Chapter 37 | After Wiggling | !Tention

“Where do you suppose we are, Punch?”

“Don’t quite know,” was the reply. “Chap can’t think with his arms strapped behind him and his wrists aching sometimes as if they were sawn off and at other times being all pins and needles. Can you think?”

“Not very clearly; and it has been too dark to see much. But where should you say we are? Quite in a new part of the country?”

“No; I think we came nearly over the same ground as we were going after we left that good old chap’s cottage; and if we waited till it was quite daylight, and we could start off, I think I could find my way back to where we left the old man.”

“So do I,” said Pen eagerly. “That must be the mountain that the contrabandista captain took us up in the darkness.”

“Why, that’s what I was thinking,” said Punch; “and if we had gone on a little farther I think we should have got to the place where the Frenchies attacked us. Of course I ain’t sure, because it was all in the darkness. But, I say, Mr Contrabando and his fellows have given up the pursuit. I haven’t heard anything of them for hours now.”

“No,” said Pen; “we may be sure that they have given it up, else we shouldn’t be halted here. I fancy, Punch—but, like you, I can’t be sure—that the Frenchmen have been making for the place where they surprised us after being driven down the mountain pass.”

“That’s it,” said Punch; “and our friends, after beating off the enemy, have gone back to their what-you-may-call-it quarters—mine, didn’t they call it?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then, that’s what we have got to do—get away from here and go back and join Mr Contrabando again.”

“Impossible, Punch, even if we were free.”

“Not it! Why, I could do it in the dark if I could only get rid of these straps, now that the Frenchies are beaten.”

“Not beaten, Punch; only driven back, and I feel pretty sure in thinking it out that they have come to a halt here in what I dare say is a good, strong place where they can defend themselves and wait for reinforcements before attacking again.”

“Oh, they won’t do that,” said Punch roughly. “They had such a sickener last night.”

“Well, I can’t be sure,” said Pen; “but as far as I can make out they have a lot of wounded men lying about here in this bit of a valley, and there are hundreds of them camped down about the fires. They wouldn’t have lit those fires if it hadn’t been a strong place.”

“I suppose not,” said Punch. “I never thought of that. Because they would have been afraid to show the smugglers where they were, and it sounded when they were talking as if there were hundreds and hundreds of them—regiments, I think. One couldn’t see in the night, but while I was lying awake I thought there were thousands of them.”

“Say hundreds, Punch. Well, I haven’t spoken to you much lately, for I thought you were asleep.”

“Asleep! Not me! That’s what I thought about you; and I hoped you was, so that you could forget what a muddle we got into. Well, I don’t know how you feel now, but what I want to do is to get away from here.”

“Don’t talk so loud,” said Pen; “there are those fellows on sentry, and they keep on coming very near now and then.”

“That don’t matter,” said Punch, “they can’t understand what we talk about. What do you say to having a go at getting our arms loose?”

“They would find it out, and only bind us up again.”

“Yes, if we stopped to let ’em see.”

“Then you think we could get away, Punch?”

“To be sure I do; only we should have to crawl. And the sooner the better, for once it gets light the sentries will have a shot at us, and we have had enough of that. I say, though, didn’t they pick us up because they thought we were wounded?”

“The men did; and then one of the officers saw our uniforms and that we were the two who had been taken prisoners when they made their rush.”

“Oh, that was it, was it?” said Punch. “Well, what do you say? Hadn’t we better make a start?”

“How?” said Pen. “I have been trying again and again to get my arms loose, and I am growing more helpless than ever.”

Punch gave a low grunt, raised his head a little, and tried to look round and pierce the darkness, seeing very little though but the fact that they were surrounded by wounded men, for the most part asleep, though here and there was one who kept trying to move himself into an easier position, but only to utter a low moan and relapse into a state of semi-insensibility.

About a dozen paces away, though, he could just make out one of the sentries leaning upon his musket and with his back to them. Satisfied with his scrutiny, Punch shifted his position a little, drawing himself into a position where he could get his lips close to his companion’s ear.

“Look here,” he said, “can you bite?”

“Bite! Nonsense! Who could think of eating now?”

“Tchah!” whispered Punch, “who wants to eat? I have been wiggling myself about quietly ever since they set me down, and I have got my hands a bit loose. Now, I am just going to squirm myself a bit farther and turn over when I have got my hands about opposite your mouth, and I want you to set-to with your teeth and try hard to draw the tongue of the strap out of the buckle, for it’s so loose now that I think you could do it.”

