Chapter 5 | Roy Takes His Next Lesson | The Young Castellan

The clock in the little turret which stood out over the gate-way facing Lady Royland’s garden had not done striking six when Roy entered the armoury next morning, to find Ben hard at work fitting the interior of a light helmet with a small leather cap which was apparently well stuffed with wool.

“Morning, Ben,” said the boy. “What’s that for?”

“You, sir.”

“To wear?”

“Of course. Just as well to take care of your face and head when you’re handling swords. You can use it with the visor up or down, ’cording to what we’re doing. You see, I want to learn you how to use a sword like a soldier, and not like a gentleman who never expects to see trouble.”

“Ready?”

“Yes, sir, quite; and first thing ’s morning we’ll begin where we left off, and you shall try to learn that you don’t know how to thrust. Nothing like finding out how bad you are. Then you can begin to see better what you have to learn.”

“Very well,” said Roy, eagerly. “You’ll have to look out now then, Ben, for I mean to learn, and pretty quickly.”

“Oh, yes; you’ll learn quickly enough,” said Ben, placing the helmet upon the table and taking the pair of sticks up from where he had placed them. “But say, Master Roy, I have been working here. Don’t you think the place looks better?”

“I think my father would be proud of the armoury if he could see the weapons,” said Roy, as he looked round. “Everything is splendid.”

The old soldier smiled as he walked from suit to suit of armour, some of which were obsolete, and could only be looked upon as curiosities of the day; but, in addition, there were modern pieces of defensive armour, beautifully made, with carefully cleaned and inlaid headpieces of the newest kind, and of those the old soldier seemed to be especially proud. Then he led the way on to the stands of offensive weapons, which numbered quaint, massive swords of great age, battle-axes, and maces, and so on to modern weapons of the finest steel, with, guns, petronels, and horse-pistols of clumsy construction, but considered perfect then.

“Yes, sir, I’m proud of our weepuns,” said Ben; “but I aren’t a bit proud of the old castle, which seems to be going right away to ruin.”

“That it isn’t,” cried Roy, indignantly. “It has been repaired and repaired, whenever it wanted doing up, again and again.”

“Ah! you’re thinking about roofs and tiles and plaster, my lad. I was thinking about the defences. Such a place as this used to be. Look at the gun-carriages,—haven’t been painted for years, nor the guns cleaned.”

“Well, mix up some paint and brush it on,” said Roy, “and clean up the guns. They can’t be rusty, because they’re brass.”

“Well, not brass exactly, sir,” said the man, thoughtfully. “It’s more of a mixtur’ like; but to a man like me, sir, it’s heart-breaking.”

“What! to see them turn green and like bronze?”

“Oh, I don’t mind that so much, sir; it’s seeing of ’em come down so much, like. Why, there’s them there big guns as stands in the court-yard behind the breastwork.”

“Garden, Ben.”

“Well, garden, sir. Why, there’s actooally ivy and other ’nockshus weeds growing all over ’em.”

“Well, it looks peaceful and nice.”

“Bah! A gun can’t look peaceful and nice. But that aren’t the worst of it, sir. I was along by ’em a bit ago, and, if you’ll believe me, when I put my hand in one, if there warn’t a sharp, hissing noise!”

“A snake? Got in there?”

“Snake, sir? No! I wouldn’t ha’ minded a snake; but there’s no snakes here.”

“There was one, Ben, for I brought it up out of the woods, and kept it in a box for months, till it got away. Then that’s where it is.”

“Nay. It were no snake, sir. It were one of them little blue and yaller tomtit chaps as lays such lots o’ eggs. I fetches a stick, and I was going to shove it in and twist it in the hay and stuff o’ the nest and draw it out.”

“But you didn’t?”

“No, sir, I didn’t; for I says to myself, if Sir Granby and her ladyship like the place to go to ruin, they may let it; and if the two little birds—there was a cock and hen—didn’t bring up twelve of the rummiest little, tiny young uns I ever did see. There they was, all a-sitting in a row along the gun, and it seemed to me so comic for ’em to be there that I bust out a-laughing quite loud.”

“And they all flew away?”

“Nay, sir, they didn’t; they stopped there a-twittering. But if that gun had been loaded, and I’d touched it off with a fire-stick, it would have warmed their toes, eh? But would you clean up the old guns?”

“I don’t see why you shouldn’t, Ben. They’re valuable.”

