Chapter 6 | Pen's Patient | !Tention

Punch’s appealing sign was sufficient to chase away the imaginative notions that had beset Pen’s awakening. His hand went at once to the water-bottle slung to his side, and, as he held the mouth to his comrade’s lips and forgot the pain he suffered in his strained and stiffening joints, he watched with a feeling of pleasure the avidity with which the boy drank; and as he saw the strange bird flit by once more he recalled having heard of such a bird living in the west country.

“Yes,” he said to himself, “I remember now—the dipper. Busy after water-beetles and perhaps after tiny fish.—You are better, Punch, or you wouldn’t drink like that;” and he carefully lowered the boy’s head as he ceased drinking. “Yes, and though I can’t hear you, you have come to your senses again, or you would not look at me like that.—Ah, I forgot all about them!” For a sound other than that produced by the falling waters came faintly to his ear. It was from somewhere far above, and echoed twice. “Yes, I had forgotten all about them.”

He began looking anxiously about him, taking in the while that he was close to the river where it ran in a deep, precipitous gully; and as he looked up now to right and then to left, eagerly and searchingly, for the danger that he knew could not be far away, his eyes ranged through densely wooded slopes, lit up here and there by the morning sunshine, and always sweeping the sides of the valley in search of the vedettes, but without avail, not even the rugged mule-path that ran along the side being visible.

“They are not likely to see us here,” Pen said to himself, “and they can’t have seen me coming down. Oh, what a job it was! I feel as if I must have been walking in my sleep half the time, and I am so stiff I can hardly move. But I did it, and we must be safe if we can keep out of sight; and that ought to be easy, for they are not likely to come down here. Now, what’s to be done?”

That was a hard question to answer; but growing once more full of energy now that he was satisfied that there was no immediate danger, Pen stepped back lamely, as if every muscle were strained, to his companion’s side, to be greeted with a smile and a movement of the boy’s lips.

“Now, let’s see to your wound,” he said, with his lips to the boy’s ear; and he passed one hand under Punch’s wounded shoulder to try and turn him over. This time, as Punch’s lips parted and his face grew convulsed with pain, Pen’s ears mastered the roar, and he heard the sufferer’s cry.

“Hurt you too much?” he said, as he once more put his lips to the boy’s ear.

The answer was a nod.

“Well,” thought Pen, “he must be better, so I’ll let him be; but we can’t stop here. I must try and get him through the trees and away from this horrible noise. But I can’t do it now. At least, I don’t think I can. Then, what’s next?”

The inaudible reply to the question came from somewhere inside, and he bent closer over Punch once more.

“Aren’t you hungry?” he roared in his ear.

The boy shook his head.

“Well, I am,” shouted Pen.—“Oh, how stupid! This is like telling the enemy where we are, if they are anywhere within hearing. Hullo, what does this mean?” For he suddenly caught sight of the goat springing from stone to stone low down the stream as if coming to their side of the rushing water; and with the thought filling his mind that a tame goat like this must have an owner who was more likely to be an enemy of strangers than a friend, Pen began searching the rugged slopes on both sides of the river, but in vain. The goat, which had crossed, was now coming slowly towards them, appearing to be quite alone, though soon proving itself to be quite accustomed to the presence of human beings, for it ended by trotting over the sand and shingle at the river’s edge till it had approached them quite closely, to stand bleating at them, doubtless imploringly, though no sound was heard.

This lasted for a few minutes, and then the goat moved away, passing Punch, and disappearing upward through the dense growth, and apparently making its way up by the side of the great fall.

No sooner was it out of sight than a thought struck Pen; and, making a sign to his companion that meant “I won’t be long,” he shouldered his rifle and began to climb upwards in the direction taken by the goat.

He was beginning to regret now that he had not started sooner, for there was no sign of the little beast, and he was about to turn when, just to his right, he noted faint signs of what seemed to be a slightly used track which was easy to follow, and, stepping out, he observed the trees were more open, and at the end of a few minutes he found himself level with the top of the falls, where the river was gliding along in a deep, glassy sheet before making its plunge over the smooth, worn rocks into a basin below.

He had just grasped this when he saw that the faint track bore off to the right, and caught sight of the goat again moving amongst the trees, and for the next few minutes he had no difficulty in keeping it in sight, and, in addition, finding that it was making for what seemed to be the edge of another stream which issued from a patch of woodland on its way to the main torrent.

