Chapter 21 | A Skirmish | Yussuf the Guide

“This is a pretty state of affairs,” cried Mr Burne, opening and shutting his snuff-box to make it snap. “Now, what’s to be done?”

“Tramp to the nearest village, I suppose, and buy more,” replied the professor coolly, “We must expect reverses. This is one.”

“Hang your reverses, man! I don’t expect and I will not have them, if I can help it—serves us right for not watching over our baggage.”

“Well, Yussuf, I suppose you are right,” said the professor.

“Yes, effendi. What is to be done?”

“What I say.”

“Yes; what you say,” replied the Turk frowning; “and he is so young. We are only three.”

“What are you thinking, Yussuf?”

“That it makes my blood boil, effendi, to be robbed; and I feel that we ought to follow and punish the dogs. They are cowards, and would fly. A robber always shrinks from the man who faces him boldly.”

“And you would follow them, Yussuf?”

“If your excellency would,” he said eagerly.

The grave quiet professor’s face flushed, his eyes brightened, and for a few moments he felt as if his youthful days had come back, when he was one of the leaders in his college in athletics, and had more than once been in a town-and-gown row. All this before he had settled down into the heavy serious absent-minded student. There was now a curious tingling in his nerves, and he felt ready to agree to anything that would result in the punishment of the cowardly thieves who had left them in such a predicament; but just then his eyes fell upon Lawrence’s slight delicate figure, and from that they ranged to the face of Mr Burne, and he was the grave professor again.

“Why, Preston,” said the old lawyer, “you looked as if you meant fighting.”

“But I do not,” he replied. “Discretion is the better part of valour, they say.” Then, turning to Yussuf—“What is the nearest place to where we are now?”

Yussuf’s face changed. There was a look of disappointment in it for a few moments, but he turned grave and calm as usual, as he said:

“There is a village right up the valley, excellency. It is partly in the way taken by the robbers, but they will be far distant by now. They are riding and we are afoot.”

“But is it far?”

“Half the distance that it would be were we to return to the place we left this morning.”

“Forward, then. Come, Lawrence, you must walk as far as you can, and then I will stay with you, and we will send the others forward for help.”

“I do not feel so tired now,” said the lad. “I am ready.”

Yussuf took the lead again and they set off, walking steadily on straight past the cliff-dwellings, and the ruins by the cave, till they reached the spot in the beautifully-wooded vale where, from far above, they had seen the horsemen pass, little thinking at the time that they were bearing off their strong helps to a journey through the mountains, and all the food.

Here the beaten track curved off to the left, and the traces left by the horses were plain enough to see, for there was a little patch of marshy ground made by a little spring here, and this they had passed, Yussuf eagerly scanning them, and making out that somewhere about twelve horses had crossed here, and there were also the footprints of five or six men.

“If we go this way we may overtake the scoundrels,” said the old lawyer, “but it will not do. Yussuf, I am a man of peace, and I should prove to be a very poor creature in another fight. I had quite enough to last me the rest of my life on board that boat. Here, let’s rest a few hours.”

“No, excellency; we must go on, even if it is slowly. This part of the valley is marshy, and there are fevers caught here. I have been along here twice, and there is a narrow track over that shoulder of the mountain that we can easily follow afoot, though we could not take horses. It is far shorter, too. Can the young effendi walk so far?”

Lawrence declared that he could, for the mountain air gave him strength. So they left the beaten track, to continue along a narrow water-course for a couple of miles, and then rapidly ascend the side of one of the vast masses of cliff, the path being literally a shelf in places not more than a foot wide, with the mountain on their left rising up like a wall, and on their right the rock sank right down to the stream, which gurgled among the masses of stone which had fallen from above, a couple of hundred feet below them and quite out of sight.

“’Pon my word, Yussuf, this is a pretty sort of a place!” panted Mr Burne. “Hang it, man! It is dangerous.”

“There is no danger, effendi, if you do not think of danger.”

“But I do think of danger, sir. Why, bless my heart, sir, there isn’t room for a man to turn round and comfortably blow his nose.”

