Chapter 23 | A Life's Eclipse

In the dead silence which fell upon all in the bailiff’s room when Mary Ellis flung herself upon John Grange’s neck, a looker-on might have counted sixty beats of the pendulum which swung to and fro in the old oak-cased “grandfather’s clock,” before another word was uttered.

Mrs Ellis stood with her face working, as if premonitory to bursting out into a fit of sobbing; James Ellis felt something rising in his throat, and looked on with a grim kind of jealous pleasure at the lovers’ embrace; and Barnett broke the silence by making a strange grinding noise with his teeth.

“Do you—are you going to allow this?” he panted out at last.

James Ellis made a deprecating gesture with his hands, and looked uneasily at his wife, who had crossed to Grange, laid her hands upon his shoulder, and said gently—

“And we thought you were dead—we thought you were dead.”

“As I should have been, Mrs Ellis, to you all,” cried the young man proudly, “if I could not have come back to you like this.”

By this time Barnett had fully recovered the speech of which jealous rage and disappointment had nearly deprived him, and after a savage scowl at Grange, he turned upon the bailiff.

“Look here, Mr Ellis, is this your house? Are you master here?”

Ellis made an angry gesture now.

“My good sir,” he cried; “you see: what can I do?”

“Order this fellow—this beggar—this impostor out. He has no business here.”

Mary turned upon him fiercely, but her angry look faded out, and gave place to a smile of content, as she now linked her hands together about Grange’s strong right arm and looked gently in his face, as if to say, “Don’t be angry, he hardly knows what he says.”

Maddened more by this, Barnett stepped forward to separate them, but, roused now in turn, James Ellis stepped between.

“Yes,” he said firmly; “this is my house, and I am master here, Daniel Barnett. No violence, if you please.”

“As much violence as is necessary to turn this fellow out,” roared the young man. “I claim your promise, my rights. Mary, you are by your father’s words my affianced wife; keep away from that man. Mrs Ellis, stand aside, or I will not be answerable for the consequences. You coward!” he cried to Grange; “you screen yourself between two women. Now then, out with you!”

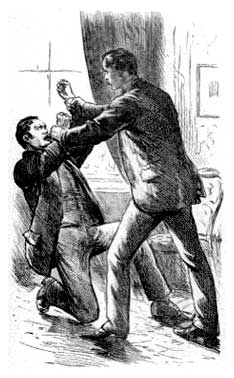

One moment John Grange had been standing there calm and happy, with the women clinging to him; the next, by a quick movement, strong yet gentle, he had shaken himself free; and as Barnett seized him by the throat to eject him from the room, he was perfectly transformed. For, with almost superhuman strength, he seized his rival in return, quickly bore him back a step or two, and then wrenched his legs from beneath him, bringing him to his knees.

“It is you who are the coward,” he cried in  a deep voice, “or you would not have forced on this before two helpless women. Mr Ellis, I claim Mary by the ties of our old and faithful love. I, John Grange, thanks to God, strong, hale, keen of sight again as once I was, a man who can and will protect her while I live. Now, sir, open that door. If there is to be a struggle between us two, it will not take place here.”

a deep voice, “or you would not have forced on this before two helpless women. Mr Ellis, I claim Mary by the ties of our old and faithful love. I, John Grange, thanks to God, strong, hale, keen of sight again as once I was, a man who can and will protect her while I live. Now, sir, open that door. If there is to be a struggle between us two, it will not take place here.”

“John!”

That one word in a tone of appeal from Mary, and he dropped his hands.

“Yes,” he said, with the calm assurance of a man who valued his strength; “you are right, dear, Daniel Barnett was half mad. That will do, sir. It is Mary’s wish that you should go, and Mr Ellis will not refuse me a hearing when his child’s happiness is at stake.”

Barnett rose slowly, looking from one to the other, and finally his eyes rested upon Ellis, who nodded gravely.

“Yes,” he said, “you’d better go, Daniel Barnett. I should not be doing my duty to my child if I fought against her now.”

He walked slowly to the door, opened it, and without another word Barnett followed him out. Five minutes later the latch of the gate was heard to click, and as all stood listening, James Ellis came in and uttered a sigh of relief. There was that in his face which made Mary, with her eyes bright and a flush upon her cheeks such as had not been seen there for a year, run to him and fling her arms about his neck, as she went into a wild fit of joyful hysterical sobbing, which it was long before she could control.

There was not much to tell, but it was to the following effect. It dated from the evening when he had been left busying himself in the garden of old Tummus’s cottage, left entirely to himself, trimming up the roses, and thinking sadly that there was no future for him in the world.

This had been going on for some time, and he was busily feeling the prickly rose strands, and taking nails and shreds from his pocket to tack the wild, blossoming shoots neatly in their places, in perfect ignorance, after a while, that he was being watched. For, though he heard hoofs upon the hard green turf beside the road, he supposed the sounds to be made by some horse returning to its stables from its pasture on the common, and did not imagine that it was mounted, as he heard it stop, and begin cropping the young shoots upon the garden hedge.

