Chapter 16 | A Life's Eclipse

The late Albert Smith, in his Christopher Tadpole, describes a lady whose weakness was periwinkles. Old Hannah likewise had a weakness, but it was not for that unpleasant-looking curly mollusc which has to be wriggled out with a pin, but, as she expressed it, “a big mellow Williams pear with a maddick in it.”

Old Hannah’s “maddick” was, of course, a maggot in north-country language, but it was not that she had a liking for the larva of a fly, but for the fruit in which that maggot lived for as a gardener’s wife she knew well enough that very often those were the finest pears, the first to ripen, that they fell off the tree and were useless for the purpose of dessert, and were often left to rot. So that, knowing well his wife’s weakness, old Tummus would pick up a fallen pear when he saw it under the tree in September, show it to old Dunton, who would nod his head, and the destination of that pear would be Tummus’s pocket.

Now there was a fine old pyramid pear-tree not far from the green walk, and while hoeing away at the weeds that morning, where the rich soil made them disposed to grow rampant, old Tummus came upon “the very moral” of the pear his old woman would like. It was big, mellow, and streaked with vermilion and patched with gold; and had evidently lain there two nights, for its fragrant odour had attracted a slug, which had carved a couple of round cells in the side, close to where the round black hole betrayed where the maggot lived, and sundry other marks showed that it was still at hand.

Tummus picked up that pear and laid it in the green cup formed by a young broccoli plant, went on with his hoeing till the bell rang, and was half-way to the gate, stick and lunch-basket in hand, when he remembered the pear, and hurried back—that is to say, he walked back—not quite so slowly as usual, for Tummus never ran. A man that came from “his parts” remembered that the old man had been known to run once, at some cottagers’ festival, but that was ages before, and ever since he had walked very deliberately.

Anyhow, he found the pear, and was returning to cut across the green path, when he caught sight of Daniel Barnett, and stopped short.

“I forgetted as poor old Dunton’s dead,” he thought, “He’ll turn nasty if I ask him about the pear; and what’s he a-doing of?”

Old Tummus peered through a great row of scarlet-runners and stared at his superior, and saw him bend over something on the green path, and then dart in among the bushes and disappear.

“Now what is he doing of?” old Tummus muttered. “Not a-going to— Why here comes poor Master Grange. Well, he couldn’t have seen him. Not a-setting o’ no more traps, is he?”

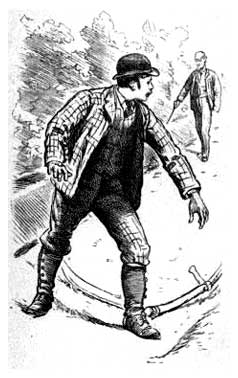

Old Tummus watched for a moment or two, and then walked right across the borders to reach the green path, breathless, just before John Grange came up, and shouted loudly—

“Ware well!”

It was just in time, for in another instant the blind man’s ankle would have struck severely against the keen scythe edge, which by accident or malignant design was so placed that its cut would have proved most dangerous, that is to say, in a slightly diagonal position—that is, it would have produced what is known to swordsmen as a draw-cut.

But the poor fellow escaped, for, at the first warning of danger he stopped short, erect in his place, with his nostrils widening and face turned towards the speaker.

“Well?” he cried. “Impossible! I am three parts of the way along the green path.”

“Aye, that’s so, Muster Grange,” said old Tummus, carefully removing the scythe, and placing it in safety by hooking the blade high up in a dense yew-tree. “No well here, but I thought it best any way to stop you.”

“To stop me? Why?” cried Grange.

“’Cause some one as ought to be kicked out o’ the place left his scythe lying across the grass ready for you to chop your shins. It’s all right now.”

They walked on in silence till they reached a gate opening upon the green meadow, where John Grange stopped short with his hand resting upon the upper bar.

“What is it, my lad?” said old Tummus.

“I was only thinking of how helpless I am. I thank you, Tummus,” he said simply, as he turned and held out his hand. “I might have cut myself terribly.”

“Aye, you might, my lad. There, go on to your dinner, and tell the missus I shall be there directly.”

John Grange wrung the old man’s hand, and went on in perfect ignorance of the trap that had been laid, with the idea that if he were injured and had to go to a hospital once again, it was not likely that he would return to the gardens; while old Tummus went off to the tool-shed, a quiet, retired nook, suitable for a good think, to cogitate as to what he should do under the circumstances.

His first thought was to go straight to Mrs Mostyn, and tell her what he had seen, and also about the orchids, but he argued directly that his mistress would not believe him.

