Chapter 3 | Fred is Left Behind | The King's Sons

Time went on, and King Ethelwulf gathered and led off to the assistance of Jarl Cerda all the fighting-men he could assemble, as a wounded messenger had arrived from that noble, asking the King for more help, for he was sore pressed by the enemy.

The Danes, he sent word, were in great force, and more and more of their war-galleys kept coming up the river, the occupants slaying and destroying wherever they landed.

It was an anxious time for Queen Osburga, whose eyes often looked red as if she had been weeping, while her cheeks grew white and thin, and she shut herself up a great deal, so that no one should see her.

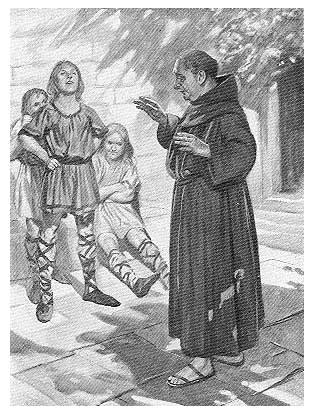

The men-folk had nearly all departed from the place, and there was no one to exercise authority, so, as soon as the four boys had recovered from their disappointment at not being allowed to go with the little army their father led, they began to look upon it as a free and jovial time in which they could do whatever pleased them most, and this they did to such an extent that poor Swythe’s face became full of lines, and after trying in vain to make his pupils continue their studies, and putting up with a great amount of disobedience on their part, he began to reproach them in his mild way. He was one of the gentlest and most amiable of men, but the wilfulness of the boys had at length compelled him to protest.

“It seems so shocking,” he said, rather piteously. “I only beg and pray of you all, now that the King is at the war and our dear lady the Queen in such sorrow and trouble, to try your best to get on with your lessons, so that the King may feel proud of his sons when he returns. Ethelbald laughs and mocks at me; Ethelbert says he will not study; Ethelred follows his example; and Alfred, of whom I expected better things, has just told me he does not mind a bit what I say, and that he will do just as he likes.”

“And so he shall!” said Bald boldly. “That is, he shall do as I like. Father has gone to fight the Danes, and while he’s away, as I am the eldest, I shall act in his place, and shall expect everyone to obey me as if I were King.”

“Oh, no, no, no,” cried Swythe, looking shocked. “Our dear lady Osburga is Queen, and everyone must obey her.”

“Do not speak of that to me!” cried Ethelbald. “She is only a woman, and cannot manage the men. Why, if father should be killed—”

“Which Heaven forbid!” cried Swythe, with a look of horror on his face. “Oh, dear me, Ethelbald, what a thing for you to say! Shocking, my dear boy.”

“I don’t want him to be killed,” cried Bald. “Of course not. But if he should be killed I shall become King directly, and I shall order everybody to do what I like, and no one will dare to say a word. The first thing I shall do,” he continued, with a laugh, “will be to send old Swythe away, so that there will be no more learning Latin, boys, and no crabbing fingers up to hold tens.”

The three brothers said something with a shout which in those days answered to “Hooray!” and then Alfred, who had shouted the loudest, being the youngest and ready to think brother Bald’s words very brave and fine, suddenly began to feel uncomfortable; for he had a certain amount of fear of the monk his master, and felt a kind of shrinking from rebelling against his authority. He glanced sidewise at Father Swythe and saw that his eyes glimmered in a peculiar way as if water was rising in them. Directly afterwards his heart felt a little sore, and a sense of shame began to trouble him, for there was no mistake: Father Swythe’s eyes were wet and his voice sounded hoarse and strange as he said sadly:

“You would not send me away, Ethelbald? I have always tried to do my duty to the young sons of my lord the King and have tried to make them grow into scholarly princes fit to rule the land.”

“Bah! We do not want to be scholarly!” cried Bald scornfully. “We want to learn to be brave soldiers, so that we can go forth and beat the Danes.”

“Yes,” said the monk sadly; “but, my boys, the warrior who’s a scholar as well is more brave and noble and merciful, and his name is one that lives longer in the land. Ah, well, you have made me very sad. I had hoped that I had done something to make the sons of my dear lady the Queen love me; but if they do not it would be better perhaps that I should go back to my cell at the old abbey, where I could be happy with my parchments and my pens.”

The old monk sighed and turned away; he appeared to have received a shock which had broken his heart.

The three elder boys were laughing and joking about the matter, and suddenly Ethelbald cried out:

“Come along, boys! Bows and arrows. I saw a roebuck feeding outside the oak wood. Here, we’ll take spears with us too to-day. Let old Swythe teach the swineherds’ boys to read Latin instead of minding the little pigs hunting for acorns.”

“No spears left!” said Bert.

“The men took them all when they went away!” said Red.

“Then let’s go without!” said Bald.

Alfred said nothing; he was watching the monk going slowly and sadly away, and somehow the little figure did not look comic to him then, even if it was short and plump and round.

“Where’s Fred?” cried Bald the next minute, when the boys were getting their bows and quivers.

His brothers could not tell him where Alfred was; so after a few moments pause, Ethelbald said:

“Never mind: let’s go without him. Hers too young and weak to do what we do. Let him stay behind and learn Latin with old Swythe.”

“He did go out after him,” said Bert.

“Yes, I saw him. I remember now,” cried Red.

His last words were almost smothered by his eldest brother, who raised to his lips a curling cow-horn tipped with a copper mouthpiece and strengthened with a ring at the head end. He proceeded to blow into it, but failed to produce anything more huntsman-like than a kind of bray such as might be uttered by a jackass suffering from a sore-throat.

But it was good enough to send all the dogs about the place frantic, and away the three boys went, followed by a pack of hounds, some of which would have been as ready to tackle wolf or boar as to dash after the lordly stag or the big-eyed, prong-horned, graceful roes of which there were many about the forest lands which surrounded the King’s home.

Alfred, from one of the upper windows, saw them go away in triumph and longed to join them; but he did not do so, for there was sorrow in his heart, and for the first time in his young life he had begun to think deeply about the words spoken by his brother and those uttered so sadly and reproachfully by the simple-hearted, gentle monk.