“Vallerble? I should think they are, sir. And, do you know, I will; for who knows what might happen? They tell me down in the village that there’s trouble uppards, and people gets talking agen the king. Ah! I’d talk ’em if I had my way, and make some of ’em squirm.—Yes, I will tidy things up a bit. Startle some on ’em if we was to fire off a gun or two over the village.”

“They’d burst, Ben. Haven’t been fired for a hundred years, I should say. Those brass guns were made in Queen Elizabeth’s time.”

“Oh, they wouldn’t burst, sir; I shouldn’t be afraid of that.—But this is not learning to thrust, is it?”

“No. Come on,” cried Roy, and he took one of the stout ash rods. “Here, hadn’t I better put on this helmet?”

“Not yet, sir. You can practise thrusting without that. Now then, here I am, sir. All ready for you on my guard. Now, thrust.”

Ben dropped into an easy position, with his legs a little bent, one foot advanced, his left hand behind him, and his stick held diagonally across his breast.

Roy imitated him, dropping into the same position.

“Where shall I stab you?” he cried.

“Just wherever you like, sir,—if you can.”

The boy made a quick dart forward with his stick, and it passed by his teacher, who parried with the slightest movement of his wrist.

“I said thrust, sir.”

“Well, I did thrust.”

“That wasn’t a thrust, sir; that was only a poke. It wouldn’t have gone through a man’s coat, let alone his skin. Now, again!”

The boy made another push forward with his stick, which was also parried.

“Nay, that won’t do, my lad; so let’s get to something better. Now, I’m going to thrust at you right in the chest. Enemies don’t tell you where they’re going to hit you, but I’m going to tell you. Now, look out!”

Roy prepared to guard the thrust, but the point of the old man’s stick struck him sharply in the chest, and he winced a little, but smiled.

“Now, sir, you do that, but harder.”

Roy obeyed, but failed dismally.

“Of course,” said Ben. “Now that’s because you didn’t try the right way, sir. Don’t poke at a man, but throw your arm right back till you get your hand level with your shoulder, and sword and arm just in a line. Then thrust right out, and let your body follow your arm,—then you get some strength into it. Now, once more.”

Roy followed his teacher’s instructions.

“Better—ever so much, sir. Now again—good; again—good. You’ll soon do it. Now, can’t you see what a lot of weight you get into a thrust like that? One of your pokes would have done nothing. One like that last would have sent your blade through a man. Now again.”

Roy was now fully upon his mettle, and he tried hard to acquire some portion of the old soldier’s skill, till his arm ached, and Ben cried “Halt!” and began to chat about the old-fashioned armour.

“Lots of it was too clumsy, sir. Strong men were regularly loaded down; and I’ve thought for a long time that all a man wants is a steel cap and steel gloves. All the rest he ought to be able to do with his sword.”

“But you can’t ward off bullets with a sword, Ben,” said Roy.

“No, sir; nor you can’t ward ’em off with armour. They find out the jyntes, if they don’t go through.”

“Would that suit of half-armour be much too big for me, Ben?” said Roy, pausing before a bronzed ornamental set of defensive weapons, which had evidently been the work of some Italian artist.

“No, sir, I shouldn’t think it would. You see that was made for a small man, and you’re a big lad. If you were to put that on, and used a bit o’ stuffing here and there, you wouldn’t be so much amiss. It’s in fine condition, too, with its leather lining, and that’s all as lissome and good as when it was first made.”

“I should like to try that on some day, Ben,” said the boy, eagerly examining the handsome suit.

“Well, I don’t see why not, sir. You’d look fine in that. Wants three or four white ostrich feathers in the little gilt holder of the helmet. White uns would look well with that dark armour. Looks just like copper, don’t it?”

“How long would it take to put it on?” said Roy.

“Hour, sir; and you’d want some high buff boots to wear with it.”

“An hour?” said Roy. “There wouldn’t be time before breakfast.”

“No, sir. But I tell you what—I’ve only cleaned and polished and iled the straps. If you feels as if you’d like to put it on, I’ll go over it well, and see to the buckles and studs: shall I?”

“Yes, do, Ben.”

“That I will, sir. And I say, if, when you’re ready, I was to saddle one of the horses proper, and you was to mount and her ladyship see you, she’d be sorry as ever she wanted you to be a statesman.”

Roy shook his head dubiously.

“Oh, but she would, sir. Man looks grand in his armour and feathers.”

“But I’m only a boy,” said Roy, sadly.

“Who’s to know that when you’re in armour and your visor down, sir? A suit of armour like that, and you on a grand horse, would make a man of you. It’s fine, and no mistake.”