“For I didn’t see him upset the orchards, and as to this here business,” he thought, “nobody wouldn’t believe as a human being would go and do such a thing. Dunno as I would mysen if I hadn’t seen it, and I arn’t quite sure now as he meant to do it, though it looks as much like it as ever it could. He’s got his knife into poor John Grange, somehow, and I don’t see why, for the poor fellow arn’t likely to do much harm to anybody now.”

Then he considered for a bit as to whether he should tell John Grange what he had seen; but he concluded that he would not, for it would only make the poor fellow miserable if he believed him.

Old Tummus was still considering as to the best course when the two o’clock bell rang, and he jumped up to go back to his work.

“Never mind,” he thought, with a grin, “I dessay there’ll be a few cold taters left, and I must have them with my tea.”

That same evening, after old Tummus had finished a meal which more than made up for his abstemiously plain dinner, he made up his mind to tell John Grange out in the garden.

“For,” said he to himself, “I mayn’t be there next time there’s a scythe across the path, and who knows but what some day it may be the well in real airnest; Dan Barnett may leave the lid off, or uncover the soft-water tank, and the poor chap be drowned ’fore he knows it.”

But when he went out he found his lodger looking so happy and contented, tying up the loose shoots of the monthly rose which ran over the cottage, that he held his tongue.

“It arn’t my business,” he argued, and he went off to meet an old crony or two in the village.

“Don’t let any one run away with the house while I’m gone, Mr John,” said old Hannah, a few minutes later. “I’m going down to the shop, and I shan’t be very long.”

Grange nodded pleasantly, and went on with his work.

That night Mary Ellis sat at her open window, sad and thoughtful, inhaling the cool, soft breeze which came through the trees, laden with woodland scents. The south-eastern sky was faintly aglow, lit up by the heralds of the rising moon, and save the barking of a dog up at the kennels, all was still.

She was thinking very deeply of her position, and of Daniel Barnett’s manner towards her the last time they met. It was plain enough that her father favoured the head-gardener’s visits, and in her misery her thoughts turned to John Grange, the tears falling softly the while. All at once she started away from the window, for, plainly heard, a low, deep sigh came from the dark shadow of the trees across the road.

Daniel Barnett? John Grange? There so late? Who could it be?

Her heart said John Grange, for the wish was father to the thought.

But she heard nothing more for a few minutes, and then in a whisper, hardly above the breath, the words—

“Good-bye—for ever, perhaps—good-bye!”

Then came the hurrying sound of steps on the dewy grass at the side of the road, and the speaker was gone, leaving Mary leaning out of the window, excited and trembling violently, while her heart beat in the stillness of the night as if it were the echo of the hurried pace rapidly dying away.

“It could not be—it could not be,” she sighed at last, as she left the window to prepare for bed. “And yet he loves me so dearly. But why should he say that?”

She stopped in the middle of the room, and the words seemed to repeat themselves—

“Good-bye—for ever, perhaps—good-bye!”

The tears fell fast as she felt that it was so like John Grange in his manly, honourable way of treating their positions.

“He feels it all so terribly that it would be like tying me down—that it would be terrible for me—because he is blind.”

She wiped her eyes, and a bright smile played about her lips, for there, self-pictured, was a happy future for them both, and she saw herself lightening the great trouble of John Grange’s life, and smoothing his onward course. There was their happy home with her husband seeing with her eyes, guided always by her hand, and looking proud, manly, and strong once more as she had known him of old.

“It will only draw us closer together,” she said softly; “and father will never refuse when he once feels it’s for my happiness and for poor John’s good.”

But the smile died out as black clouds once more rose to blot out the pleasant picture she had formed in her mind; and as the mists gathered the tears fell once more, hot, briny tears which seemed to scald her eyes as she sank upon her knees by the bedside and buried her face in her hands.

That night Mary Ellis’s couch remained unpressed, and the rising sun shone in at the window upon her glossy hair where she crouched down beside her bed.

It was a movement in the adjoining room which roused her from the heavy stupor into which she had fallen, for it could hardly be called a natural sleep, and she started up to look round as if feeling guilty of some lapse of duty.

For a few minutes she suffered from a strange feeling of confusion accompanied by depression. Then by degrees the incidents of the past night came clearly to her mind, and she recalled how she had sunk down by her bed to pray for help and patience, and that the terrible affliction might be lightened for him she loved, and then all had become blank.

A few minutes before Mary’s face had looked wan and pale, now it was suffused by a warm glow that was not that of the ruddy early morning sun. For the hope had risen strongly in her breast that, in spite of all, the terrible affliction would be lightened, and by her.