Chapter 7 | A Life's Eclipse

In those few joyous moments the darkness became light, dazzling light, to John Grange; misery, despair, the blank life before him, had dropped away, and the future spread out in a vista wherein hope shone brightly, and all was illumined by the sweet love of a true-hearted woman.

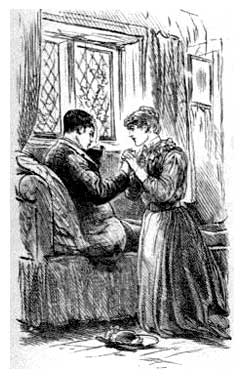

He would have been less than man if he had not drawn the half-shrinking, half-yielding figure to his heart, and held Mary tightly there as, amidst tears and sobs, she confessed how she had long felt that he loved her, but doubted herself the reality of the new sensation which had made her pleased to see him, while when she met him as they spoke something seemed to urge her to avoid him, and look hard, distant, and cold. Then the terrible misfortune had come, and she knew the truth; the bud grew and had opened, and she trembled lest any one should divine her secret, till she knew that he was to go away believing that she might care for Daniel Barnett; in suffering and mental pain, needing all that those who cared for him could do to soften his pitiable case; and at last, believing that she alone could send him away hopeful and patient to bear his awful infirmity, she had cast off all reserve and come to say good-bye.

“And you will not think the less of me?” she whispered appealingly.

“Think the less of you!” he cried proudly; “how can you ask that? Mary, you send me  away happy. I shall go patient and hopeful, believing that the doctors can and will give me back my sight, and ready to wait till I may come back to you, my own love—for I do love you, dear. This year past my every thought has been of you, and I have worked and studied to make myself worthy, but always in despair, for I felt that you could not care for one like me, and that—”

away happy. I shall go patient and hopeful, believing that the doctors can and will give me back my sight, and ready to wait till I may come back to you, my own love—for I do love you, dear. This year past my every thought has been of you, and I have worked and studied to make myself worthy, but always in despair, for I felt that you could not care for one like me, and that—”

“How could you think it?” she whispered tenderly, as she nestled to him. “I never, never could have cared for him, John, nor for any one but you.”

And for those brief minutes all was the brightest of life’s sunshine in that humble room. There were tears in Mary’s sweet grey eyes, and they clung upon the lashes and lay wet upon her cheeks; but that sunshine made them flash irradiant with joy before the black cloud closed in again, and John Grange’s pale face grew convulsed with agony, as he shrank from her, only holding her hands in his with a painful clasp; while, as she gazed at him wildly, startled by the change, she saw that his eyes seemed to be staring wildly at her, so bright, unchanged, and keen that it was impossible to believe that they were blank, so plainly did they bespeak the agony and despair in the poor fellow’s breast.

“John,” she cried excitedly, “what is it? Shall I go for help? You are in terrible pain?”

“Yes, yes, dear,” he moaned; “pain so great that it is more than I can bear. No, no, don’t go, not for a minute, dear; but go then, never to come near me more. Don’t, don’t tempt me. God help me and give me strength.”

“John, dear,” he whispered piteously, as she clung to his hands, and he felt her press towards him till the throbbings of her heart beat upon his wrists.

“No, no,” he groaned. “Mary, dear, let me tell you while I have strength. I should be no man if I was silent now. I shouldn’t be worthy of you, dear, nor of the love you have shown me you could have given.”

“John, John!”

“Don’t, don’t speak to me like that,” he groaned, “or you will make me forget once more, and speak to you as I did just now. I was half mad with joy, beside myself with the sweet delight. But ’tis taking a coward’s, a cruel advantage of you in your innocence and love. Mary, Mary dear,” he said faintly; and could those eyes which stared so blankly towards her have seen, he would have gazed upon the calm, patient face, upon which slowly dawned a gentle tenderness, as she bent lower and lower as if longing to kiss his hands, which she caressed with her warm breath, while she listened to his words.

“Listen, dear,” he said, “and let me tell you the truth before you say good-bye, and go back to pray for me—for your own dear self—that we may be patient and bear it. Time will make it easier, and by and by we can look back upon all this as something that might have been.”

