Chapter 19 | The Young Castellan Speaks Out | The Young Castellan

The day passed anxiously on, and it was getting well towards sunset, but there was no sign of the farm men, neither did the enemy appear in sight. Farmer Raynes appealed to Roy again and again for permission to go in search of his people; but, anxious as the young castellan was for news, he could not risk losing one of the strongest and most dependable men he had.

“They may get here yet, Master Raynes,” he said; “and I’d give anything to see them; but I’d rather lose the swords of all ten than lose yours.”

“Mean that, Master Roy?” said the bluff farmer, looking at him searchingly.

“Mean it? Of course!”

“Thank ye, sir. Then I’ll stop; but I feel as if I’d failed you at a pinch by only coming alone.”

“Then don’t think so again,” said Roy, “but help me all you can with the men, for I’m afraid we are going to have a hard fight to save the place.”

“Oh, we’ll save it, sir. Don’t you fear about that,” said Raynes; and he went away to join Ben and talk about the chances of the party reaching the castle.

In the guard-room the matter was also eagerly discussed; for the help of ten sturdy lads was badly needed, as all knew. Sam Donny, who was rather inflated by the success which had attended him and his companions that day, gave it as his opinion that the labourers had been taken prisoners solely because they had not thought to go down and crawl as he and his companions had that day.

Roy had hurriedly snatched a couple of meals, and tried to cheer his mother about their prospects, but to his surprise, he found that she was ready to try and console him about the loss of ten good strong men.

“But do you think they have thought better of it, and are afraid to come in?” said Master Pawson at their hurried dinner.

“No, I do not,” said Roy. “I will not insult the poor fellows by thinking they could be such curs.”

“Quite right, Roy,” said the secretary, eagerly. “I was wrong. I’m afraid I understand books better than I do men. Yes; they must have been taken prisoners, I’m afraid.”

The evening meal had just been commenced when there was a shout from one of the towers.

Roy hurried out, full of hope that the ten men had been descried; but he was soon undeceived, for on mounting to his favourite post of observation it was to see that a long line of horseman was approaching from the direction of Dendry Town, the orange sunlight making their arms glitter as they came gently on, spreading out to a great length, till at last Ben gave it as his opinion that there were at least five hundred men.

Hardly had he come to this conclusion when another body of men was descried approaching from the east, and in the face of this danger the drawbridge was raised, the portcullis lowered, and a trumpet-call summoned the men to the guns.

“They mean it then to-night, Ben,” said Roy, whose heart now beat fast, and he turned to the old soldier, who, with a grim look of pride in his face, was affixing the silken flag to the rope, ready for hauling up when the enemy drew near.

Before Ben could reply, to Roy’s surprise, Lady Royland came up the spiral stairs, and stepped out upon the leads, followed by Master Pawson, who looked sallow of aspect, but perfectly calm.

“You here, mother?”

“Yes, my boy; and why should I not be? I am visiting all the towers to thank the men for their brave conduct in coming here for our defence. How many do you muster now?”

“Thirty-six only,” replied Roy.

“Well, thirty-six brave men are better than five hundred cowards.—How many men do you think there are coming against us, Martlet?”

“Seven or eight hundred, my lady.”

“And will they attack this evening?”

“No, my lady; they don’t come to attack strongholds with mounted men. They’re coming to call upon us to throw open the gates and surrender the place; and this is the answer, I think, my lady, is it not?” and he pointed to the flag.

“Yes, Martlet,” said Lady Royland, flushing; “that is our answer to such an insolent demand.”

She turned and left the tower, attended by Master Pawson, and Roy remained there watching the long line of mounted men approaching with their arms glittering in the light. “Seven or eight hundred,” he said, half aloud, “against thirty-six.”

“Haven’t counted the guns, Master Roy, nor the moat, nor the towers, nor all the other strong things we have. Pah! what’s a regiment of horse against a place like this? But they know, and they’re only coming to bully us, sir.”

“I hope you are right, Ben,” said the lad, seriously; and he waited for the approach of the men till they were halted about a couple of hundred yards away from the tower on which he stood, forming up in squadrons; and after a time an officer, bearing a little white flag, advanced, followed at a short distance by a couple of troopers. Roy’s heart beat fast, for he felt that a crucial time had come.

“You’ll have to go down, Master Roy; and we must lower the bridge for you to go out and meet him and hear what he has to say.”

“Must I, Ben?”

“Of course, sir; and, if you give the order, the corporal and I will come behind you as your guard.”

“And suppose, when the bridge is down, the others make a rush?”

“Flag o’ truce, sir. But if they did, our guns would sweep ’em away.”

“And what about us, Ben?”

“Well, sir,” said the old fellow, drily, “we should be swep’ away too.”

“I say, Ben!”

“Yes, sir, sounds nasty; but soldiers has to take their chance o’ that sort o’ thing, and look at the honour and glory of it all. Ready, sir?”

“Yes,” said Roy, in a husky voice; and a minute later he stood with the two martial-looking figures behind, and the drawbridge slowly descended in front. The two guns were manned, a small guard of three was behind each, and the port-fires sparkled and shot tiny little flashes of fire as if eager to burst out into flame.

Just then, as Roy was watching the heads of the three mounted men coming slowly forward, and, as the end of the bridge sank, seeing their chests, the horses’ heads, and finally their legs come into sight, Ben leaned towards him, and said, in a whisper—

“They don’t know how young you are, sir. Let ’em hear my dear old colonel speaking with your lips.”