“But you were sneering at armour a little while ago, Ben,” said Roy.

“For fighting in, sir, but not for show. You see, there’s something about armour and feathers and flags that gets hold of people, and a soldier’s a man who likes to look well. I’m an old un now, but I wouldn’t say no to a good new uniform, with a bit o’ colour in it; but if you want me to fight, I don’t want to be all plates and things like a lobster, and not able to move. I want to be free to use my arms. Right enough for show, sir, and make a regiment look handsome; but fighting’s like gardening,—want to take your coat off when you go to work.”

“But you will get that armour ready, Ben?”

“Course I will, sir. On’y too glad to see you take a liking to a bit o’ armour and a sword. Now, then, what do you say to beginning again?”

“I’m ready,” said Roy, but with a longing look at the armour.

“Then you shall just put that helmet on, and have the visor down. You won’t be able to see so well, but it will save your face from an accidental cut.”

He placed the helmet on the boy’s head, adjusted the cheek straps, and drew back.

“Find it heavy, sir?”

“Rather! Feels as if it would topple off as soon as I begin to move.”

“But it won’t, sir. The leather cap inside will stop that. Now, then, if you please, we’ll begin. I’m going to cut at you slowly and softly, and you’ve got to guard yourself, and then turn off. I shall be very slow, but after a bit I shall cut like lightning, and before I’ve done I shan’t be no more able to hit you than you’re able now to hit me.”

Roy said nothing, and the man began cutting at him to right and to left, upward from the same direction and downward, as if bent upon cleaving his shoulders; and for every cut Ben showed him how to make the proper guard, holding his weapon so that the stroke should glance off, and laying especial weight upon the necessity for catching the blow aimed upon the forte of the blade toward the hilt, and not upon the faible near the point.

Then came the turn of the head, and the horizontal and down right cuts were, after further instruction, received so that they, too, glanced off. Roy gaining more and more confidence at every stroke. But that helmet was an utter nuisance, and half buried the wearer.

“I’m beginning to think you’re right, Ben, about the armour,” said the lad, at last.

“Yes, ’tis a bit awkward, sir; but you’ll get used to it. If you can defend yourself well with that on, why, of course, you can without. Now, then, suppose, for a change, you have a cut at me.”

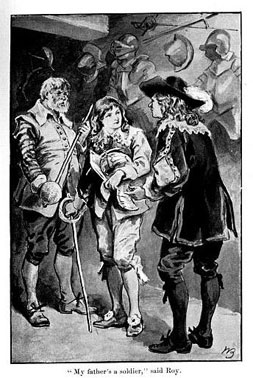

“Why, what tomfoolery is this?” said a highly-pitched voice; and Roy tried to snatch off his helmet as he caught sight of the secretary standing in the door-way looking on.

But the helmet would not come off easily, and, after a tug or two, Roy was fain to turn to the old soldier.

“Here,” he said, hastily, “unfasten this, Ben, quick!”

“Yes, sir; but I don’t see as you’ve any call to be in such a hurry. You’ve a right to learn to use a sword if you like. Only the strap fastened over this stud, and there you are.”

Red-faced and annoyed, Roy faced the secretary, who had walked slowly into the armoury, to stand looking about him with a sneer of contempt upon his lip.

“Only practising a little sword-play, sir,” said the boy, as soon as his head was relieved.

“Sword-play! Is there no other kind of play a boy like you can take to? What do you want with sword-play?”

“My father’s a soldier,” said Roy.

“Yes; but you are not going to be a fighting man, sir; and, behindhand as you are with your studies, I think you might try a little more to do your instructor credit, and not waste time with one of the servants in such a barbaric pursuit as this. Lady Royland is waiting breakfast. You had better come at once.”

Feeling humbled and abashed before the old soldier, Roy followed the secretary without a word, and they entered the breakfast-room together, Lady Royland looking up pale and disturbed, and, upon seeing her son’s face, exclaiming—

“Why, Roy, how hot and tired you look! Have you been running?”

The secretary laughed contemptuously.

“No, mother; practising fencing with Ben.”

“Oh, Roy!” cried his mother, reproachfully; “what can you want with fencing? My dear boy, pray think more of your books.”

Master Pawson gave the lad a peculiar look, and Roy felt as if he should like to kick out under the table so viciously that the sneering smile might give place to a contraction expressing pain.

But Roy did not speak, and the breakfast went on.