Chapter 7 | Life on the Veldt | Diamond Dyke

The task of finding the emptied ostrich nest proved harder than they expected; but their ride across the barren plain was made interesting by the sight of a herd of gnus and a couple of the beautiful black antelope, with their long, gracefully curved, sharp horns. Just before reaching the nest, too, they had the rather unusual sight, in their part, of half-a-dozen giraffes, which went off in their awkward, lumbering trot toward the north.

At last, though, the nest was reached, the scattered eggs gathered into the net, and heedless of these chinking together a little, as they hung between them, they cantered on.

“Won’t do them any good shaking them up so, will it?” said Dyke.

“I’ve given up all idea of setting these,” said Emson. “I should say it would be very doubtful whether they would hatch, and we want a little change in the way of feeding, old fellow. We’ll see which are addled, and which are not.”

Tanta Sal was at the door as they rode up, and her face expanded largely, especially about the eyes and mouth, at the sight of the eggs.

“I say, look at Tant,” said Dyke merrily. “Did you ever see such a face?”

“Never,” replied Emson quietly. “She’s not beautiful from our point of view.”

“Beautiful!”

“Tastes differ, old chap,” said Emson. “No doubt Jack thought her very nice-looking. English people admire small mouths and little waists. It is very evident that the Kaffirs do not; and I don’t see why a small mouth should be more beautiful than a large one.”

“And there isn’t so much of it,” cried Dyke.

“Certainly not, and it is not so useful. No: Tant is not handsome, but she can cook, and I don’t believe that Venus could have fetched water from the spring in two buckets half so well.”

“Don’t suppose she could, or made fires either,” said Dyke, laughing.

“Very good, then, little un. Tant is quite good-looking enough for us.—Hi! there, old girl, take these and keep them cool. Cook one for dinner.”

The woman nodded, took the net, swung it over her back, and the next minute the creamy-white eggs were seen reposing on the dark skin.

After seeing to the horses, Dyke made some remark to his brother about wanting his corn too, and he went quietly round to the back, where Tant was busy over the fire, preparing one of the eggs by cooking it au naturel, not boiling in a saucepan, but making the thick shell itself do duty for one.

She looked up and showed her teeth as Dyke came in sight, and then went on with her work, which was that of stirring the egg, whose treatment was very simple. She had chipped a little hole in one end, big enough to admit a stick, and had placed the other end deep down in the glowing dry cake ashes, squatting down on her heels on one side of the fire, while Jack sat in a similar position on the other, watching his wife as she kept on stirring the egg with the piece of wood.

“Oh there you are, Jack,” said Dyke; “we’ve shot a big lion.”

“Baas kill?”

“Yes. You’re coming with us to skin it this evening?”

The Kaffir shook his head, and then lowered it upon one hand, making a piteous grimace.

“Jack sick, bad,” he said.

“Jack no sick bad,” cried Tanta, leaping up angrily.

As she spoke, she raised one broad black foot, and gave her husband a sharp thrust in the ribs, with the result that he rolled over and then jumped up furiously to retaliate.

“Ah, would you!” cried Dyke; and the dog, which had followed him, began to growl. “Yes, you hit her, and I’ll set Duke at you,” cried Dyke. “Can’t you see he’s ashamed?”

Jack growled fiercely, and his wife reseated herself upon her heels, and went on stirring the egg again, laughing merrily the while.

“No sick bad,” she said; and then wanting to say something more, she rattled off a series of words, all oom and click, for Jack’s benefit, the Kaffir listening the while.

The egg was soon after declared to be done, and formed a very satisfactory omelette-like addition to the hard biltong and mealie cake which formed the ostrich-farmers’ dinner.

“I’d a deal rather we’d shot an antelope, Joe,” said Dyke, as he ground away at the biltong, that popular South African delicacy, formed by cutting fresh meat into long strips, and drying them in the sun before the flesh has time to go bad—a capital plan in a torrid country, where decomposition is rapid and salt none too plentiful; but it has its drawbacks, and is best suited to the taste of those who appreciate the chewing of leather with a superlatively high flavour of game.