“Yes,” said Roy, huskily; “but what am I to say, Ben?”

“You don’t want no telling, sir. Advance now.”

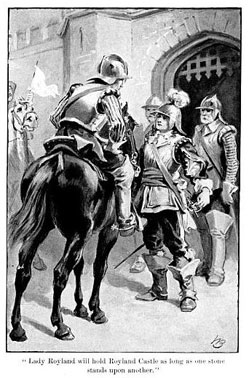

The officer had halted his men about fifty yards from the outer gate, and rode forward a few paces before drawing rein and waiting for some action on the part of those he had come to see; and he looked rather surprised as they stepped forward now, crossed the bridge, and advanced to meet him. For he had not anticipated to find such careful preparations, nor to see the personage who came to meet him in so perfect a military trim, and supported by a couple of soldiers whose bearing was regular to a degree.

The officer was a grim, stern, hard-looking, middle-aged man, and his garb and breastplate were of the commonest and plainest description. He seemed to glance with something like contempt at the elegantly fluted and embossed armour the boy was wearing, and, above all, at the gay sash Lady Royland’s loving hands had fastened across his breast. But his attention was keen as he scanned the soldierly bearing of Ben and the corporal, and a feeling of envy filled his breast as he compared them with his own rough following. Perhaps he would not have thought so much if he had seen the rest of the garrison, but they were too distant.

Roy saluted the officer, and drew a deep breath as he tried to string up his nerves till they were stretched like a bow. For Ben’s words had gone home, and he felt fully how big a part he had to play.

The officer saluted in response in a quick, abrupt manner, and said shortly:

“I come from the general commanding the army here in the west, to demand that you give up peaceable possession of this castle, once the property of the rebel, Sir Granby Royland, who is now in arms against the Parliament of England.”

Roy gave a start at the word “rebel,” and felt the hot blood rise to his cheeks. That insult acted like a spur. The nervous trepidation had gone, for there was no room for it alongside of the anger which flashed through him. Ben was right: the boy knew what to say. It was there ready, and only wanted bringing out.

“Look here, sir!” he cried, sharply; “you come here under a flag of truce to deliver a message, but that does not warrant insolence.”

“Insolence?” said the officer, sternly.

“Yes. I hold no parley with a man who dares to call my father, King Charles’s faithful servant, a rebel.”

“Then go back, boy, and send your mother to make the arrangement for handing over the keys of the castle,” said the officer, with a smile of contempt, “for I suppose the Dame Royland is here.”

“Lady Royland is here, sir; and I, her son, tell you to inform your rebel general that we here recognise no authority but that of his majesty the king, and that we consider it a piece of insolent braggadocio for him to send such a demand.”

“Indeed!” said the officer, laughing. “Well crowed, young game-cock!”

“Yes,” muttered Ben; “and you mind his spurs.”

“Have you anything more to say?” cried Roy.

“Yes; a good deal, my boy, and I will not notice your young, hot-blooded words. You have allowed your men to perform an act this morning that may mean serious consequences for you.”

“I do not understand your meaning, sir.”

“Yes, you do, boy,” said the officer, sternly. “You allowed your men to fire upon a picket of our cavalry.”

“Of course. You allowed your cavalry, as you term them, to try and ride down six unarmed men on their way to the castle, and I gave orders for them to be stopped, and they were stopped.”

“I have no time to argue these things with you, sir. I have only this to say: if you give up the keys to me at once, your people can disperse unharmed to their homes, and Dame Royland and her son can depart with such personal effects as she desires, to go wherever she pleases, and an escort will be provided for her protection.”

“And, if she declines this offer, sir, as my father’s steward of his estates and possessions?”

“Your father has neither estate nor possessions now, my boy; he is a proclaimed rebel. If this kindly offer is refused, and you are both so weak and vain as to resist, the place will be battered down and left in ruins, while the sufferings and slaughter of your people will be at your door. Now, sir, briefly, what message am I to take back to the commanding officer?”

“God save the king!” cried Roy, warmly.

“That is no answer, sir—only the vain cry of an enthusiastic, misled boy. What am I to say to the general in chief?”

“That Lady Royland will hold Royland Castle in the king’s name as long as one stone stands upon another, and she has a brave following to fight.”

The officer raised his hand in salute, turned his horse and rode back, while Roy stood there with his heart throbbing as he watched the three figures depart, and wondered whether it was really he who had spoken, or all this scene in the deepening evening were part of a feverish dream.

He was brought back to the present by the deep gruff voice of Ben.

“There, sir,” he said, with a look of pride at the boy in whose training he had had so large a share, “I knew you could.”

At the same moment Roy glanced at the corporal, who smiled and saluted him proudly.

“I only wish, sir,” he said, “that the colonel had been here.”

Roy turned to recross the bridge, feeling as if, in spite of all, this was part of a dream, when something on high began to flutter over the great gate tower, and glancing up, it was to see there in front, gazing down at them as she leaned forward in one of the embrasures, Lady Royland.

“What is it to be, Roy?” she cried, as he came closer. “Peace or war?”

“War!” he replied, sternly; and the sound seemed to be whispered in many tones through the great archway as the portcullis fell with its heavy clang and the drawbridge began to rise.