Chapter 22 | Fresh Danger | Blue Jackets

“They’re a long time sending those boats, Herrick,” said the lieutenant to me soon after we had finished our meal.

“It’s rather a long way, sir,” I ventured to suggest.

“Oh yes, it’s a long way; but with the state of dishipline to which I have brought the Teaser they ought to have been here by now. Suppose we were surrounded by the enemy, and waiting for their help to save us!”

“We should think it longer than we do now, sir.” Mr Reardon turned to me sharply, and looked as if in doubt whether he should treat my remark as humorous or impertinent. Fortunately he took the former view, and smiled pleasantly.

“So we should, Herrick, so we should. But if they knew it was to fetch all this loot on board, they’d make a little more haste.”

“They know it by this time, sir,” I said. “They must have met the first boat.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said rather sourly. “The men are very slow when I am not there.”

“Here they are, sir!” I cried; for the marine sentry down by the river challenged, and then there was a loud cheering, and soon after Mr Brooke appeared, followed by a long train of fully-armed Jacks.

“Why, I thought when we started that we had come to fight,” cried Mr Brooke as he reached us. “We met the two loaded boats. Is there much more?”

“Come and look,” said Mr Reardon; and we went first into one and then the other store, while our party of Jacks communicated our luck to the newcomers, the result being that, as we came out of the second long hut, the men cheered again lustily.

Then no time was lost; and the way in which the crew attacked those two stores of loot was a sight to see. It was tremendously hot, but they laughed and cheered each other as those returning met the laden ones going down to the boats. They would have liked to make a race of it to see which crew could load up their boat first, but Mr Reardon stopped that; and the strength of all was put to work to load one boat and get it off, so that there were two streams of men going and coming; and the first boat was deeply laden in an incredibly short space of time, the men leaving themselves no room to row, but placing the chests amidships to form a platform, and two smaller ones in the bow and stern.

They would have laden the boat more deeply still but for Mr Brooke, who superintended at the side of the creek, while Mr Reardon was at the stores.

Then the first of the boats Mr Brooke had brought was sent off, and by the time the next was loaded one of those we had previously sent off returned.

“Velly plime lot of plize-money,” Ching said to me every time we met; and he toiled away with the rest, his face shining, and while our men grew red he grew more and more yellow. But, in spite of the tremendously hard work of carrying down those loads, the men took it all as a party of pleasure; and when, later on in the day, after boatload after boatload had gone down the creek for hours, I had to go up to Mr Reardon with a message from Mr Brooke, I was astonished to see how the contents of the stores had disappeared.

It was getting close upon sundown when the last load was packed into the longboat. Silk bale, tea-chest, rice-bag, crate, and box, with an enormous amount of indescribable loot, including all kinds of weapons, had been taken aboard; and the men who had come up for fresh burdens began cheering like mad as they found the task was done.

“That will do, my lads; steady—steady!” cried Mr Reardon. “Fall in.”

Bang!

It was not a loud report, only that of the rifle fired by the sentry on the ridge; and immediately the men stood to their arms, and were ready for what promised to be an interruption.

“See the sentry, Mr Herrick?” cried the lieutenant.

“Yes, sir,” I said; “he’s running in fast.”

The next minute the man came up, breathless.

“Strong body of John Chinamans, sir, coming across from over yonder.”

“Time we were off, then,” said Mr Reardon; and, giving the word, we started away at the “double” from before the empty stores and huts, toward the creek.

Our run through the wood, though, was soon brought to a walk, for we overtook the last laden men, and had to accommodate our pace to theirs. But they hurried on pretty quickly, reached the boat just as another empty one returned; the loading was finished, and as soon as the boat was ready, an addition was made to her freight in the shape of a dozen Jacks and marines, and she pushed off just as a loud yelling was heard from the direction of the empty stores.

“They’ll be down on us directly,” muttered Mr Reardon; and we all crowded into the empty boat and pushed off after the loaded one, but had not descended the creek far before we were stopped by the loaded boat, and had to arrange our pace by hers.

