Chapter 24 | A Surprise | Blue Jackets

I don’t think the Chinese authorities were very grateful to us of the Teaser,—there, you see, I say us, for I did do something to help in routing out and destroying two nests of pirates; but the merchants, both Chinese and English, fêted us most gloriously, and if it had not been for Mr Reardon we three middies might have always been ashore at dinners and dances.

“But,” cried Barkins, “so sure as one gets an invitation he puts his foot down.”

“Yes,” said Smith; “and it is such a foot.”

“But it’s such a pity,” grumbled Barkins; “for Tsin-Tsin is after all rather a jolly place. Mr Brooke says the ball at the consul’s last night was glorious, no end of Chinese swells there, and the music and dancing was fine.”

“Don’t be so jolly envious, Tanner,” sneered Smith. “You couldn’t have danced if you had gone.”

“Dance better than you could,” cried Barkins hotly.

“No, you couldn’t. Fancy asking a young lady to waltz, and then going dot-and-go-one round the room with your game leg.”

“You’ve a deal to talk about, Smithy; why, if you asked a lady to dance you couldn’t lift your right arm to put round her waist.”

“Couldn’t I?” cried Smith. “Look here.”

He swung his arm round me, took three steps, and dropped on to the locker, turning quite white with pain.

“Told you so,” cried Barkins, springing up. “Waltz? I should just think!—oh, murder!”

He sat down suddenly to hold his leg tightly with both hands, giving Smith a dismal look.

“Oh dear!” he groaned; “what a long time it does take a wound to get well in this plaguey country. I know that knife was poisoned.”

“Nonsense!” I cried, unable to restrain my mirth. “Why, you are both getting on famously.”

“But Dishy might have let us go to the ball last night.”

“Play fair,” I said; “we’ve been out to seven entertainments.”

“Well, what of that? They’ve been to a dozen. It’s all old Dishy’s way of showing his authority. I’m sure we all work hard when we’re on duty, and run risks enough.”

“Go on, you old grumbler. Aren’t we to go up the river shooting on Thursday with Mr Brooke and the doctor?”

“Yes, that’s right enough; but we shall be off again soon on another cruise, and get no more fun for long enough.”

“I say, let’s ask for a run ashore to-day.”

“And get chivvied by the pigtails, same as we did down at that other place.”

“Oh, but perhaps they’ll be more civil here,” I said.

Smith burst out laughing.

“Why, didn’t they pelt you, and shy mud at the skipper?”

“Oh, if you’re afraid, you can stop,” I said. “Tanner and I can go.”

“Afraid!” cried Smith, doubling his fist and holding it within an inch of my nose. “Say afraid again, you miserable insect, and I’ll flatten you.”

“Couldn’t with that hand,” I said, and I caught his wrist.

“Oh, don’t! Murder!” he roared. “I say, you shouldn’t. It’s like touching one’s arm with red-hot iron.”

“Then be civil,” I said.

“Ah, only wait. I say, Tanner, our day’s coming. As soon as we’re both quite strong he has got to pay for all this, hasn’t he?”

“Oh, bother! I say, the skipper and Dishy are both going ashore to-day with an escort of Jacks and marines.”

“Are they?” I said eagerly.

“Yes; there’s some game or another on. Let’s ask leave, and take old Ching with us.”

“Want to try puppy-pie again?” said Smith, grinning.

“I want to do something for a change. I know! I’ll go and see the doctor, and tell him we want a walk in the country to collect flowers, and ask him if he’ll name them.”

“Well, he can’t give us leave.”

“No; but he’ll ask Dishy to let us off.”

“Bravo!” cried Smith. “Off you go. I say, though, we must have old Ching too. You see if he don’t come out in his new gown!”

“What new gown?” I said.

“Hallo! didn’t you know? He went ashore yesterday and bought himself a new blue coat. Not a cotton one, but silk, real silk, my boy, and beckoned me to come and see it,—beckoned with one of his long claws. He’s letting his fingernails grow now, and getting to be quite a swell.”

“Oh yes; old Ching’s getting quite the gentleman. He says he wrote home to his broker to sell the fancee shop. What do you think he said, Gnat?”

“How should I know?” I replied.

“That it wasn’t proper for a gentleman in Queen Victolia’s service to keep a fancee shop.”

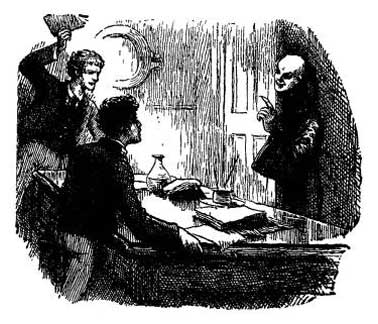

“Murder! Look at that!” cried Smith. “Why, you yellow-skinned old Celestial, you were listening!”

