Chapter 35 | How the Castle Came Back To Its Owner | The Young Castellan

Shrieks and cries for help mingled with the blast of a trumpet and the trampling of feet, as Roy hurried on his clothes, his first thought being not to follow his father, but to reach his mother’s room, though, in the confusion of brain from which he suffered, he felt that he could explain nothing about the cause of the explosion. All he could think was that by some means the Cavaliers must have contrived to gain access to the powder-magazine. But how?

That was a mystery.

While he hurriedly dressed, he could hear orders being given, and the guns which had been brought in and planted beneath the gate-way being dragged into the middle of the court, and planted where they would command the terrible  breach in the castle defences; for, by a flickering light, which was now rising, falling, and always gathering in intensity, Roy could see that a large portion of the eastern side of the building was blown down, leaving a tremendous gap. The stabling, corridor, hospital-room, and servants’ and other adjacent chambers, were gone; and as he gazed across from his open window, the light suddenly blazed up, brightly illuminating the ruin, and showing the garrison busily preparing for their defence.

breach in the castle defences; for, by a flickering light, which was now rising, falling, and always gathering in intensity, Roy could see that a large portion of the eastern side of the building was blown down, leaving a tremendous gap. The stabling, corridor, hospital-room, and servants’ and other adjacent chambers, were gone; and as he gazed across from his open window, the light suddenly blazed up, brightly illuminating the ruin, and showing the garrison busily preparing for their defence.

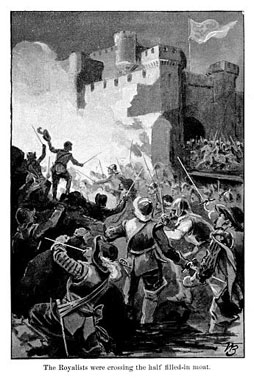

It was time; for, as Roy paused for a few moments, hesitating to leave the scene which fascinated him by its weird horror, the Royalists were crossing the half-filled-in moat, scrambling, wading, helping each other, and cheering madly. There was no formation; they were forced to come on straggling as they could, but a fierce enthusiasm filled their breasts, and they literally swarmed into the ruins, and climbed here and there among the flames and smoke.

Fully expecting to be stopped, Roy opened his door; but the sentry had been summoned with those from the towers and ramparts to defend the great gap, and Roy passed on to his mother’s room, entered without stopping to knock, to see her surrounded by the women-servants at the window, their faces lit up by the flames rising brighter and brighter from the ruins.

Lady Royland did not hear her son enter, but turned and caught his hands as he ran to her.

“Roy!” she cried, wildly. “What does this mean?”

“Our turn at last, mother,” he said, wild with excitement. “Look,—look at them, the Royalists; they’ve blown down that side, and father is there with two hundred Cavaliers!”

“Roy!” she cried, hysterically.

“Yes,” continued the lad, as he forced himself to the front, and gazed out; “look, mother; nothing stops them. Hurrah! More and more, and—”

The roar of one of the guns from the middle of the court drowned his words, and there was another roar, but the effect was little. The guns were discharged point-blank at the storming party climbing on the ruins; but they were scattered like skirmishers, and the gun-fire did not check them in the least. To Roy it only seemed that they dashed in more furiously, swarming, by the light of the blazing ruins, like bees; and before the guns could be reloaded, the Cavaliers were upon the defenders of the place, and a desperate hand-to-hand fight commenced.

Roy turned excitedly to his mother.

“Stop here; keep the women with you, and don’t go near the window; there may be firing;” and, even as he spoke, shots began to ring out.

“Stop! Where are you going?” cried Lady Royland, clinging to him.

“To release our men, and help my father,” said Roy.

Lady Royland’s hands fell to her sides, and the boy darted out of the room and along the corridor, full of the idea that had flashed into his brain.

Away to the end he ran unchallenged, turned to the right, and without meeting a soul, reached the north-east tower, listening to the shouting and clashing of swords in the court as the desperate fight went on, his way lit by the glare from the flames in spite of the dense, heavy smoke and the choking fumes of exploded gunpowder which rolled along the passage.

