Chapter 1 | Sons of the King | The King's Sons

The sun shone down hotly on the hill-side, and that hill was one of a range of smooth rolling downs that ought to have been called ups and downs, from the way they seemed to rise and fall like the sea on a fine calm day.

Not quite, for at such a time the sea looks as blue as the sky above it, while here on this particular hot day, though the sky was as blue as a sapphire stone, the hills were of a beautiful soft green, the grass being short and soft, and as velvety as if Nature had been all over it regularly with her own particular mowing-machine.

But the only mowing that had been done to that grass was by the cropping teeth of the many flocks of sheep whose fleeces dotted the downs with soft white where they nibbled away, watched by the shepherds in their long smock frocks with turn-down collars and pleatings and gatherings on breast and back, and slit up at the sides from the bottom so as to give the men’s legs room to move freely when they ran after a restive sheep to hook him with the long crook they carried and bring him kicking and struggling by hook or by crook to the grass.

It was just over a thousand years ago, and, in spite of all the changes fashion has made, plenty of shepherds and farm labourers still wear the simple old Saxon dress then worn by King Ethelwulf’s serfs, though without the girdle worn then.

There were four boys on the steepest slope of that hill-side—four fair-haired, sun-browned, hearty-looking boys—and they wore smock frocks, belted in at the waist, of fine, soft, woollen material, woven out of the fleeces of the sheep; for they were King’s sons, the sons of the King whose flocks were feeding on the hill-side in Berkshire, where he had his Court.

It was as peaceful there as it was soft and beautiful; for though news came from time to time of the cruel acts of the fierce Norsemen who had come across the sea in their great row and sailing galleys full of fighting-men, they were far away from the King’s home, so that Queen Osburga felt no anxiety about her boys being out on the downs at play, enjoying themselves and growing strong. This she loved to see; though, being a very learned woman herself in days when noble people thought no shame to have to say: “I cannot read or write,” she sighed to find how very little her four sons cared for such things as gave her delight.

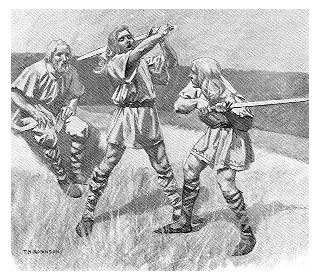

They all loved to be out in the open air along with Cerda, the Saxon jarl, one of the King’s chief fighting-men, who urged them to learn how to use the broadsword. After setting one of the men to make swords for the boys—not of hard cutting steel, but of good tough ash-wood—and then matching them two against two, he would sit and roar with laughter at the blows they gave and took.

“Well done! At him again!” he cried. “Another wound; but it will not bleed.”

It was Cerda, too, who had bows and arrows made for the boys, whilst King Ethelwulf would look on, sometimes smiling and sometimes sighing, for he cared nothing for these things.

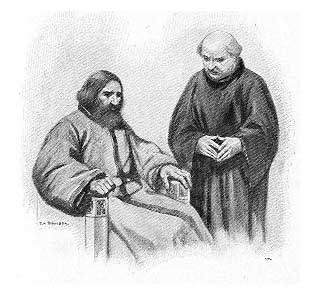

“But we must have fighting-men, Swythe,” he said, to a little plump, rosy-looking monk in a long gown held tightly to his waist by a knotted rope, which cut in a good way, for the monk was very fat.

“Oh, but fighting’s bad, sir, very bad,” said the monk, passing one of his hands round and round over his shining, closely-shaven crown.

“Very bad,” said King Ethelwulf. “I hate it; but you know what the Danes have done to so many of your holy house—killing, burning, and carrying off everything that is good.”

The monk screwed up his face, shook his head, and sighed, while the rosy little man looked so droll that the King smiled.

“Look here, Swythe,” he said, “suppose a horde of the savage wretches came up here to plunder my pleasant home, what would you do?”

“Hah!” said the monk. “I am a man of peace, sir; I should run away.”

“And leave the Queen and my boys and me to be killed or taken prisoners?”

“Hah! No,” said the monk. “I couldn’t do that. I’m afraid I should take the biggest staff I could lift—or a sword—or an axe—and—and if either of the wretches tried to touch our good Queen or either of my dear boys I should hit him as hard as ever I could.”

“With the club?” said the King.

“No; I should strike him down with the axe, sir.”

“But you might kill him, Swythe.”

“And if I did, sir,” said the little monk fiercely, “it would be a good thing too; for these Norsemen are wicked pagans, come to kill and slay.”

“You see, we must have fighting-men, Swythe,” said the King; and then he turned to the Queen, who was listening to what they said.

“Hah! yes, sir,” said the monk, with a sigh. “I suppose we must; and it does my heart good to see how clever the young Princes are with sword and bow; but they spend too much time learning to fight. If they would only spend half the time learning with me!”

“Yes, it would be good,” said Queen Osburga sadly.

“But they don’t,” continued the monk. “There’s only young Alured—Alfred, as you call him—who will learn at all, and he is nearly as idle as his brothers.”

“You cannot say that they are idle,” said the Queen, smiling gently.

“Well, perhaps not idle, my daughter,” said the monk, shaking his head, “because they do work hard to learn what Jarl Cerda teaches them.”

“Yes,” said King Ethelwulf, “they are apt to learn how to fight; but you must make them learned, as kings should be, so as to rule wisely and well when the Danes have killed me and they are called upon to reign.”

“The Danes never shall kill you, sir,” cried the little monk fiercely, “so long as I can stand in their way.”

The little group now separated, for the King and Queen had many duties to perform in connection with state affairs, and the little monk had to prepare the lessons for the boys.

And that’s how matters were on that bright sunny day when King Ethelwulf’s sons lay out on the steep hill-side—Bald, Bert, Red, and Fred—four as crisp and tongue-tripping names as four bright Saxon English boys could own, but each with the addition of Athel or Ethel before, except the youngest, in whose name it shortened into Al; and these were their titles, because each was a Prince.