“Good-evening,” said a decisive voice suddenly, speaking as if it was a good evening, and he who spoke would like to hear any one contradict him.

“Good-evening, sir,” replied John Grange, adding the “sir,” for the voice seemed familiar, and he knew the speaker was riding.

“You remember me, eh?”

There was a slight twitching about the muscles of John Grange’s forehead as he craned his neck towards the speaker, and then he seemed to draw back, as he said sadly—

“No, sir; I seem to remember your voice, but I am blind.”

“Quite blind?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Look in my direction—hard, and now tell me: can you not make out my face, even faintly?”

“I can see that there is light, sir, where you are; but you have your back to the west. It is the warm sunset.”

“Then you are not quite blind, my lad. Well, has Mrs Mostyn forgiven you about her orchids?”

“Ah! I remember you now, sir,” cried Grange. “You are the friend—the great doctor—who came to see them.”

“To be sure I am the doctor—I don’t know about great—who stayed the night—Doctor Renton, of the Gables, Dale-by-Lyndon.”

“Yes, sir, I know. I have heard tell of your beautiful garden.”

“Indeed? Well, look here, my man. Your mistress interested me in your case, and I thought I would ride over some evening and see you. I should like you to come to me, so that I could examine your eyes, and test them a little.”

John Grange turned ghastly and fell a-trembling, as he grasped at the window-sill to steady himself.

“Come, come, that will not do,” cried the doctor quickly. “Be a man! You are weak and nervous. Try and control your feelings.”

“But—then— oh, for Heaven’s sake, speak, sir,” said Grange, in a husky whisper. “You think there is hope?”

“I do not say that, my man, but since Mrs Mostyn told me about your case, I have thought of it a great deal. Come over and see me, saying nothing to any one, for fear of disappointment. Then, if I think it is worth while, you shall come up to London and stay.”

“It is too much to bear,” groaned the sufferer.

“No: and you will bear it. But you must expect nothing. I shall in all probability fail, but if I do, you will be no worse off than you are now.”

“No, sir, I could be no worse off,” faltered Grange.

“That is the way to take it. Then you will come? But I must warn you: it may mean your being away for a year—perhaps for two.”

“I would do anything to get back my sight.”

“Then you will come? I will not communicate with Mrs Mostyn, for fear of raising false hopes. If I succeed she will forgive your sudden leaving. She is a good mistress, my lad. Pity you did not speak out the truth that day.”

John Grange flushed up.

“Indeed it was the truth, sir,” he cried angrily.

“There, there! No excitement. You will have to lead now a calm, unemotional life if I am to do you good. Good-evening. I shall expect to see you to-morrow morning, then, before I leave for town. But once more, keep your own counsel, and hope for nothing; then all that comes will be so much gain.”

He drew up the rein, touched his horse’s side, and went off at a canter, leaving Grange standing in the cottage garden, one moment with his mind illumined by hope, the next black with despair.

“No,” he cried softly; “it is too late. He can do nothing. Only that long, dark journey before me to the end. Tell no one! Lead no one to expect that I may be cured! No, not a word to any. Better away from here to be forgotten, for everything about me grows too hard to bear.”

That night he stole away in the darkness, to pause on the opposite side of the road, to whisper to the winds good-bye, and feel for a few brief minutes that he was near Mary before he said “Good-bye—for ever!” To be dead to all he knew unless he could return to them as he had been of old.

This was John Grange’s story—condensed—as he told it to the group at the cottage. Then in a low, deep tone, full of emotion—

“If I was to end my days sightless, Mary, I knew I could not come to you again; but Heaven has willed it otherwise. It has been a long, long waiting, hopeless till within the last month, and it was only within the past few days that the doctor told me that all was safe, and I might be at rest.”

“But you might have written, John, if only once,” said Mrs Ellis, with a sob in her throat.

“Yes,” he said, “I might, but I believe what I did was right, Mrs Ellis; forgive me, all of you, if I was wrong.”

What followed? Mrs Mostyn was eager to see John Grange back in his old position, but he gravely shook his head.

“No,” he said, “Mary, I am not going to trample on a man who is down. Let Dan Barnett keep the place; the doctor offers me one that will make us a happy home; and it will be, will it not?”

Mary glanced at her mother before replying, and James Ellis clasped the young man’s hand, while Mrs Ellis rushed out to have what she called a good hearty cry.

“Lor’, missus,” said old Tummus, “I never worried much about it. There’s a deal of trouble in this here life, but a lot o’ joy as well: things generally comes right in the end.”

“Not always, dear.”

“Eh? Well, never mind, this one has; and I only wish I was a bit younger, so that I could go and be under Muster John Grange.—No, I couldn’t. I can go and see ’em once in a way, but I must stop here, in this old garden, with the missus, until we die.”

“Yes, Tummus, yes,” said old Hannah. “It wouldn’t do at our time o’ life to make a change.”

“Only that last big one, old lady, to go and work in the Master’s vineyard, if He sees as we’ve done right. But there, dear, on’y to think o’ all this here trouble coming from sawing off a bit o’ ragged wood.”