Chapter 6 | The Great White Horse | The King's Sons

Encouraged by these words of the monk and the smiles and praises of the Queen, Alfred made rapid progress, which, oddly enough, grew quicker still from the way in which Bald and his brothers ridiculed him and laughed at his attempts, for their gibes angered him, but only made him work the harder, and with results which Swythe told the Queen were wonderful. Six long weary weeks had passed away since Ethelwulf had gone with his little army against the Danes, and only once had news been received, so that Queen Osburga’s face grew whiter, thinner, and more sad day by day, till one evening when, after a long hard day’s work with the monk, the pair went up to the top of the highest hill near to watch for the appearance of a messenger. Swythe could see no sign of anything.

“There is no news,” he said sadly. “Let us go back. The Queen is waiting to hear what we have found.”

“There is news,” cried the boy excitedly. “I can see the points of spears right away there in the valley. Look, the sun shines upon them and makes them glitter.”

“Yes, I see now,” cried Swythe excitedly. “Quick, let’s try and run, boy. The Danes! The Danes! We must get the Queen away into the woods so as to be safe.”

“Why not stop in the big house, and shut up every window and door? We must fight. You can fight, Father Swythe?”

“I, my boy?” said the monk sadly. “Yes, with my tongue. No, I am only a man of peace. All we can do is to fly for our lives. There are not twenty strong fighting-men, Fred, my son, and those who are coming against us must, from the spears and shining iron caps with wings like the Norsemen wear, be quite a thousand. Quick! You can go faster than I. Run on first and warn the good Queen that it is time to fly!”

Alfred nodded his head quickly and started off to run; but at that moment it struck him that it would be foolish to run and give the alarm without being sure. The monk had declared the force to be the enemy, but the boy wished to see for himself, and, darting sidewise, he ran down the hill, bearing to his right, till by stooping he could keep under cover of the gorse-bushes and approach quite near to the coming army.

It was a daring thing to do, for it might have ended in being made a prisoner without the chance of giving the alarm; but the brave act turned out to be quite wise, for when at last the boy had drawn near to the great body of armed men and crouched lower till he found a place through which he could peer cautiously, he sprang to his feet with a shout of joy.

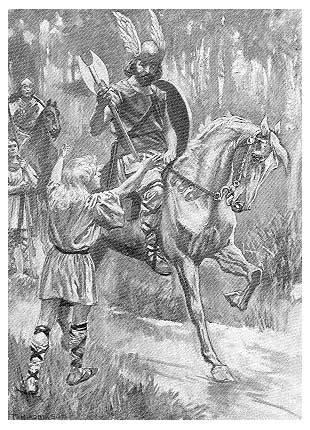

For there in front rode his father, King Ethelwulf, mounted upon a sturdy horse, but so changed that he hardly knew him, for he was wearing a Danish helmet ornamented with a pair of grey gull’s wings, half-opened and pointed back, while in his left hand he carried a Danish shield painted with a black raven, and in his right was a shining double battle-axe.

Alfred’s cry was answered by a shout from the men, and Ethelwulf rode forward to meet his son, who grasped his extended hands and sprang up to sit in front of him upon the horse.

“Your mother—Osburga?” said the King hoarsely.

“Ill, father, because you do not come,” cried the boy excitedly.

“Hah! Then she will soon be well,” said the King, with a sigh of content. “Yonder is plump little Swythe coming to welcome me, I see,” he continued; “but where are your brothers?”

“I don’t know, father,” replied the boy, innocently enough. “They have not come back from hunting, I think.”

King Ethelwulf frowned, but said no more then, contenting himself with pressing forward to give his hand to Swythe, who had followed the boy as soon as he saw him change his course; and soon after the King’s heart was gladdened by seeing Osburga with her train of women and serfs coming to meet them, answering the Saxon soldiers’ cheers. But Bald, Bert, and Red had even then not come back from the chase.

That night the King told of the great victory which he had at last gained over the Danish invaders, who had been defeated with great slaughter near Farringdon, and it was in memory of that victory that the King returned to the battlefield with his men on a peaceful errand, and that was to use the spade instead of the battle-axe and sword, while they cut down through the green turf on one hill-side, right down to the clean, white, glistening chalk, after the lines had been marked out and the shape cleverly designed, working for weeks and weeks till there, on the slope they had carved out a huge white horse over a hundred yards in length—the Great White Horse of the Berkshire downs, which has remained as if galloping along until this day.

Year after year the scouring of that horse, as it is called, takes place, when men go and clear out the brown earth that has crumbled through frost and rain into the ditch-like lines which mark the horse’s shape on the green hill-side, and make it stand out white and clear as ever.

No one will think it strange after what has been told that the youngest of those four boys grew up under Swythe’s teaching wise and learned, and as brave as, or braver than, either of his three brothers, who, when at last King Ethelwulf died, succeeded in turn to be King of England. They each sat on the throne—Ethelbald, Ethelbert, and Ethelred; but their reigns were short, for in twenty years they too had passed away, to be succeeded by the strong, brave, and learned man who drove the Danish’ invaders finally from the shores of England, or forced them to become peaceful workers of the soil. He was the brave warrior who never knew what it was to be conquered, but tried again and again till the enemy fled before him and his gallant men.

Old chronicles tell many stories of his deeds—stories that have grown old and old—and they tell too that the studious boy’s teacher Swythe became Bishop of Winchester and was called a saint, while old writers have worked up a legend about the rain christening the apples on Saint Swithin’s Day, and when it does, keeping on sprinkling them for forty days more; but, like many other stories, that one is not at all true, as any young reader may find out by watching the weather year by year.

But that does not matter to us, who have to deal with Alfred the Little, and who willingly agree that as he grew up he was worthily given the name of Alfred the Great.