With his heart beating wildly for fear he should be too late, Roy dashed down the spiral staircase to the basement, and the next minute he reached the door of the lower hall, which formed the men’s prison-chamber.

The sentries were gone, and he thrust back the bolts and turned the ponderous key.

“Ben! Corporal! Donny! All of you—quick!”

“Ay, ay, sir. You’re only just in time, for we’re most smothered. What does it all mean?”

“Don’t talk! Follow me—guard-room. Enemy all in the court.”

He led the way back, the men literally staggering after him, half suffocated as they had been by the fumes of the powder, the explosion having been so near their prison. But they revived moment by moment in the pure air, and growing excited by the sounds that reached them from the court-yard, they followed on along the lower passages till they reached the crypt of the south-west tower, passed on to the stairway at the base of the gate tower, and ascended unchallenged to the great gate-way, where Roy dashed into the untenanted guard-room, and the men rapidly armed themselves with weapons from the racks.

“Ready?” said Roy, in a whisper.

“Yes,” came in a deep, excited growl.

“Back, then,” cried Roy, “and we’ll attack them in the rear.”

He ranged his men in the shadow, the combatants being wildly engaged amid a blaze of light, which prevented the movements of Roy’s little party being seen; and he was about to lead them back through the great corridor to where they could dash out suddenly and make their diversion in the rear, when Ben suddenly laid his hand upon the boy’s arm, and ran to one of the narrow slits of windows in the guard-room.

“Trampling of horses,” he whispered, as he peered out, the glow upward now lighting the other side of the moat. “General’s men coming back, sir. Take us up into the portcullis-room, and we must defend that and keep it and the furnace-chamber to the death. They must not come in.”

Roy grasped the position, knowing well enough that as soon as the defenders knew of the return of their friends, they would admit them, and the Cavaliers would suffer defeat.

Giving the word, he dashed up the spiral followed by his men, and as they stood ready to defend the place to the last, and keep bridge and portcullis as they were, he stepped up into the window and thrust out his head, to see dimly a body of about fifty horsemen, who galloped up to the edge of the moat.

“Halt!” shouted their leader. “No good: impossible. We must ride round, dismount, and join Royland through the breach. Forward!”

“Halt!” shrieked Roy with all his force in his cry, and then in a voice he did not know as his own, he yelled out, “Royland! Royland! God save the king!”

The effect was electrical. His words were answered by a loud “hurrah!”

Roy looked back from the window-splay.

“Friends!” he panted. “Ben, up with you, and lower the bridge;” and as the old sergeant sprang to the staircase, followed by five more, the others seized the capstan-bars and began to hoist the portcullis; while, sword in hand, Roy stood on the narrow stair, determined to die sooner than an enemy should pass.

But the next minute the bridge was down, with the defenders in ignorance of what was going on; the first knowledge they had of what was to come being given by the thunder of the horses’ hoofs, and a deafening cheer as the Cavaliers dashed in.

That charge decided the fight, for in less than five minutes, in spite of the officer’s desperate valour, the defenders broke and fled, to take refuge in corridor and chamber, from whence they could fire upon their enemies.

But, half-mad now with excitement, and flushed by the certainty of victory, the Cavaliers, headed by Sir Granby Royland, went in pursuit, chasing the Parliamentary party through the passages, never giving them time to combine, capturing knot after knot, and forcibly driving the rest below, where, feeling that all was over, their captain ended the carnage by offering to surrender. Then the triumphant Cavaliers gathered in the court-yard, waving hat and sword in the bright light of the burning building, and raising the echoes with their shouts.

It was about this time that Roy, followed by his little party, sought out his father, to find him at last, busy, like the careful soldier he was, stationing men at the towers, and then arranging for a proper defence of the great gap in the castle side, though temporarily it was now well defended by a line of flames that no man could pass.

Roy gazed in dismay at the blackened, blood-stained man, bleeding from two fresh wounds, and was ready to wonder whether this was the gallant, handsome cavalier who had left the castle to go on the king’s service so short a time before.

