in company with a great deal of dust and barley chaff, carefully placing the whole in his handkerchief ready for clearing as well as he could at his leisure.

“That’s just how they served us,” said Mrs Chumley dolefully. “I thought they would treat you the same.”

“So did I,” said her husband dolefully. “They’ve got my gold repeater, and—”

“Now, Charley, don’t—don’t—don’t bother Mr Preston about that miserable watch of yours, and I do wish you wouldn’t talk so much.”

“But we must talk, madam,” cried Mr Burne. “Here, you, Yussuf, what’s to be done?”

“I can only give one piece of advice, effendi,” said Yussuf gravely; “Write.”

“What, and ruin ourselves?”

“Better that than lose your life, effendi,” replied the guide. “These people are fierce, and half savage. They believe that you have money, and they will keep their word if it is not sent.”

“What, and kill us, Yussuf?” said Lawrence, with a horrified look.

“Not if I can save you, Lawrence effendi,” said Yussuf eagerly. “But the letters must be sent. It will make the villains think that we are content to wait, and put them off their guard. Preston effendi, it is a terrible increase of the risk, but you will take the lady?”

“Take the lady?”

“Hush! When we escape. Do not say more now; we may be overheard. Write your letters.”

“Then you mean to try and escape.”

“Try and escape, effendi?” said Yussuf with a curious laugh; “why, of course.”

“What will you do?”

“Wait, excellency, and see. There are walls here, and I think places where we might get down past the guards with ropes.”

“And the ropes?”

Yussuf laughed softly, and stared at the rugs as he said quietly:

“I can see the place full of ropes, your excellency; only be patient, and we’ll try what can be done in the darkness. Write your letters now.”

Mr Preston had to appeal to the sentries, through Yussuf, for the necessary writing materials, and after a good deal of trouble his own writing-case, which had been in the plundered baggage, was brought to him. He wrote to the vice-consul, Mr Thompson, at Smyrna, telling of their state, and asking advice and assistance, telling him, too, how to obtain the money required if diplomacy failed, and the ransom could not be reduced.

This done, and a similar letter being written by Mr Burne, the sentry was again communicated with, and the despatches sent to the chief.

An hour later there was a little bustle in the open space before their prison, and a couple of well-armed men mounted their horses, the chief standing talking to them for a few minutes, as if giving them final instructions.

He then summoned his prisoners, and spoke to Yussuf, bidding him ask Mr Burne, whose wonderful head-dress won for him the distinction of being considered the most important personage present, whether he would like to make any addition to his despatch; for, said he:

“I have told the people that any attempt at rescue means your instant death. I will wait any reasonable time for your ransoms, and you shall be well treated; but I warn you that attempts to escape will be death to you. That is all.”

“Wait a minute, Yussuf,” said Mr Burne. “Tell him he can keep the snuff-box and welcome, but he has a canister of best snuff in the package that was on the brown pony. Ask him to let me have that.”

“Yes,” said the chief, on hearing the request, “it is of no use to anyone. He can have it. What a dog of a Christian to take his tobacco like that! Anything else?”

“Yes,” said Mr Preston, on hearing the reply, “tell him to send his men to watch me as much as he likes, but I want leave to inspect the old ruins and to make drawings. Tell him I will not attempt to escape.”

“No, effendi,” said Yussuf, “I will not tell him that, but I will ask the first;” and he made the request.

“What! is he—one of the idiot giaours who waste their time in seeing old stones and imitate them upon paper?”

“Yes, a harmless creature enough,” said Yussuf.

“So I suppose, or he would have fought. Well, yes, he can go about, but tell him that if he attempts to leave my men behind they will shoot him. Not that he can get away, unless he has a djin to help him, or can fly,” he added with a laugh.

He walked to his men, gave them some further instructions, and they saw the two ambassadors go in and out among the ruins till they passed between two immense buttresses of rock, and then disappear down the perilous zigzag path that led to the shelf-like way.

“Yes,” said Yussuf, looking at Mr Preston, and interpreting his thoughts, “that is the only way out, excellency, but I do not despair of making our escape. It must be a long time before arrangements can be made for your release, and the winter comes early here in these high places.”

“Winter?” cried Lawrence.

“Yes,” said Yussuf. “It is fine and sunny one day, the next the snow has fallen, and a place like this may be shut off from the plains below for months. You do not wish to pass the winter here, Lawrence effendi?”

“I don’t think I should mind,” replied the lad, “everything is so fresh, and there is so much to see.”

“Well, now they are giving me leave to go about,” said Mr Preston thoughtfully, “I think I could spend some months in drawing and writing an account of this old city, especially if they would let me make some excavations.”

“But his excellency, Mr Burne?” said Yussuf.

“Oh! I’ve got my snuff—at least I am to have it, and if they will feed us well I don’t suppose I should mind very much. The fact is, Preston, I’ve been working so hard all my life that I like this change. Doing nothing is very pleasant when you are tired.”

“Of course it is,” said the professor smiling.

“And so long as there’s no nonsense about cutting off men’s heads, or any of that rubbish, I rather like being taken a prisoner by brigands. I wonder what a London policeman would think of such a state of affairs.”

“My masters are submitting wisely to their fate,” said Yussuf gravely; “and while we are waiting, and those people think we are quite patient, I shall come with his excellency Preston, and while he draws I shall make plans, not of the city, but how to escape.”

Further conversation was cut short by the coming of Mr and Mrs Chumley, who eagerly asked—at least Mr Chumley wished to ask eagerly, but he was stopped by his lady, who retained the right—what arrangements had been made. And she was told.

“Oh, dear!” she sighed, “then that means weary waiting again. Oh, Charley! why would you insist upon coming to this wretched land?”

Mr Chumley opened his mouth in astonishment, but he did not speak then, he only waited a few minutes, and then took Lawrence’s arm, and sat whispering to him apart, telling him how Mrs Chumley had insisted upon coming to Turkey when he wanted to go to Paris, and nowhere else, and that he was the most miserable man in the world.

Lawrence heard him in silence, and as he sat he wondered how it was the most miserable man in the world could look so round and happy and grow so fat.