Chapter 6 | Lions at Home | Diamond Dyke

Fortune smiled her brightest upon Joseph Emson when they first came up the country, travelling for months in their wagon, till Kopfontein, with its never-failing spring in the granite chasm, was settled upon as being a capital place to carry out the idea of the ostrich-farm. Then the rough house was run up, and in course of time pens and other enclosures made, and by very slow degrees stocked with the gigantic birds, principally by help of Kaffir servants; Jack showing himself to be very clever in finding nests of eggs, but afterwards proving lazy and indifferent, excusing himself on the plea that “Baas got all eggs. No more. All gone.”

It seemed to be a capital idea, and promised plenty of success, for at first the feathers they obtained from the Kaffirs sold well, making capital prices when sent down to Cape Town. Then the supply from the native hunters began to fail; and when at last the young farmers had plumes to sell of their own raising, prices had gone down terribly, and Emson saw plainly enough that he was losing by his venture.

Then he began to lose his birds by accident, by the destructive propensities of the goblin and a vicious old hen or two; and lastly, some kind of epidemic, which they dubbed ostrich chicken-pox, carried the young birds off wholesale.

Then Dyke began to be damped, and grew dull, and soon his brother became low-spirited too, and for a whole year matters had gone on from bad to worse; Emson often asking himself whether it was not time to make a fresh start, but always coming to the same frame of mind that it was too soon to be beaten yet, and keeping a firm upper lip in the presence of his brother.

The morning after the finding of the ostrich’s nest, they started again, taking the net, and keeping a keen lookout in the hope of discovering another.

“There’s no reason why we should not,” said Emson. “I’ve been too easy with Jack; he has not disturbed the birds around for months.”

“I think we can find the nest again,” said Dyke.

“Why not? We’ll find it by the footmarks, if we cannot any other way. But I think I can ride straight to it.”

They kept a sharp lookout, but no ostrich sprang up in the distance and sped away like the wind. About six miles from home, though, something else was seen lying right out on the plain, to which Dyke pointed.

“A bird?” cried Emson. “Yes, I see it. No; a beast. Why, Dyke, old chap, there are two of them. What shall we do? Creep in and try a shot, or let them go off?”

“I should try a shot,” said the boy excitedly. “Why, one is a big-maned fellow.”

“Then perhaps we had better let them alone.”

“What! to come and pull down one of the oxen. No: let’s have a shot at them.”

“Very well,” said Emson quietly; “but see that you have a couple of bullets in your rifle. Make sure.”

He set the example by opening the breech of his piece, and carefully examining the cartridges before replacing them.

“All right,” he cried. “Now, look here, Dyke. Be ready and smart, if the brutes turn upon us to charge. Sit fast, and give Breezy his head then. No lion would overtake him. Only you must be prepared for a sharp wheel round, for if the brutes come on with a roar, your cob will spin about like a teetotum.”

But no satisfactory shot was obtained, for when they were about a quarter of a mile away, a big, dark-maned lion rose to his feet, stood staring at them for nearly a minute, and then started off at a canter, closely followed by its companion.

Dyke looked sharply round at his brother, as if to say, “Come on!” but Emson shook his head.

“Not to-day, old chap,” he cried. “We’re too busy. It would mean, too, a long gallop, tiring our horses before we could get a shot, and then we should not be in good condition for aiming.”

“Oh, but, Joe, I daresay that is the wretch that killed the white ox, and he is hanging about after another.”

“To be sure: I forgot that,” cried Emson excitedly. “Come on. But steady: we can’t lose sight of them, so let’s canter, and follow till they stand at bay or sneak into the bushes.”

That was more to Dyke’s taste, and side by side they followed the two lions, as the great tawny-looking beasts cantered over the plain, their heads down, tails drooping, and looking, as Dyke said, wonderfully like a couple of great cats sneaking off after being found out stealing cream.

There was no need to be silent, and Dyke kept on shouting remarks to his brother as they cantered on over the dry bush and sand.

“I don’t think much of lions, after all, Joe,” he said; “they’re not half kings of beasts like you see in pictures and read of in books.”

“You haven’t seen one in a rage, old fellow,” said Emson good-humouredly.

“I don’t believe they’d be anything much if they were,” said Dyke contemptuously. “They always seem to me to be creeping and sneaking about like a cat after a mouse. Now look at those great strong things going off like that, as soon as they see us, instead of roaring at us and driving us away.”

“Smell powder, perhaps, and are afraid of the guns.”

“Well, but if they did, that isn’t being brave as a lion, Joe. Why, when they killed the white ox, there were four of them, and they did it in the dark. I don’t believe when you shot that the bullet went near either of the brutes.”