“Yes, it is time we had some fresh meat, old chap,” said Emson good-humouredly. “After that slice of luck with the birds, we’ll try for some guinea-fowl or a springbok in the morning.”

“I wish we had a river nearer where we could fish,” said Dyke, as he worked away at the dried meat.

“Yes, it would be handy, if we could catch any fish; but we usen’t to get a great many—not enough to live on—in the old days at home.”

“Not often,” said Dyke. “I say, it is tough.”

“Well, yes. A well-beaten-out piece would not make a bad shoe sole, little un. But about that fishing? It would take a great many of those sticklebacks you always would fish for with a worm to make a dish.”

“Well, they used to bite, and that’s more than your carp would, Joe. Why, you only used to catch about one a month.”

“But, then, look at the size. One did make a dish.”

“Yes, of only head and bones. Ugh! I’d rather eat biltong.”

Emson laughed good-humouredly.

“Well,” he said, “we can’t go fishing without we make a hundred miles’ journey, so we can’t get fish. How would a lion steak eat?”

“Worse than a cut out of the poor old goblin’s breast. But, I say, are we to go and skin that old savage to-night?”

“I’ll go with Jack, and do it, if you’re tired.”

“That you won’t,” cried Dyke. “But, I say, Jack’s bad sick he says.”

“Yes, I suppose so. He generally is now, when we want him to work. We’ve spoiled Master Jack by feeding him too well; and if it wasn’t for Tanta Sal, Master Jack would have to go upon his travels. That woman’s a treasure, little un. She’s a capital cook; and what a wonderful thing it is that it comes so natural to a woman, whether she’s white or black, to like washing shirts. Do you know, I believe that Tanta Sal would take to starching and ironing if she had a chance. Have any more?”

“No: done,” said Dyke, wiping his knife carefully, and returning it to the sheath he wore in his belt.

“Then let’s go and have a look at the chickens. Why, the other day I felt as if I could open all the pens and say to the birds, ‘There, be off with you, for you’re no good.’”

“But now you’re going to have another good try.”

“Yes; and we must give them greater liberty, and try to let them live in a more natural way.”

“And that means always hunting them and driving them back to the pens.”

“We shan’t mind that if they all turn out healthy,” said Emson. “Come along.”

“Wait till I call Tant,” said Dyke; and he went out to the back to summon the Kaffir woman, who came in smiling, cleared away, and then proceeded to feed her lord; Duke, the dog, waiting for his turn, and not being forgotten.

It was like playing at keeping bantams in Brobdingnag, Dyke said, as they entered the pens pretty well provided with food for the birds, and going from enclosure to enclosure, armed each with a stout stick, necessitated by the manners and customs of their charge. For though it was plain sailing enough scattering out food for the young birds, which stalked about looking very solemn and stupid, the full-grown and elderly, especially the cocks, displayed a desire for more, to which “glutton” would be far too mild a term to apply; while the goblin’s successor, as king of the farm, seemed to have become so puffed up with pride at his succession to the throne, that the stick had to be applied several times in response to his insatiable and aggressive demands.

But at last the feeding was done, the hens in attendance on the nest of eggs visited, where all seemed satisfactory, and then the horses were saddled, and Jack and Duke summoned.

The latter dashed up instantly; but Jack made no reply.

“Yes, he is spoiled,” said Emson. “It has always seemed to be so much less trouble to saddle our own horses than to see that he did it properly; but we ought to have made him do it, little un.”

“Of course we ought,” said Dyke. “It isn’t too late to begin now?”

“I’m afraid it is,” said Emson.—“Here! Hi! Jack,” he shouted; and the dog supplemented the cry by running toward the house, barking loudly, with the result that the Kaffir woman came out, saw at a glance what was wanted, and turned back.

The next minute there was a scuffling noise heard behind the place, accompanied by angry protesting voices, speaking loudly in the Kaffir tongue.