“There is plenty of room for the feet, effendi,” replied Yussuf; “the path is level, and if you will think of the beautiful rocks, and hills, and listen to the birds singing below there, where the stream is foaming, and the bushes grow amongst the rocks, there is no danger.”

“But I can’t think about the beauty of all these things, Yussuf, my man, and I can only think I am going to turn giddy, and that my feet are about to slip.”

“Why should you, effendi?” replied the Turk gravely. “Is it not given to man to be calm and confident, and to walk bravely on, in such places as this? He can train himself to go through what is dangerous to the timid without risk. Look at the young effendi!” he added in a whisper; “he sees no danger upon the path.”

“Upon my word! Really! Bless my heart! I say, Preston, do you hear how this fellow is talking to me?”

“Yes, I hear,” replied the professor. “He is quite right.”

“Quite right!”

“Certainly. I have several times over felt nervous, both in our climb this morning, and since we have been up here; but I feel now as if I have mastered my timidity, and I do not mind the path half so much as I did.”

“Then I’ve got your share and my own, and—now, just look at that boy. It is absurd.”

“What is absurd?” said the professor quietly.

“Why, to see him walking on like that. Ill! Invalid! He is an impostor.”

The professor smiled.

“I say, is it safe to let him go on like that?”

“So long as he feels no fear. See how confident he is!” said Mr Preston.

Just then Lawrence stopped for the others to overtake him.

“Have you noticed what beautiful white stone this is, Mr Preston?” he said.

He pointed down at the path they were on, for every here and there the rock was worn smooth and shiny by the action of the air and water, perhaps, too, by the footsteps of men for thousands of years, and was almost as white as snow.

“Yes,” said the professor, “I have been making a mental note of it, and wishing I had a geologist’s hammer. You know what it is, I suppose?”

“White stone, of course,” said Mr Burne.

“Fine white marble,” said the professor.

“Nonsense, sir! What! in quantities like this?”

“To be sure.”

“But it would be worth a large fortune in London.”

“Exactly, and it is worth next to nothing here, because it could not be got down to the sea-shore, and the carriage would be enormous.”

“What a pity!” exclaimed the old lawyer. “Dear me! Fine white marble! So it is. What a company one might get up. The Asia Minor Major Marble Quarry Company—eh, Preston?”

“Yes, in hundred-pound shares that would be worth nothing.”

“Humph! I suppose not. Well, never mind. I’d rather have a chicken pie and a loaf of bread now than all the marble in the universe. Let’s get on.”

Their progress was slow, for in spite of all that Yussuf had said they had to exercise a great deal of care, especially as the narrow track rose higher and higher, till they were at a dizzy height above the little stream, whose source they passed just as the sun was getting low; and then their way lay between two steep cliffs; and next round a sunny slope that was dotted with huge walnut-trees, the soil being; evidently deep and moist consequent upon a spring that crossed their path.

The trees were of great girth, but not lofty, and a peculiarity about them was that they were ill-grown, and gnarled and knotted in a way that made them seem as if they were diseased. For every now and then one of them displayed a huge lump or boss, such as is sometimes seen upon elms at home.

“There’s another little fortune there, Burne,” said the professor quietly.

“Nonsense, sir! There isn’t a tree in the lot out of which you could cut a good board. Might do for gun-stocks.”

“My dear Burne,” said the professor, “don’t you know that these large ugly bosses go to Europe to be steamed till they are soft, and then shaved off into leaves as thin almost as coarse brown paper, and then used and polished for all our handsome pianofortes?”

“No,” said Mr Burne shortly, “I didn’t know it, and I didn’t want to know it. I’m starving, and my back is getting bad again. Here, Yussuf, how much farther is it?”

“Two hours’ journey, excellency; but as soon as we reach that gap in the rocks we come to a road that leads directly to the village, and the walking will be easier.”

“Hadn’t we better try and shoot a bird or an animal, and make a fire under those trees, and see if we can find some walnuts? I must eat something. I cannot devour snuff!”

The professor smiled.

“There is nothing to shoot,” he said; “and as to the walnuts, they are very nice after dinner with wine, but for a meal—”

“Here, Lawrence, you are tired out, my boy,” cried Mr Burne interrupting.