“No, but we scared them off.”

“They killed the poor old bullock first, though.”

“Well, didn’t that give you a good idea of a lion’s strength; the poor beast’s neck was broken.”

“Let’s show them to-day that we are stronger, and break their necks,” said Dyke. “Look out: they’re gone.” For the two great beasts suddenly plunged into a patch of broken ground, where great blocks of granite stood up from among the bushes, and sheltered them with larger growth.

It was the only hiding-place in sight, and for this the lions had made, and now disappeared.

“We shan’t get a shot at them now, old chap,” cried Emson; “they lie as snug as rats among those bushes. We want old Duke here.”

“Oh, don’t give up,” cried Dyke. “I know that place well; it’s where I found the aardvark, and the bushes are quite open. I am sure we can see them.”

“Well, as you’re so set on it, we’ll try; but mind this, no riding in—nothing rash, you know.”

“Oh, I’ll take care,” cried Dyke. “I shan’t get hurt. You only have to ride right at them, and they’ll run.”

“I don’t know so much about that, old cocksure; but mind this, horses are horses, and I don’t want you to get Breezy clawed.”

“And I don’t want to get him clawed—do I, old merry legs?” cried the boy, bending forward to pat his nag’s neck. “Sooner get scratched myself, wouldn’t I, eh?”

The little horse tossed up its head and shook its mane, and then taking his master’s caress and words to mean a call upon him for fresh effort, he dashed off, and had to be checked.

“Steady, steady, Dyke, boy,” cried Emson; “do you hear?”

“Please sir, it wasn’t me,” replied the boy merrily. “It was him.”

“No nonsense!” cried Emson sternly. “Steady! This is not play.”

Dyke glanced once at his brother’s face as he rode up, and saw that it looked hard, earnest, and firm.

“All right, Joe,” he said quietly; “I will mind.”

The next minute they had cantered gently up to the patch, which was only about an acre in extent, and the bushes so thin and scattered that they could see nearly across where the lions had entered.

But there was no sign of the cunning beasts.

“Look here, Joe; you ride round that way, and I’ll go this; then we are sure to see them.”

“Capital plan,” said Emson sarcastically. “Bravo, general! weaken your forces by one-half, and then if I see them I can’t fire for fear of hitting you, and you can’t fire for fear of hitting me. Try again, clever one.”

“Oh, all right, you try,” said Dyke, in an offended tone.

“Ride round with me, then, either five yards in front or five behind. Will you go first?”

“No, you go,” said Dyke distantly.

“Come along, then. Keep a sharp lookout, and if you get a good chance at the shoulder—fire. Not without.”

“Very well,” said Dyke shortly, “but you see if they don’t sneak out and gallop away on the other side.”

“They won’t leave cover if they can help it,” said Emson; and his words proved true, for as they rode slowly round with finger on trigger, scanning the openings, the cunning brutes glided in and out among the great boulders, and crawled through the bushes, so that not a glimpse of them could be obtained.

“There!” cried Dyke, after they had ridden round twice. “I knew it. While we were talking on one side, they’ve crept out on the other and gone off! They’re miles away now.”

“Exactly!” said Emson; “and that’s why the horses are so uneasy. I say, little un, you don’t get on so fast as I should like with your hunting knowledge. Look at Breezy.”

Dyke glanced at his cob, and the little horse showed plainly enough by its movements that whatever might be its master’s opinion, it was feeling convinced that the lions were pretty close at hand.

“Well, what shall we do—ride through?”

“No,” said Emson decidedly, “that would be inviting a charge. I’m afraid we must separate, or we shall never got a shot. As we ride round one side, they creep along on the other.”

“Did you see them?”

“No, but look there.”

Dyke looked where his brother pointed, and saw plainly marked in the soft sand the footprints of the lions.

“Well, let’s separate, then,” said the boy eagerly. “I’ll mind and not shoot your way, if you’ll take care not to hit me.”

“Very good: we’ll try, then; but be careful not to fire unless you get a good sure chance. Look here; this will be the best plan. One of us must sit fast here while the other rides round.”

“But the one who stops will get the best chance, for the game will be driven towards him. Who’s to stop?”

Emson thrust his hand into his pocket, and drew it out again clenched.

“Something or nothing?” he cried.

“Nothing,” said Dyke sharply.

“Nothing. Right. Your chance,” said Emson.

“Then I’ll stay here?”

“Very well then; be ready. I shall ride ahead, and the lions will sneak round till they find you are here, and then they’ll either go right across, or break cover and gallop off. There’s every chance for a shot. Right forward in the shoulder, mind.”

“Won’t charge me, will they?”

“Not unless they’re wounded,” replied Emson.—“Ready?”