Barkins and I picked up each something to throw at the round, smooth, smiling face thrust in at the door, which was held close to the neck, so that we saw a head and nothing more.

“No flow thing at Ching,” the Chinaman said softly. “Offlicer don’t flow thing. Ching come in?”

“Yes,” said Barkins, “come in. What is it?”

Ching entered looking very important, and gave his head a shake to make his tail fall neatly between his shoulders, and drew the long blue sleeves of his gown over the backs of his hands till only the tips of his fingers, with their very long nails, were visible.

He advanced smiling at us each in turn, and bowing his round head like a china mandarin.

“You all velly good boy?” he said softly.

“Oh yes; beauties,” said Barkins. “What’s up?”

“You likee ask leave go for bit walkee walkee?”

“Don’t!” roared Smith. “Don’t talk like a nurse to us. Why don’t you speak plain English?”

“Yes; Ching speak ploper Inglis. No speakee pigeon Englis. All ploper. Interpleter. You likee go shore for walkee, see something?”

“You beggar, you were listening,” cried Barkins. “How long had you been there?”

“Ching just come ask young genelman likee walkee walkee.”

“Yes, allee likee walkee walkee velly much,” said Barkins, imitating the Chinaman’s squeak. “Why? Can you give us leave?”

Ching shook his head.

“Go ask offlicer. Go for walkee walkee, take Ching; you likee see something velly nice ploper?”

“Yes,” I cried eagerly. “Can you take us to see a Chinese theatre?”

Ching closed his eyes and nodded.

“You come ’long o’ Ching, I showee something velly nice ploper.”

“All right,” I cried. “Now, Tanner, go and try it on with the doctor.”

“No, no. Ask offlicer. Doctor only give flizzick. Velly nastee. Ugh!”

Ching’s round face was a study as he screwed it up to show his disgust with the doctor’s preparations.

Barkins went off and returned directly.

“Well,” we cried; “seen Price?” and Ching, who was squatted on the floor, looked up smiling.

“No.”

“Not seen him?”

“No; I ran against Dishy, and thought I’d ask him plump.”

“And you did?”

“Yes.”

“What did he say?”

“I know,” cried Smith; “that we were always going out.”

“That’s it exactly.”

“And he won’t let us go?” I said in a disappointed tone.

“Who says so?” cried Barkins, changing his manner. “The old chap was in splendid fettle, and he smiled,—now, now, don’t both of you be so jolly full of doubts. On my honour as an officer and a gentleman, he smiled and clapped me on the shoulder.”

“Yes, my lad, of course,” he said. “We shall be off again soon, and then it will be all work and no play again, and we mustn’t make Jack a dull boy, must we?”

“He’s going off his head,” said Smith.

“Let him go, then,” I cried, “if it makes him like this.”

“Don’t chatter so, Gnat,” cried Smith. “I say, did he really say we might go?”

“Yes; and that we ought to start at once before the day grew hotter, and that we were to take great care of ourselves.”

“Hurra!”

“And be sure and wash our faces and our hands before we started,” added Barkins.

“Get out; I can see where it joins,” I cried. “But did he say any more?”

“Only that we were to mind and not get into any trouble with the people, and that we had better take Ching.”

“Yes,” said that individual gravely. “Much better take Ching. Velly useful take care.”

“To be sure,” I cried, full of excitement at the idea of a run through the mazes of the quaint town, and the prospect of seeing a Chinese performance. “I say, Ching,” I cried, striking an attitude, “take us where you can give us a tune, ‘Ti—ope—I—ow.’”

“Yes; velly nicee music,” he said, nodding and smiling. “Ching takee see something velly good. You leady?”

“In five minutes,” cried Barkins. “Gnat, go and tell them to have the boat ready. Mr Reardon said we were to be rowed ashore.”

“Ching leady in five minutes,” said the interpreter, running towards the door.

“Eh? Why, you are ready,” said Smith.

“No. Go put on new blue silk flock. Leady dilectly.”

Ten minutes later we were being rowed ashore, to be landed at the wharf where we met with so unpleasant an attack a short time before. But there was no mob of idlers there now, and we stepped ashore, leaving the good-natured-looking crew smiling at us, and giving the shops many a longing look, as they pushed off and began to row back at once.

“Plenty time,” said Ching. “You likee fust go lestaulant—eatee, dlinkee, spend plize-money?”

“Can’t spend what we haven’t yet got, Ching,” said Barkins. “What do you say, lads? I’m hungry again, aren’t you?”

Smith sighed.

“I’m always hungry,” he said.

“Of course you are. I believe he’s hollow all through, Gnat. How do you feel?”

“As if I haven’t had any breakfast,” I said earnestly.

Ching smiled.

“Velly much nicee bleakfast all along o’ Ching.”