Then all at once Jack appeared, carrying three assegais, and holding himself up with a great deal of savage dignity; but as he approached he was struck on the back of the head by a bone. He turned back  angrily, but ducked down to avoid a dry cake of fuel, and ended by running to avoid further missiles, with his dignity all gone, for Tanta Sal’s grinning face peeped round the corner, and she shouted: “Jack bad sick, baas. All eat—seep.”

angrily, but ducked down to avoid a dry cake of fuel, and ended by running to avoid further missiles, with his dignity all gone, for Tanta Sal’s grinning face peeped round the corner, and she shouted: “Jack bad sick, baas. All eat—seep.”

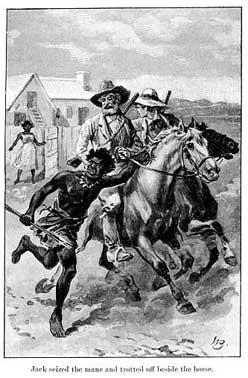

“Yes; that’s what’s the matter, Jack,” said Emson, shaking his head at him. “Now take hold of the horse’s mane, and I’ll give you a good digestive run.”

There was no help for it. Jack seized the mane and trotted off beside the horse, while a derisive shout came from behind the house, and Tanta’s grinning face re-appeared.

This was too much for Jack, who turned to shake his assegais at her: the movement was unpropitious, for he stumbled and fell, but gathered himself up, caught up to the horse, and trotted on again, keeping on in the most untiring way, till a flight of carrion birds was sighted, hovering about the granite boulders, and perching here and there, as if ready for the banquet to come.

Duke charged forward at this, and the birds scattered, but did not go far; while the dog’s approach started half-a-dozen jackals from among the bushes to which they had retired, and they now began scurrying over the plain. “I wonder how they find out that there’s anything dead, Joe,” said Dyke; “we did not see a single jackal or bird this morning.”

“Eyesight,” said Emson quietly. “The vultures are sailing about on high, and one sees the dead animal; then other vultures see him making for it, and follow.”

“And the jackals see the vultures, and follow too?”

“That seems to be the way, old fellow. Anyhow, they always manage to find out where there’s anything to eat.”

“I say, don’t he look big?” said Dyke, as the carcass of the dead lion lay now well in sight.

“Yes; he’s one of the finest I have seen. You ought to get the teeth out of his head, little un; they’d do to save up for your museum.”

“I will,” said Dyke.

The next minute they had dismounted, and were removing the horses’ bridles to let them pick off the green shoots of the bushes. The rifles had been laid down, and Duke had gone snuffing about among the rocks, while Jack was proceeding to sharpen the edge of one of his assegais, when the dog suddenly gave tongue. There was a furious roar, the horses pressed up together, and from close at hand a lion, evidently the companion of that lying dead, sprang out and bounded away, soon placing itself out of shot.

“Ought to have been with us this morning,” said Dyke, as he called back the dog.

“Couldn’t have done better if we had had him,” said Emson, quietly rolling up his sleeves, an example followed by the boy.

“Think that one will come back again?” was the next remark.

“Not while we are here,” was Emson’s reply; and then, as the evening was drawing on, he set to work helping Jack, who was cleverly running the point and edge of his assegai through the skin from the lion’s chin to tail, and then inside each leg right down to the toes.

A busy time ensued, resulting in the heavy skin being removed uninjured, and rolled up and packed across Emson’s horse.

“You’ll have to leave the teeth till another day,” said Emson, as the stars began to peep out faintly, and they trotted homeward; but before they had left the carcass a couple of hundred yards, a snapping, snarling, and howling made Duke stop short and look inquiringly up at his masters, as much as to say:

“Are you going to let them do that?” But at a word he followed on obediently, and the noise increased.

“Won’t be much lion left by to-morrow morning, Joe,” said Dyke.

“No, boy. Africa is well scavengered, what with the jackals, birds, and flies. But we’d better get that skin well under cover somewhere when we are back.”

“Why? Think the jackals will follow, and try and drag it away?”

“No; I was feeling sure that the other lion would.”

Emson was right, for Dyke was awakened that night by the alarm of the horses and oxen, who gave pretty good evidence of the huge cat’s being near, but a couple of shots from Emson’s gun rang out, and the animals settled down quietly once again, there being no further disturbance that night on the lonely farm.