“Ah! I’ll try, Punch,” whispered Pen.

“Then if you try,” said the boy, “you’ll do it. I know what you are.”

“Don’t talk, then,” replied Pen excitedly, “but turn over at once. Why didn’t you think of this before? We might have tried at once, and had a better chance, for it will be light before long.”

“Didn’t think of it. My arms hurt so that they made me stupid.”

Giving himself a wrench, the boy managed to move forward a little, turned over, and then worked himself so that he placed his bandaged wrists close to his comrade’s mouth, and then lay perfectly still, for the sentry turned suddenly as if he had heard the movement.

Apparently satisfied, though, that all was well, he changed his position again, and then, to the great satisfaction of the two prisoners, he shouldered his musket and began to pace up and down, coming and going, and halting at last at the far end of his beat.

Then, full of doubt but eager to make an effort, Pen set to work, felt for the buckle, and after several tries got hold of the strap in his teeth, tugging at it fiercely and with his heart sinking more and more at every effort, for he seemed to make no progress.

Twice over, after tremendous efforts that he half-fancied loosened his teeth, he gave up what seemed to be an impossibility; but he was roused upon each occasion by an impatient movement on the part of Punch.

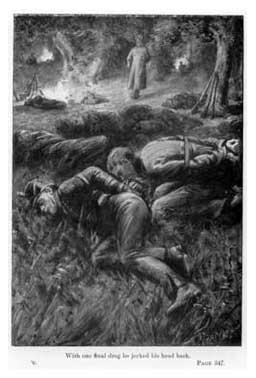

“It’s of no use,” he thought. “I am only punishing myself more and more;” and, fixing his teeth firmly once more in the leather, he gave one shake and tug such as a wild beast might have done in worrying an enemy. With one final drag he jerked his head back and lay still with his jaws throbbing and the sensation upon him that he had injured himself so that several of his teeth had given way.

“It’s no good. It’s of no use, Punch,” he said to himself; for the boy shook his wrists sharply as if to urge him to begin again. “I can’t do it, and I won’t try;” when to his astonishment he felt that his comrade was moving and had forced himself back with a low, dull, rustling sound so that he could place his lips to his ear again; and to Pen’s surprise the boy whispered, “That last did it, and I got the strap quite loose. My! How my wrists do ache! Just wait a bit, and then I will pull you over on to your face and have a turn at yours.”

Pen felt too much confused to believe that his companion had succeeded, but he lay perfectly still, with his teeth still aching violently, till all at once he felt Punch’s hands busy about him, and he was jerked over upon his face.

Then he felt that the boy had raised himself up a little as if to take an observation of their surroundings before busying himself with the straps that bound his numbed wrists.

“Lie still,” was whispered, “don’t flinch; but I have got my knife out, and I am going to shove it under the strap. Don’t holloa if it hurts.”

Pen set his aching teeth hard, and the next minute he felt the point of the long Spanish clasp-knife which his comrade carried being thrust beneath one of the straps.

“He will cut me,” thought Pen, for he knew that the pressure of the strap had made his flesh swell so that the leather was half-bedded in his arm; but setting his teeth harder—the pain he felt there was more intense—while, when the knife-blade was being forced under the strap he only suffered a dull sensation, and then grew conscious that as the knife was being thrust beneath the strap it steadily divided the bond, so that directly after there was a dull sound and the blade had forced its way so thoroughly that the severed portions fell apart; sensation was so much dulled in the numbed limbs that he was hardly conscious of what had been done, but he knew that one extremely tight ligature had ceased its duty, though he could hardly grasp the idea that one of his bonds was cut.

Then a peculiar throbbing sensation came on, so painful that it diverted the lad’s attention from the continuation of Punch’s task, and before he could thoroughly grasp it Pen found that the sharp blade had been thrust under another strap, dividing it so that the leather fell apart, and he was free.

But upon his making an effort to put this to the proof it seemed as if his arms were like two senseless pieces of wood; but only for a few minutes, till they began to prove themselves limbs which were bearers of the most intense agony.

Click! went Punch’s closing knife-blade; and then he whispered, “That’s done it! Now, when you are ready, lead off right between those sleeping chaps. Creep, you know, in case the sentry looks round.”

“A minute first,” whispered Pen; “my arms are like lead.”

“So’s mine. I say, don’t they ache?”

Pen made no reply, but lay breathing hard for a time; and then, raising his head a little so as to make sure of the safest direction to take, he turned towards his comrade and whispered, “Now then: off!”