Chapter 1 | How Spring Was Coming | Featherland

“Hallo, old Yellowbill! what’s brought you out so early?” said a fine fat thrush, one bright spring morning, stopping for a moment to look at his companion, and leaving the great broken-shelled snail he had rooted out of the ivy bush curling about upon the gravel path. “Hallo, old Yellowbill! what’s brought you out so early?”

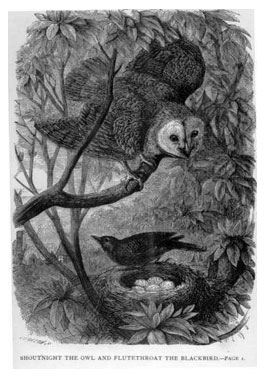

“What’s that to you, old snail-crusher?” said the blackbird, for he was in rather an ill temper that morning, through having had a fright in the night, and being woke up by old Shoutnight the owl, who had been out mousing and lost his wife, and sat at last in the ivy-tod halloaing and hoo-hooing, till the gardener’s wife threw her husband’s old boot out of the window at him, when he went flop into the laurel bush, and banged and bounced about, hissing and snapping with his great bill, while his goggle eyes glowed so angrily that the blackbird’s good lady popped off her nest in a hurry and broke one of her eggs, and, what was worse, was afraid to go back again till the eggs were nearly cold; and then she was so cross about it, that although the broken egg was only a bad one, she turned round upon Flutethroat, her husband, who had been almost frightened to death, and told him in a pet it was all his fault for not picking out a better place for the nest.

So it was no wonder that Flutethroat, the blackbird, turned grumpy when neighbour Spottleover, the thrush, called him “Yellowbill;” for of course he did not like it any better than a man with a red nose would like to be called Hot-poker. But it was such a fine morning, and there were so many dew-worms lying out in the cool grass that the neighbours could not stop to be crabby. So Spottleover flew off with his snail, and Flutethroat soon had hold of a thumping, great worm, and set to work, tug-tug, to draw it from its hole, and then pulled and poked it about till it was easily to be packed in a knot, when he took it in his bill and flew off to the laurel bush, where Mrs Flutethroat was busy sitting upon four green speckly eggs, and waiting very impatiently for her breakfast.

Just then the sun cocked one side of his great round face over the hill, and looked down upon Greenlawn garden, where all this took place, and tried to make the dew-drops glitter and shine upon the grass and leaves; but he could not, for Dampall, the mist, was out, and had spread himself all over the place like a great wet smoke; and for ever so long he would not move, for he did not like the sun at all, because he, as a mist, was good friends with the moon, and used to let her beams dance all over him. But it was a fine spring morning, and the sun had got up in a good humour, and had no end of business to get through that day. There was all the water on the lowlands to drink up; all the little green buds just coming out on the trees to warm; the bees to waken up and send honey-seeking amongst the crocuses, primroses, and violets, that were all peeping out from amongst last autumn’s dead leaves; flies to hunt out of crevices where they had been asleep all the winter; and old Bluejacket, the watchman beetle, to wake up from his long doze; as well as Nibblenut the squirrel, Spikey the hedgehog, and ever so many more old friends and neighbours; and so, of course, he was not going to be put down by a cold, raw mist. And, “Pooh!” he said, looking sideways at it, and, as he got his face a little higher, right through it, “Pooh! that won’t do; you’ve been up all night, so be off to bed, and don’t think that I am going to put up with any of your nonsense. You had it all your own way whilst I was busy down south; but I’ve come back now to set things right; so off you go.”

Whereupon the mist looked as raw and cross as he could, but it was of no use; so he rolled himself off the lawn, down the hollow, and into the vale, where he hung about over the river ever so long, evidently meaning to come back again; but the sun was after him in a twinkling, and so there was nothing else for it, and the poor mist crept into a cave by the river’s bank, and went to sleep all day.

“Hooray!” said the birds when the mist was gone; and all the little pearly dew-drops were sparkling and twinkling on the grass. The daisy opened his eye and sat watching the grass grow; while the bees—as their grand friends, the great flowers, had not yet come to town—came buzzing about, and carried the news from daisy to daisy that Queen Spring was coming, and that there were to be grander doings than ever in the garden. “Hooray!” said the birds, for they knew it too, and they all set to work, singing in the gladness of their hearts to think that old Niptoes the winter had gone at last, and that there would be plenty to eat, and no more going about with feathers sticking up, and no leaves to shelter anybody by night.

A fine place was Greenlawn, for there the birds had it all their own way; not a nest was touched; not a gun was ever seen; and as to powder, the rooks up in the lime-trees never smelt it in their lives; but built their great awkward nests, and punched the lawn about till the grubs used to hold consultations together, and at last determined to emigrate, but as no one would come out of the ground to make a start, any more than a mouse could be found bold enough to put the bell on the cat’s neck as told in the old fable, the grubs stopped there year after year, and had a very, very hard time of it. It was a regular feast-land for the birds; there were no such buds anywhere else to peck at, for so the tomtits and bullfinches thought; no such strawberries for the blackbirds and thrushes; and as to the elder-berries down by the pond, the starlings used to come in flocks to strip them off, and then carelessly leave ever so many wasting upon the ground.

“Hooray!” said the birds that morning; and they sang and sang so loudly and sweetly that the master of the garden opened his window and sat down to listen to them. But they had something else to do besides sing; there was courting, and wedding, and building, and housekeeping, going on all over the garden. Mr and Mrs Redbreast were just married, and shocking as it may seem, were quarrelling about the place where they should live. Mr Robin wanted the snug quarters in the ivy, down by the melon pits; while Mrs Redbreast said it was draughty, and made up her mind to live in the rockery amongst the fern. Mr and Mrs Specklems, the starlings, were very undecided about the hole in the chimney-stack, so much so, that when they had half-furnished it, they altered their minds and went to the great crack half way up the old cedar, and settled there; “like a pair of giddy unsettled things,” as the jackdaw said, who meant to have been their neighbour; but was not above taking possession of the soft bed they had left behind. As to Spottleover, he, too, was out of temper all the rest of the day, and when Flutethroat met him in the afternoon he found his neighbour all smeared with clay, and looking for all the world like a clay-dabbing plasterer as he was.

“There, just look at those wretched little cocktail things,” said Flutethroat, pointing to the wrens, hard at work at their nest, just when the cock bird flew up on to the wall, perked about for a moment, sang his song in a tremendous hurry, and seemed to leave off in the middle, as he popped down again to his work.

“Good job, too,” said the thrush; “I wish mine was a cocktail, and then I shouldn’t have had these nobs of clay sticking to it;” saying which he showed his neighbour three or four little clay-pellets attached to his tail-feathers, evidently caught up when fetching his mortar from the pond side.

“Ah! it’s a stupid plan that plastering,” said a conceited-looking chaffinch, joining in the conversation. “I wonder your children don’t die of rheumatic gout.”

“Take that for your impudence, you self-satisfied little moss-weaver;” saying which the thrush gave the new-comer such a dig in the back with his hard bill, that the finch flew off in a hurry, vowing that he would pass no more opinions upon other people’s building.