“Yes, I am very tired,” said Lawrence, “but I can go on.”

“It is dreary work to rest without food,” said Yussuf, “but it might be better to get on to the spring yonder, and pick out a sheltered place among the rocks, where we could lie down and sleep for a few hours, till the moon rises, and then continue our journey.”

“That’s the plan, Yussuf; agreed nem con,” cried Mr Burne.

“Perhaps it will be best,” said Mr Preston, and they journeyed on for another half hour, till they reached the gap which their guide had pointed out, one which proved to be the embouchure of another ravine, along the bottom of which meandered a rough road that had probably never been repaired since the Romans ruled the land.

“Let us go a little way in,” said Yussuf; “we shall then be sheltered from the wind. It will blow coldly when the sun has set.”

He led the way into a wild and awful-looking chasm, for the shadows were growing deeper, and to the weary and hungry travellers the place had a strangely forbidding look, suggestive of hidden dangers. But for the calm and confident way in which Yussuf marched forward, the others would have hesitated to plunge into a gorge of so weird a character, until the sun had lightened its gloomy depths.

“I think this will do,” said Yussuf, as they turned an angle about a couple of hundred yards from the entrance. “I will climb up here first. These rocks look cave-like and offer shelter. Hist!”

He held up his hand, for a trampling sound seemed to come from the face of the rocks a couple of hundred feet above them, and all involuntarily turned to gaze up at a spot where the shadows were blackest.

All except Yussuf, who gazed straight onward into the ravine.

It was strange. There was quite a precipice up there, and it was impossible for people to be walking. What was more strange, there was the trampling of horses’ feet, and then it struck the professor that they were listening to the echoes of the sounds made by a party some distance in.

“How lucky!” said Mr Burne. “People coming. We shall get something to eat.”

“Hush, effendi!” said Yussuf sternly. “These may not be friends.”

“What?” exclaimed Mr Burne, cocking his gun.

“Yes; that is right, excellencies; look to your arms. If they are friends there is no harm done. They will respect us the more. If they are enemies, we must be prepared.”

“Stop!” said Mr Preston, glancing at Lawrence. “We must hide or run.”

“There is time for neither, effendi,” said Yussuf, taking out his revolver. “They will be upon us in a minute, and to run would be to draw their fire upon us.”

“Run!” exclaimed Mr Burne; “no, sir. As I’m an Englishman I won’t run. If it was Napoleon Bonaparte and his army coming, and these were the Alps, I would not run now, hungry as I am, and I certainly will not go for a set of Turkish ragamuffins or Greeks.”

“Then, stand firm here, excellencies, behind these stones. They are mounted; we are afoot.”

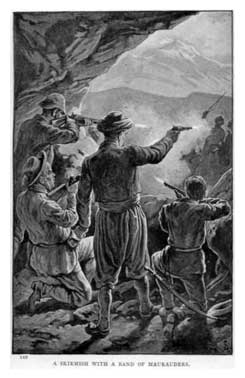

The little party had hardly taken their places in the shadow cast by a rock, when a group of horse and footmen came into sight. They were about fourteen or fifteen in number apparently, some mounted, some afoot, and low down in that deep gorge the darkness was coming on so fast that it was only possible to see that they were roughly clad and carried guns.

They came on at a steady walk, talking loudly, their horses’ hoofs ringing on the stony road, and quite unconscious of anyone being close beside the path they were taking till they were within some forty yards, when a man who was in front suddenly caught sight of the group behind the rocks, checked his horse, uttered a warning cry, and the next moment ample proof was given that they were either enemies or timid travellers, who took the party by the rocks for deadly foes.

For all at once the gloomy gorge was lit by the flashes of pretty well a dozen muskets, the rocks echoed the scattered volley, and magnified it fifty-fold, and then, with a yell, the company came galloping down, to rush past and reach the open slope beyond.

