Chapter 18 | Mr Burne Blows His Nose | Yussuf the Guide

“At last!” cried Lawrence, as they set off for their first incursion. Two more days had been occupied in purchasing stores, saddlery, and other necessaries for their trip, and, as the lad said, at last they were off.

The start of the party excited no surprise in the little town. It was nothing to the people there to see four well-armed travellers set off, followed by a sturdy peasant, who had charge of the two heavily-laden pack-horses, for, in addition to the personal luggage and provisions of the travellers, with their spare ammunition, it was absolutely necessary to take a supply of barley sufficient to give the horses a good feed, or two, in case of being stranded in any spot where grain was scarce.

The heat was very great as they rode on over the plain, and Mr Burne’s pocket-handkerchief was always busy either to help him sound an alarm, to wipe the perspiration from his brow, or to whisk away the flies from himself and horse.

“It’s enough to make a man wish he had a bushy tail,” he said, after an exasperated dash at a little cloud of insects. “Peugh! what a number of nuisances there are in the land!”

But in a short time, enjoying the beautiful prospects spread around, they rode into a wooded valley, where the trees hung low, and, as they passed under the branches, the trouble from the virulent and hungry flies grew less.

The ascent was gradual, and after a few miles the woodland part ceased, and they found themselves upon a plain once more, but from the state of the atmosphere it was evidently far more elevated than that where the town lay. Here for miles and miles they rode through clover and wild flowers that lay as thick as the buttercups in an English meadow. But in addition to patches of golden hue there were tracts of mauve and scarlet and crimson and blue, till the eyes seemed to ache with the profusion of colour.

So far the ride had been most unadventurous. Not a house had been seen after they had quitted the outskirts of the town, nothing but waste land, if that could be called waste where the richest of grasses and clovers with endless wild flowers abounded.

At mid-day a halt was made beneath a tremendous walnut-tree growing near a spring which trickled from the side of a hill; and now the horses were allowed to graze in the abundant clover, while the little party made their meal and rested till the heat of the day was past.

Here Yussuf pointed out their resting-place for the night—a spot that lay amid the mountains on their right, apparently not far off; but the Muslim explained that it would be a long journey, and that they must not expect to reach it before dark.

After a couple of hours the horses were loaded again, and sent on first with their driver, while the travellers followed more leisurely along the faint track for it could hardly be called a road. The second plain was soon left behind, and their way lay among the hills, valley after valley winding in and out; and as fast as one eminence was skirted others appearing, each more elevated than the last, while the scenery grew wilder and more grand.

The little horses were behaving very well, trudging along sturdily with their riders, and every hour proving more and more the value of Yussuf’s choice. There was no restiveness or skittish behaviour, save that once or twice the little cream-coloured fellow which Lawrence had selected for himself and christened Ali Baba had shown a disposition to bite one of his companions. He soon gave up, though, and walked or trotted steadily on in the file, Yussuf leading, the professor coming next, then Lawrence, and Mr Burne last.

They stopped at various points of the rising road to study the grand patches of cedars, clumps of planes low down in the valleys, and the slopes of pines, while in the groves the thrushes sang, and the blackbirds piped as familiarly as if it was some spot in Devonshire instead of Asia Minor. Then a diversion was made here and there to examine some spring or the edge of a ravine where a stream ran. There was plenty of time for this, as the two baggage-horses had to be studied, and they were soon overtaken after one of these rides.

But at last a visit to a few stones on a hillside, which had evidently been a watch-tower in some old period of this country’s history, took up so much time that the man with the baggage was a good hour’s journey ahead; and as they reached the track once more Yussuf turned to ask the professor whether he thought the invalid could bear the motion if he led the way at a trot.

The professor turned to ask Lawrence, who replied that he believed he could, and then something happened.

The professor had hardly spoken and obtained his reply before Mr Burne, who had been refreshing himself with a pinch of snuff, whisked out his handkerchief according to his custom.

They were now going along a valley which ran between too highish walls of rock, dotted here and there with trees—just the sort of place, in fact, where anyone would be disposed to shout aloud to try if there was an echo; but the idea had not occurred to either of the travellers, whose thoughts were bent upon overtaking the baggage animals with their stores, when quite unexpectedly Mr Burne applied his handkerchief to his face and blew his nose.

It was not one of his finest blasts, there was less thunder in it, and more high-pitched horn-like music, but the effect was electrical.

There was an echo in that valley, and this echo took up the sound, repeated it, and seemed to send it on to a signalling station higher up, where it was caught and sent on again, and then again and again, each repetition growing weaker and softer than the last.

But only one of these echoes was heard by the travellers, for, as afore said, the effect was electrical.

The moment that blast was blown behind him, Ali Baba, Lawrence’s cream-coloured horse, threw up his head, then lowered it, and lifted his heels, sending his rider nearly out of his saddle, uttered a peculiar squeal, and set off at a gallop.

The squeal and the noise of the hoofs acted like magic upon the other three horses, and away they went, all four as hard as they could go at full gallop, utterly regardless of the pulling and tugging that went on at their bits.

This wild stampede went on along the valley for quite a quarter of an hour before Yussuf was able to check his steed’s headlong career; and it was none too soon, for the smooth track along the valley was rapidly giving way to a steep descent strewed with blocks of limestone, and to have attempted to gallop down there must have resulted in a serious fall.

As it was, Yussuf was only a few yards from a great mass of rock when his hard-mouthed steed was checked; and as the squeal of one had been sufficient to start the others, who had all their early lives been accustomed to run together in a drove, so the stopping of one had the effect of checking the rest, and they stood together shaking their ears and pawing the ground.