“I must get him here if I can,” thought Pen, for the roar of the falling waters was subdued into a gentle murmur, and to his surprise he caught sight of a shed-like building amongst the trees, fenced in by piled-up pieces of stone evidently taken from the smaller stream which he approached; and it was plain that this was the spot for which the goat had been making.

The young rifleman stopped short, trying to make out whether the place was inhabited; but he could see no sign save that the goat was making for the stone fence, on to which the active beast leaped, balanced itself carefully for a few moments, and then sprang down on the other side, to be greeted by a burst of bleating that came from apparently two of its kind within.

Pen stood screened by the trees for a time, fully expecting to see some occupant of the hut make his appearance; but the bleating ceased directly, and, approaching carefully, the young private stood at last by the rough stone wall, looking down on a scene which fully explained the reason for the goat’s visit.

She had returned to her kids; and after climbing the wall a very little search showed the visitor that the goat and her young ones were the sole occupants of the deserted place.

It was the rough home of a peasant who had apparently forsaken it upon the approach of the French soldiery. Everything was of the simplest kind; but situated as Pen Gray was it presented itself in a palatial guise, for there was everything that he could wish for at a time like that.

As before said, it was a shed-like structure; but there was bed and fireplace, a pile of wood outside the door, and, above all, a roof to cover those who sought shelter.

“Yes, I must bring him here somehow,” thought Pen as he caught sight of a cleanly scrubbed pail and a tin or two hanging upon nails in the wall. But he saw far more than this, for his senses were sharpened by hunger; and with a smile of satisfaction he hurried out, noting as he passed them that the kids, keen of appetite, were satisfying their desire for food; and, hurrying onwards, he made his way back to where he had left his companion lying in the dry, sandy patch of shingle; and some hours of that forenoon were taken up in the painful task of bearing the wounded lad by slow degrees to where, after much painful effort, they could both look down upon the nearly hidden shed.

“How are you now, Punch?” asked Pen, turning his head upwards.

There was no reply.

“Why, Punch,” cried Pen, “you are not asleep, are you?”

“Asleep!” said the boy bitterly; and then, in a faint whisper, “set me down.”

Pen took a step forward to where he could take hold of a stunted oak-bough whose bark felt soft and strange; and, holding tightly with one hand, he held his burden with the other while he sank slowly, the branch bending the while till he was kneeling. Then he slid his load down amongst the undergrowth and quickly opened his water-bottle and held it to the boy’s lips.

“Feel faint, lad?” he said.

Again there was no answer; but Punch swallowed a few mouthfuls.

“Ah, that’s better,” he said. “Head’s swimming.”

“Well, you shall lie still for a few minutes till you think you can bear it, and then I want you to get down to that hut.”

Punch looked up at him with misty eyes, wonderingly.

“Hut!” he said faintly. “What hut?”

“The one I told you about. You will be able to see it when you are better. There’s a rough bed there where you will be able to lie and rest till your wound heals.”

“Hut!”

“Oh, never mind now. Will you have some more water?”

The boy shook his head.

“Not going to die, am I?” he said feebly.

“Die! No!” cried Pen, with his heart sinking. “A chap like you isn’t going to die over a bit of a wound.”

“Don’t,” said the boy faintly, but with a tone of protest in his words. “Don’t gammon a fellow! I am not going to mind if I am. Our chaps don’t make a fuss about it when their time comes.”

“No,” said Pen sharply; “but your time hasn’t come yet.”

The boy looked up at him with a peculiar smile.

“Saying that to comfort a fellow,” he almost whispered; “only, I say, comrade, you did stick to me, and you won’t—won’t—”

“Won’t what?” said Pen sharply. “Leave you now? Is it likely?”

“Not a bit yet,” said the poor fellow faintly; “but I didn’t mean that.”

“Then what did you mean?” cried Pen wonderingly.

The poor lad made a snatch at his companion’s arm, and tried to draw him down.

“What is it?” said Pen anxiously now, for he was startled by the look in the boy’s eyes.

“Want to whisper,” came in a broken voice.

“No; you can’t have anything to whisper now,” said Pen. “There, let me give you a little more water.”

The boy shook his head.

“Want to whisper,” he murmured in a harsh, low voice.