“Ah! my brave, true boy!” cried Sir Granby, catching him by the shoulders; “old Martlet tells me how you led them to open a way for our friends. It was the work of a good soldier, Roy. You’ll be a general yet. What do you say?” he continued, with a laugh; “as I am now? There, everything is safe for the present. Where is your mother? Am I fit to see her, though?”

Roy said nothing, but clung to the hand that grasped his; and a few minutes later Sir Granby was locked in his wife’s arms.

By this time a strong party had been formed to attack the flames; and as there was an abundance of water from the moat, the day broke upon the quenching of the last burst of fire, and revealed a sad scene of desolation, the side of the castle on the east being one long hollow range of burnt-out buildings, saving the hospital-room, which had escaped, with a wide gap of tottering and piled-up ruins where the magazine had exploded, hurling great masses of stone into the court-yard and the moat.

The fire mastered, Sir Granby commenced forming a rough breastwork of the stones, using for the most part all that could be dragged from the moat, the Cavaliers wading in and working like labourers to strengthen the breach, which towards evening began to look strong with the rough platforms made for the enemy’s three heavy guns. The work was so far completed none too soon, for just at dusk a body of men was seen approaching in the distance, and General Hepburn soon after appeared, to find that he had been outwitted in turn, and that a long siege would be necessary before he could hope to be master of the place again.

That long siege followed; and at last, weakened by loss of men and reduced from want of food, the Cavaliers were unable to combat the terrible assault delivered by the little army that had gradually been gathered about the walls, and the castle fell once more into the hands of the Parliamentarians, who were generous enough to treat the gallant defenders with the honours they deserved.

“But they would never have taken it, Roy,” said Sir Granby, “if that gap had not been blown out. I’d give something to know how it occurred. Could it have been done by that villain Pawson out of despite?”

It was long before the truth was known, when, after years of exile with his wife and son, Sir Granby Royland returned to take possession of his ruined castle and estate. For the young king had ridden into London, and his father’s defenders were being made welcome to their homes.

It happened during the excavating that went on, while the masons were at work digging out and cleaning all the stones which would be available for rebuilding the shattered side, that Sir Granby wrote a letter to Captain Roy Royland, the young officer in the body-guard of his majesty, King Charles the Second. The letter was full of congratulations to the young man on his promotion, and towards the end Sir Granby said—

“I have kept your mother away from the work going on, for I have been afraid that the digging would mean the turning over of plenty of sad mementoes of that terrible time; but, strangely enough, these discoveries have been confined to two. You remember how we wondered that Master Palgrave Pawson never showed himself again, to take possession of the place he schemed to win, and how often we wondered what became of poor old Jenk. Well, in one day, Roy, the men came upon the poor old man crouched up in a corner of the vault, close to the magazine. From what we could judge, the powder must have exerted its force upward, for several of the places where the stones were cleared out were almost uninjured, and this was especially so where they found old Jenk. The poor fellow must have been striking his blow against his master’s enemies, for, when the stones were removed, he lay there with a lantern and a coil of slow-match beneath, showing what his object must have been in going down to the magazine. The other discovery was that of the remains of my scoundrel of a secretary. They came upon him crushed beneath the stones which fell upon the east rampart, where, perhaps you remember, there was a little shelter for the guard. Master Pawson must have been on the ramparts that night, and perished in the explosion.

“Come home soon, Roy, my lad; we want to see you again. They ought to give you leave of absence now, and by the time you get here, I hope to have the old garden restored, and looking something like itself once more. The building will, however, take another year.

“Roy, my boy, they bury soldiers, as you know, generally where they fall; and your mother and I thought that if poor old Jenk could have chosen his resting-place, it might have been where we laid him. As you remember, the old sun-dial in the middle of the court was levelled by the explosion. It has been restored to its place, and it is beneath the stones that your grandfather’s faithful old servant lies at rest.

“Ben Martlet begs me to remember him to you, and says it will do his eyes good to see you again; and your mother, who writes to you as well, says you must come now. My wounds worry me a good deal at times, and I don’t feel so young as I was; but there, as your mother says, what does it matter now we can rest in peace? for we live again in another, our own son—Roy.”