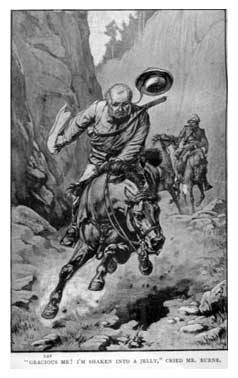

As soon as he could get his breath, Lawrence began to laugh, and Mr Preston followed his lead, while the grave Muslim could not forbear a smile at Mr Burne. This worthy’s straw hat had been flying behind, hanging from his neck by a lanyard, while he stood up in his stirrups, craned his neck forward, and held his pocket-handkerchief whip fashion, though it more resembled an orange streak of light as it streamed behind; while now, as soon as the horse had stopped, he climbed out of the saddle, walked two or three steps, and then sat down and stared as if he had been startled out of his senses.

“Not hurt, I hope, Burne,” said the professor kindly.

“Hurt, sir—hurt? Why, that brute must be mad. He literally flew with me, and I might as well have pulled at Saint Paul’s as try to stop him. Good gracious me! I’m shaken into a jelly.”

“Mine was just as hard-mouthed,” said the professor.

“Hard-mouthed? say iron-mouthed while you are about it. And look here, Lawrence, don’t you make your pony play such tricks again.”

“I did nothing, sir,” expostulated Lawrence.

“Nonsense, sir! don’t tell me. I saw you tickle him with your hand behind the saddle.”

“But, Mr Burne—”

“Don’t interrupt and contradict, sir. I distinctly saw you do it, and then the nasty brute kicked up his heels, and squealed, and frightened the others.”

“But, Mr Burne—”

“Don’t prevaricate, sir, I saw you, and when that brute squealed out you could hear the noise go echoing all down the valley.”

In the most innocent manner—having his handkerchief out of his pocket—the old lawyer applied it to his nose and gave another blast, the result being that the horses nearly went off again; but Yussuf caught Mr Burne’s steed, and the professor and Lawrence managed to hold theirs in, but not without difficulty.

“What! were you doing it again?” cried Mr Burne angrily.

“My dear Burne—no, no; pray, don’t do that,” cried the professor. “Don’t you see that it was you who startled the animals off?”

“I startle them? I? What nonsense!”

“But indeed you did, when you blew your nose so loudly.”

“Blew my nose so loudly! Did I blow my nose so loudly?”

“Did you? why it was you who raised that echo.”

“I? Raised that echo? My dear sir, are you dreaming?”

“Dreaming? No! A ride like that upon a rough Turkish horse does not conduce to dreaming. My dear Burne, did you not know that you made that noise?”

“Noise? What, when I blew my nose, or when I took snuff?”

Lawrence could not contain himself, but burst into another tremendous fit of laughter, while, when the old lawyer looked up at him angrily, and then glanced at Yussuf, it was to see that the latter had turned his face away, and was apparently busily rearranging the bridle of his horse.

“But I say, Preston,” said the old lawyer then, “do you really mean to say that I made enough noise to frighten the horses? I thought it was Lawrence there tickling that biting beast of his.”

“But I did not tickle him, Mr Burne,” protested Lawrence.

“Bless my heart, it’s very strange! What do you say, Preston?—you don’t answer me. It is very strange.”

“Strange indeed that you do not recognise the fact that the tremendous noise you made in your pocket-handkerchief started the horses.”

The old gentleman looked round; then at the horses; then in his handkerchief; and back at the horses again.

“I—er—I—er—I really cannot believe it possible, Preston; I blow my nose so softly,” he said quite seriously. “Would you—there—don’t think I slight your word—but—er—would you mind—I’m afraid, you see, that you are mistaken—would you mind my trying the horses?”

“By no means,” said the professor smiling.

“I will then,” said the old gentleman eagerly; and going up to the horses, yellow handkerchief in hand held loosely as if he were about to use it, he slowly advanced it to each animal’s nose.

They neither of them winced, Lawrence’s cream colour going so far as to reach out and try to take hold of it with his lips, evidently under the impression that it was some delicate kind of Turkish dried hay.

“There,” said Mr Burne triumphantly; “you see! They are not frightened at the handkerchief.”

“Walk behind,” said the professor, “and blow your nose—blow gently.”

The old gentleman hesitated for a moment, and then blew as was suggested, not so loudly as before, but a fairly sonorous blow.

The horses all made a plunge, and had to be held in and patted before they could be calmed down again.

“What ridiculous brutes!” exclaimed Mr Burne contemptuously. “How absurd!”

“You are satisfied, then?” said the professor.

“I cannot help being,” replied Mr Burne. “Bless my heart! It is ridiculous.”

“I am growing anxious, your excellencies,” said Yussuf interrupting. “The time is getting on, and I want to overtake the baggage-horses. Will you please to mount, sir?”

“Bless me, Yussuf,” cried Mr Burne testily; “anyone would think that this was your excursion and not ours.”

“Your pardon, effendi, but it will be bad if the night overtakes us and we have not found our baggage. Perhaps we may have to sleep at a khan where there is no food.”

“When we have plenty with the baggage. To be sure. But must I mount that animal again? I am shaken to pieces. There, hold his head.”

The old gentleman uttered a sigh, but he placed his foot in the stirrup and mounted slowly, not easily, for the horse was nervous now, and seemed as if it half suspected his rider of being the cause of that startling noise.