“Well, what is it? But you had better not. Shut your eyes and have a bit of a nap till you are rested and the faintness has gone. I shall be rested, too, then, and I can get you down into the hut, where I tell you there’s a bed, and, better still, Punch, a draught of sweet warm milk.”

“Gammon!” said the boy again; and he hung more heavily upon Pen’s arm.—“Want to whisper.”

“Well, what is it?” said Pen, trying hard to master the feeling of despair that was creeping over him.

“Them wolves!” whispered the boy. “Don’t let them get me, comrade, when I’m gone.”

“You shut your eyes and go to sleep,” cried Pen angrily.

“No,” said the boy, speaking more strongly now. “I aren’t a baby, and I know what I’m saying. You tell me you won’t let them have me, and then I will go to sleep; and then if I don’t wake up no more—”

“What!” cried Pen, speaking with a simulated anger, “you won’t be such a coward as to go and leave me all alone here?”

The boy started; his eyes brightened a little, and he gazed half-wonderingly in his companion’s face.

“I—I didn’t think of that, comrade,” he faltered. “I was thinking I was going like some of our poor chaps; but I don’t want to shirk. There, I’ll try not.”

“Of course you will,” said Pen harshly. “Now then, try and have a nap.”

The boy closed his eyes, and in less than a minute he was breathing steadily and well, but evidently suffering now and then in his sleep, for the hand that clasped Pen’s gave a sudden jerk at intervals.

Quite an hour, during which the watcher did not stir, till there was a sharper twitch and the boy’s eyes opened, to look wonderingly in his companion’s as if he could not recall where he was.

“Have a little water now, Punch?”

“Drop,” he said; but the drop proved to be a thirsty draught, and he spoke quite in his senses now as he put a brief question.

“Is it far?” he said.

“To the hut? No. Do you think you can bear me to get you on my back again?”

“Yes. Going to. Look sharp!”

But as soon as the boy felt his companion take hold of his hand after restopping the water-bottle, Punch whispered, “Stop!”

“What is it? Would you like to wait a little longer?”

“No. Give me a bullet out of a cartridge.”

“A bullet? What for?”

“To bite,” said the boy with a grim smile.

Pen hesitated for a moment in doubt, looking in the boy’s smiling eyes the while. Then, as a flash of recollection of stories he had heard passed through his mind, he hastily drew a cartridge from his box, broke the little roll open, scattering the powder and setting the bullet free before passing it to his companion, who nodded in silence as he seized the piece of lead between his teeth. Then, nodding again, he raised one hand, which Pen took, and seizing one of the branches of the gnarled tree he bent it down till he got it close to his companion, and bade him hold on with all his might.

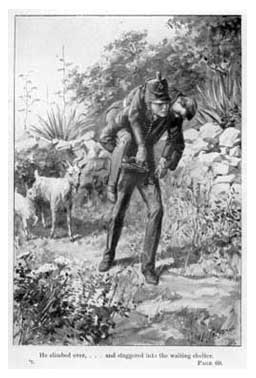

Punch’s fingers closed tightly upon the bough, which acted like a spring and helped to raise its holder sufficiently high for Pen to get him once more upon his shoulders, which he had freed from straps thrown down beside his rifle.

“Try and bear it,” he panted, as he heard the low, hissing breath from the poor fellow’s lips, and felt him quiver and wince. “I know it’s bad,” he added encouragingly, “but it won’t take me long.”

It did not, for in a very few minutes he had reached the rough stone wall, to which he shifted his burden, stood for a few moments panting, and then climbed over, took the sufferer in his arms, and staggered into the waiting shelter, where the next minute Punch was lying insensible upon the bed.

“Ha!” ejaculated Pen as he passed the back of his hand across his streaming forehead.

This suggested another action, but it was the palm of his hand that he laid across his companion’s brow.

“All wet!” he muttered. “He can’t be very feverish for the perspiration to come like that.”

Then he started violently, for a shadow crossed the open door, and he involuntarily threw up one hand to draw his slung rifle from his shoulder, and then his teeth snapped together.

There was no rifle there. It was lying with his cartouche-box right away by the stunted oak, as he mentally called the cork-tree.

The next minute he was breathing freely, for the deep-toned bleat of the goat arose, and he looked out, to see that it was answerable for the shadow.