How it all happened neither Mr Burne nor the professor could fully have explained. It must have been the effect of Yussuf’s example, for, as the bullets flew harmlessly over the party’s head, he replied with shot after shot from his revolver, discharging it at the attacking group. As he fired his second shot, Mr Burne’s fowling-piece went off, both barrels almost together, and the professor and Lawrence both fired as the group reached them, and after them, as it passed and went thundering by and down the slope out beyond the entrance to the gorge.

“Load again quickly,” cried the professor; “they may return. There is one poor wretch down.”

His command was obeyed, empty cartridges thrown out and fresh ones inserted; but the trampling of horses’ hoofs was continued, and gradually grew more faint, as the little party descended from their improvised fort. They ran down, for something curious had occurred.

As the band of horsemen charged, their company seemed to divide in two, and the cause appeared to be this:

One of the mounted men was seen to fall from his saddle and hang by the stirrup, when his horse, instead of galloping on, stopped short, and five other horses that were seen to be riderless stopped, after going fifty yards, and cantered back to their companion and huddled round him.

“Why, there’s Ali Baba!” cried Lawrence excitedly, as he ran down and caught his little steed by the bridle.

“And the pack-horses!” cried Mr Burne quite as excitedly, as he followed.

“Enemies, not friends, effendi,” said Yussuf quickly.

For all had seen at once now that they had recovered their lost horses, it being evident that the travellers, by taking the short cut, had got ahead of the marauding band, for such they seemed to be; and they had possibly made the task the easier by halting somewhere on the way to let their horses feed.

But there was another cause for the horses keeping together, and not following those of the strangers in their headlong flight, for, on coming up, the reason for the first one stopping was perfectly plain. Hamed, the pack-horse driver, had been made prisoner, and, poor fellow! secured by having his ankles bound together by a rope which passed beneath the horse’s girths. When the charge had been made he had slipped sidewise, being unable to keep his seat, and gone down beneath his horse, with the result that the docile, well-trained animal stopped at once, and then its comrades had halted and cantered back.

“Is he much hurt, Preston?” said Mr Burne eagerly, as the professor supported the poor fellow, while Yussuf drew out his dagger and cut the rope.

“I cannot say yet. Keep your eyes on the mouth of the gorge, and fire at once if the scoundrels show again.”

“They will not show again, effendi,” said Yussuf. “They are too much scared. That’s better. The horses will stand. They know us now. Take hold of your bridle, Mr Lawrence, and the others will be sure to stay.”

Lawrence obeyed, and rested his piece on the horse’s back, standing beside him and watching the mouth of the defile, while the others carried the injured man to the side and laid him down, the professor taking out his flask which was filled with spirit.

“Yes,” said Yussuf, acquiescing. “It is not a drink for a true believer, but it is a wonderful medicine, effendi.”

So it proved, for soon after a little had been poured down Hamed’s throat the poor fellow opened his eyes and smiled.

“It is your excellencies!” he said in his native tongue; and upon Yussuf questioning him, he told them faintly that he was not much hurt, only a little stunned. That he was seated by the fount, with his horses grazing, when the band of armed men rode up, and one of them struck him over the head with the barrel of his musket, and when he recovered somewhat he found himself a prisoner, with his legs tied as he was found, and the horses led and driven down a narrow defile, out of which they had made their way into a forest of shady trees. Later on they had made a halt for a couple of hours, and then continued their journey, which was brought to an end, as far as he was concerned, by his falling beneath his horse.

“What is to be done now?” said the professor.

“Eat,” exclaimed Mr Burne, “even if we have to fight directly after dinner.”

“The effendi is right,” said Yussuf smiling. “If we go on, we may fall into a trap. If we go back a little way here till we find a suitable spot, the enemy will not dare to come and attack us in the dark. Can you walk, Hamed?”

The poor fellow tried to rise, but his ankles were perfectly numbed, and there was nothing for it but to help him up on one of the horses, and go back farther into the gloomy ravine, which was perfectly black by the time they had found a likely place for their bivouac, where the horses would be safe as well, and this done, one of the packs was taken down from its bearer and a hearty meal made by all, Yussuf eating as he kept guard with Lawrence’s gun, while Hamed was well enough to play his part feebly, as the horses rejoiced in a good feed of barley apiece.