He led the way in and out among the narrow streets, apparently again as much at home as in his own city; and it was hard work to keep from stopping to gaze at the hundreds of objects which attracted and set me longing to make purchases to take home for curiosities. But Ching bustled us along.

“No time now. Come along get good bleakfast. Wantee good bleakfast before go to see gland show.”

“Here, what is it you are going to take us to see, Ching?” cried Barkins—“all right; I wasn’t talking to you,” he added, as a couple of Chinamen turned round to gaze at the young outer barbarian.

“You waitee,” cried Ching, smiling; “all velly ploper gland. You likee see the show.”

“Oh, all right. Where’s the restaurant?”

“Nex’ stleet,” said Ching; and after a few minutes he turned into a showy-looking eating-house, where his blue silk gown and long nails seemed to command the most profound respect from the attendants; and where, after laying down the law very stringently to Ching, that we were to have neither dog, cat, nor rat, we resigned ourselves to our fate, and ate birds’-nest soup, shark-fin, and a variety of what Barkins called messes, with midshipmen appetites.

Ching smiled, and seemed to be very proud of our performance.

“You all eat dlink velly much,” he said, as we gave up, defeated. “You all velly quite full?” he said, rubbing his hands carefully, so as not to injure his long nails.

“Yes, full up, and the hatches battened down,” cried Barkins. “Now then, ask for the bill. How much apiece?”

Ching smiled and nodded his head.

“You come have bleakfast ’long o’ Ching. Ching velly glad to see you; Ching pay.”

“What? nonsense!” cried Smith, while we others stared.

“Yes; Ching plenty money. Captain gave Ching plenty plize-money; make him velly happy to see young offlicer to bleakfast.”

“Oh, but we can’t let him pay for us, Smithy,” cried Barkins.

“No, of course not,” we chorussed.

“Ching velly much hurt you want to pay,” he said, with dignity.

“But—” I cried.

“You ask Ching bleakfast like Chinese genelman another time, make Ching velly glad. Come along, makee haste, see gland show.”

“But the bill isn’t paid,” I cried.

“Ching pay long time ’go,” he said, rising; and there was nothing for it but to follow him out and along three or four streets to where there was a dense crowd in front of a gateway in a high mud wall.

There were some soldiers there too, and Ching walked up full of importance, showed them some kind of paper, when one, who appeared to be their officer, spoke to those under him, and they cleared a way for us to pass to the gate.

Here Ching knocked loudly, and the gate was opened by another soldier; the paper was shown; and an important-looking official came up, looked at us, and made way for us to enter.

“It’s all right,” said Smith. “Ching knows the manager. It will be a private box.”

The official pointed to our left, and Ching led the way behind a kind of barricade where there were seats erected, and, selecting a place, he smilingly made us sit down.

“Ching know gleat mandalin,” he said. “Askee let come see gland show.”

“But what’s it going to be?” I asked, as I looked curiously round the square enclosure surrounded by a high wall, and with seats and pens on three sides. “I thought we were coming to a theatre!”

“No,” said Ching, smiling. “Velly gland show; wait.”

We waited, and saw that the space in front of us was neatly sanded, that posts stood up here and there. In other places there were cross bars, and in two there were ropes hanging.

“I know!” cried Barkins; “he needn’t make such a jolly mystery of it. It’s Chinese athletic sports. Look, there’s the band coming.”

He pointed to a military-looking party marching in with drums, gongs, and divers other instruments; and almost at the same time quite a crowd of well-dressed people entered, and began to take the different places reserved behind the barriers.

Then a body of soldiers, with clumsy spears and shields, marched in and formed up opposite the band, the place filling up till only the best places, which were exactly opposite to us, remained empty.

“You’re right, Tanner,” said Smith just then; “but they’re military athletic sports. I say, here come the grandees.”

For in procession about twenty gorgeously-arrayed officials came marching in, and the next moment I gave Barkins a dig in the ribs.

“Look,” I said.

“All right; I see. Well, we needn’t mind. But I say, what a game if we hadn’t got leave!”

“I say,” whispered Smith, “look over there. The skipper and old Dishy! This was where they were coming, then; they’ll see us directly.”

“Let ’em,” said Barkins, as the party settled themselves. “Now then, we’re all here. All in to begin. We ought to have a programme. Here, Ching, what’s the first thing they do?”

“Ching no quite sure; p’laps lichi.”

“Lichi?” I said.

“You don’t know? You see velly gland—velly ploper for bad, bad man.”

He turned away to speak to a Chinese officer close at hand, while we began to feel wondering and suspicious, and gazed at each other with the same question on our lips.

Ching turned to us again, and I being nearest whispered—

“I say, what place is this? What are they going to do?”

“Bring out allee wicked men. Choppee off head.”