“Yes,” she said gently, and she raised her face a little as she knelt by the couch to gaze fondly in his eyes.

“I am going away, dear, and it is best, for what we have said must be like a dream. Mary, dear, you will not forget me, but you must think of me as a poor brother smitten with this affliction, one, dear, that I have to bear patiently to the end.”

“Yes, John,” she said, with a strange calmness in her tones.

“How could I let you tie yourself down to a poor helpless wretch who will always be dependent upon others for help? It would be a death in life for you, Mary. In my great joy I forgot it all; but my reason has come back. There is no hope, dear. I am going up to town because Mrs Mostyn wishes it. Heaven bless her for a good, true woman! But it is of no use, I know. Doctor Manning knows it well enough. My sight has gone, dear, and I must face the future like a man. You well know I am speaking the truth.”

She tried to reply, but there was a suffocating sensation at her throat, and it was some moments before she could wildly gasp out—“Yes!”

Then the strange, sweet, patient look of calm came back, with the gentle pity and resignation in her eyes as she gazed at him with sorrow.

“There,” he said, “you must go now. Bless you, Mary—bless you, dear. You have sent gladness and a spirit of hopefulness into my dark heart, and I am going away ready to bear it all manfully, for I know it will be easier to bear—by and by—when I get well and strong. Then you shall hear how patient I am, and some day in the future I shall be pleased in hearing, dear, that you are happy with some good, honest fellow who loves and deserves you; and perhaps too,” he continued, talking quickly and with a smile upon his lip, as he tried to speak cheerfully in his great desire to lessen her grief and send her away suffering less keenly—“perhaps too, some day, I may be able to come and see—”

He broke down. He could, in his weak state, bear no more, and with a piteous cry he snatched away his hands and covered his convulsed features, as he lay back there quivering in every nerve.

And then from out of the deep, black darkness, mental and bodily, which closed him in, light shone out once more, as, gently and tenderly, a slight soft arm glided round his neck, and a cold, wet cheek was laid against his hands, while in low, measured tones, every word spoken calmly, almost in a whisper, but thrilling the suffering man to the core, Mary murmured—

“I never knew till now how much a woman’s duty in life is to help and comfort those who suffer. John, dear, I have listened to everything you said, and feel it no shame now to speak out all that is in my heart. I always liked the frank, straightforward man who spoke to me as if he respected me; who never gave me a look that was not full of the reverence for me that I felt was in his breast. You never paid me a compliment, never talked to me but in words which I felt were wise and true. You made me like you, and now, once more, I tell you that when this trouble came I learned that I loved you. John, dear, this great affliction has come to you—to us both, and I know you will learn to bear it in your own patient, wise way.”

“Yes, yes,” he groaned; “but blind—blind! Mary—for pity’s sake leave me—in the dark—in the dark.”

She rose from her knees by his side, and he uttered a sob, for he felt that she was going; but she retained one of his hands between hers in a firm, cool clasp.

“No, dear,” she said softly; “those who love are one. John Grange, I will never leave you, and your life shall not be dark. Heaven helping me, it shall be my task to lighten your way. You shall see with my eyes, dear; my hand shall always be there to guide you wherever you may go; and some day in the future, when we have grown old and grey, you shall look back, dear, with your strong, patient mind, and then tell me that I have done well, and that your path in life has not been dark.”

“Mary,” he groaned, “for pity’s sake don’t tempt me; it is more than I can bear.”

“It is no temptation, John,” she said softly, and in utter ignorance that there were black shadows across her and the stricken man, she bent down and kissed his forehead. “Last Sunday only, in church, I heard these words—‘If aught but death part me and thee.’”

She sank upon her knees once more, and with her hands clasped together and resting upon his breast, her face turned heavenwards, her eyes closed and her lips moving as if in prayer, while the two shadows which had been cast on the sunlight from the door softly passed away, James Ellis and Daniel Barnett stepping back on to the green, and standing looking in each other’s eyes, till the sound of approaching wheels was heard. Then assuming that they had that moment come up, James Ellis and the new head-gardener strode once more up to the door.