“Ah, you will have to pay for this,” he muttered, as he started to run to where his weapon lay, his mind full now of thoughts that in his efforts over his comrade had been absent.

He was full of expectation that one or other of the vedettes might have caught sight of him bearing his load to the hut; and, with the full determination to get his rifle and hurry back to defend himself and his companion for as long as the cartridges held out, he started with a run up the slope, which proved to be only the stagger of one who was utterly exhausted, and degenerated almost into a crawl.

He was back at last, to find that Punch had not moved, but seemed to be sleeping heavily as he lay upon his sound shoulder; and, satisfied by this, Pen laid his rifle and belts across the foot of the bed and drew a deep breath.

“I can’t help it,” he nearly groaned. “It isn’t selfish; but if I don’t have something I can do no more.”

Then, strangely enough, he uttered a mocking laugh as he stepped to a rough shelf and took a little pail-like vessel with one stave prolonged into a handle from the place where it had been left clean by the last occupant of the hut, and as he stepped with it to the open door something within it rattled.

He looked down at it in surprise and wonder, and it was some moments before he grasped the fact that the piece of what resembled blackened clay was hard, dry cake.

“Ah!” he half-shouted as he raised it to his lips and tried to bite off a piece, but only to break off what felt like wood, which refused to crumble but gradually began to soften.

Then, smiling grimly, he thrust the cake within his jacket and stepped out, forgetting his pain and stiffness, to find to his dismay that there was no sign of the goat.

“How stupid!” he muttered the next minute. “My head won’t go. I can’t think.” And, recalling the goat’s former visit to the rough shelter, he hurried to where he had been a witness of its object, and to his great delight found the animal standing with half-closed eyes nibbling at some of the plentiful herbage while one of its kids was partaking of its evening meal.

Pen advanced cautiously with the little wooden vessel, ready to seize the animal by one of its horns if it attempted to escape, as it turned sharply and stared at him in wonder; but it only sniffed as if in recognition at the little pail, and resumed its browsing. But the kid was disposed to resent the interruption of the stranger, and some little force had to be used to thrust it away, returning again and again to begin to make some pretence of butting at the intruder.

Pen laughed aloud at the absurdity of his task as he finally got rid of the little animal, and made his first essay at milking, finding to his great delight that he was successful, while the goat-mother took it all as a matter of course, and did not move while her new friend refreshed himself with a hearty draught of the contents of the little pail; and then, snatching at a happy thought, drew the hardened cake from his breast and placed it so that it could soak up the soft warm milk which flowed into the vessel.

“Ah!” sighed the young soldier, “who’d have thought that taking the king’s shilling would bring a fellow to this? Now for poor Punch. Well, we sha’n’t starve to-night.”

Once more as he turned from the goat the thought assailed him that one of the vedettes might be in sight; but all was still and beautiful as he stepped back slowly, eating with avidity portions of the gradually softening black-bread, and feeling the while that life and hope and strength were gradually coming back.

“Now for poor Punch!” he muttered again; and, entering the rough shelter once more, he stood looking down upon the wounded boy, who was sleeping heavily, so soundly that Pen felt that it would be a cruelty to rouse him. So, partaking sparingly of his novel meal, he placed a part upon a stool within reach of the rough pallet.

“Wounded men don’t want food,” he muttered. “It’s Nature’s way of keeping off fever; and I must keep watch again, and give him a little milk when he wakes. Yes, when he wakes—when he wakes,” he muttered, as he settled himself upon the earthen floor within touch of his sleeping comrade. “Mustn’t close the door,” he continued, with a little laugh, “for there doesn’t seem to be one; and, besides, it would make the place dark. Why, there’s a star peeping out over the shoulder of the mountain, and that soft, low, deep hum is the falling water. Why, that must be the star I used to see at home in the old days; and, oh, how beautiful and restful everything seems! But I mustn’t go to sleep.—Are you asleep, Punch?” he whispered softly. “Poor fellow! That’s right. Sleep and Nature will help you with your wound; but I must keep awake. It would never do for you to rouse up and find me fast. No,” he half-sighed. “Poor lad, you mustn’t go yet where so many other poor fellows have gone. A boy like you! Well! It’s the—fortune—fortune—of war—and—and—”

Nature would take no denial. Pen Gray drew one long, deep, restful breath as if wide-awake, and then slowly and as if grudgingly respired.

Fast asleep.