“Yes.”

Emson rode slowly off, and as he went he kept on crying “Here!” at every half-dozen yards or so, giving his brother a good idea of his position and that of the lions too.

Meanwhile Dyke, with his heart beginning to beat heavily, sat facing in the other direction, both barrels of his rifled piece cocked and pointed forward, nostrils distended like those of his horse, and, also like the animal, with every sense on the alert.

“Here—here—here,” came from beyond him, and gradually working more and more to the left, while Dyke felt a great deal more respect for the prowess and daring of lions than he did half an hour before.

The stillness, broken only by his brother’s recurring cry, repeated with such regularity, seemed awful, and the deep low sigh uttered by Breezy sounded quite startling; but there was nothing else—no sound of the powerful cats coming cautiously round, winding in and out among the rocks and bushes, and not a twig was stirred.

“Here—here—here,” kept coming, and Dyke sat gripping the saddle tightly with his knees, feeling a curious quiver pass into him from the horse’s excited nerves, as the swift little beast stood gazing before it at the ragged shrubs, ready to spring away on the slightest sign of danger. The rein lay upon its neck, and its ears were cocked right forward, while Dyke’s double barrel was held ready to fire to right or left of those warning ears at the first chance.

There was the clump on the boy’s left, the open ground of the veldt on his right, and the sun glancing down and making the leaves of the trees hot; but still there was nothing but the regular “Here—here—here,” uttered in Emson’s deep bass.

“They’re gone,” said Dyke to himself, with a peculiar sense of relief, which made his breath come more freely. “They would have been here by now. I’ll shout to Joe.”

But he did not. For at that moment there was the faintest of faint rustles about a dozen yards in front. One of the thin bushes grew gradually darker, and Dyke had a glimpse of a patch of rough hair raised  above the leaves. Then Breezy started violently, and in an instant two lions started up.

above the leaves. Then Breezy started violently, and in an instant two lions started up.

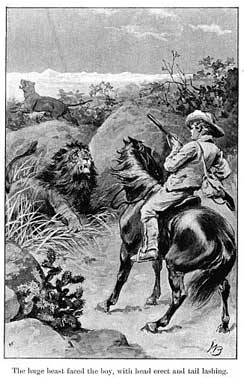

“How!—Haugh!” was roared out. The maneless lion bounded out of the bushes, and went away over the sand in a series of tremendous leaps, while the companion, a huge beast with darkly-tipped mane, leaped as if to follow, but stopped and faced the boy, with head erect and tail lashing from side to side, while the horse stood paralysed with fear, its legs far apart, as if to bear the coming charge, and every nerve and muscle on the quiver.

Dyke sat motionless during those brief moments, knowing that he ought to fire, but feeling as if he were suffering from nightmare, till the majestic beast before him gave vent to a tremendous roar, turned, and bounded away.

Then Dyke’s power of action came back. Quick as a flash, his piece was to his shoulder, and he fired; but the lion bounded onward, hidden for the time by the smoke; yet as it cleared away, the boy had another clear view of the beast end on, and fired once more.

At this there was a savage snarl; the lion made a bound sidewise, and then swung round as if to charge back at its assailant, when Breezy tore off at full speed, but had not gone fifty yards before another shot rang out, and Dyke looked round to see his brother dismounted and kneeling on the sand, while the lion was trailing itself along with its hind-quarters paralysed.

In another minute Emson had remounted and ridden up to the dangerous beast; there was another report from close quarters, and the lion rolled over and straightened itself out.

“Dead?” cried Dyke excitedly, as he mastered Breezy’s objections, and rode up.

“Yes; he’ll kill no more of our oxen, old chap,” cried his brother. “Well done, little un! You stopped him splendidly. That last shot of yours brought him up for me to finish.”

“Think I hit him, then?”

“Think?” said Emson, laughing. “You can easily prove it. Your bullet must have hit him end on. Mine were on his left flank.”

“He is dead, isn’t he?” said Dyke dubious.

“As dead as he can well be,” said Emson, dismounting, and throwing his rein over his horse’s head. “Yes; here we are. Your bullet caught him half-way up the back here; one of mine hit him in the side, and here’s the other right through the left shoulder-blade. That means finis. But that shot of yours regularly paralysed him behind. Your lion, little un, and that skin will do for your museum. It’s a beauty.”

“But you killed him,” said the boy modestly.

“Put him out of his misery, that’s all. He is a splendid fellow, though. But he won’t run away now, little un.—Let’s get on.”

“But his skin?” said Dyke eagerly.

“Too hard a job now, Dyke, under this sun. We’ll come over this evening with Jack, and strip that off. Now for the eggs.”