“Now for a slow crawl,” I thought, “and they’ll be after us directly.”

A loud bang behind us told that I was right, and the handful of rough slugs in the heavy matchlock flew spattering amongst the leaves overhead, cutting off twigs which fell into the boat.

“Lie down all who can,” cried the lieutenant; and we waited for the next shot, which, to be rather Irish, was half-a-dozen in a scattered volley.

But though the twigs and leaves came showering down, no one was hit; and the coxswain steadily poled us along as fast as the progress of the other boat would allow.

I saw that Mr Reardon was on the qui vive to order a return of the fire; but so far we could not see from whence it came, and it seemed as if nothing could be done but keep steadily on with our retreat.

“They might have given us another half-hour, Herrick,” he said. “I should like to get the boys on board unhurt.”

“Think they can get on ahead, sir?” I whispered.

“I hope not. The forest on each side is so dense that I don’t fancy they can get along any faster than we do. Make haste, my lads, make haste,” he said, almost in a whisper; “we shall have it dark here under these trees before long.”

Crash came another volley, accompanied by a savage yelling, but we were so low down between the muddy banks that again the slugs went pattering over our heads.

“Would you mind passing the word to the other boat, messmate,” said a familiar voice. “Tell ’em not to hurry themselves, as we’re very comfortable.”

“Who’s that? Silence!” cried Mr Reardon.

No reply came to his question, but I could hear the men chuckling.

The next minute they were serious enough, for there was a burst of voices from very near at hand.

“Aim low, my lads,” said Mr Reardon. “You six in the stern-sheets, as near to where the shooting is as you can.”

The rifles were levelled, three of the barrels being passed over our shoulders. Then came the usual orders, and the pieces went off like one.

This silenced our pursuers for a few minutes, during which we continued our progress, snail-like at the best, for the boat in front looked like a slug.

“I’d give the order to them to draw aside and let us pass, Herrick,” whispered the lieutenant, who now, in this time of peril, grew very warm and friendly; “but—ah, that’s getting dangerous.”

For another volley from very near at hand rattled over us, and was answered by our men.

“What was I going to say?” continued the lieutenant coolly, “Oh, I remember! If we tried to get by them they might take the ground with all that load, and be stuck.”

“And it would be a pity to have to leave that load, sir,” I said.

“Velly best load—allee best silk!” cried Ching excitedly, “Good, velly good plize-money!”

There was a roar of laughter at this, and Mr Reardon cried—

“Silence!”

Then, sharply, “Fire, my lads, if you see any one following.”

“Ay, ay, sir.”

“Yes, it would be a pity,” said the lieutenant thoughtfully; “but it’s tempting. If we could get in front, Herrick, we could tow the load, and it would shelter us all from the firing.”

“Unless they got to be level with us, sir,” I said.

“And—quick! right and left, my lads. Fire!” cried the lieutenant; for there was the breaking of undergrowth close at hand on either side, and a savage yelling commenced as our pursuers forced their way through.

The men, who had been like hounds held back by the leash, were only too glad to get their orders; and in an instant there was quite a blaze of fire from both sides of the boat, the bullets cutting and whistling through the thick trees and undergrowth; and the movement on the banks, with the cracking and rustling of the bushes and tufts of bamboo, stopped as if by magic.

“Cease firing!” cried Mr Reardon; and then, as if to himself, “Every shot is wasted.”

I did not think so, for it had checked the enemy, who allowed us to go on slowly another hundred yards or so.

“Allee velly dleadful,” whispered Ching to me, as he crouched in the bottom of the boat. “You tinkee hit Ching?”

“I hope not,” I said. “Oh no; we shall get out into the river directly.”

“No,” he said; “velly long way yet.”

“But who are these?” I said—“some village people?”

“Pilate,” he cried. “Allee come home not kill, and findee plize-money gone. Makee velly angly. Wantee chop off sailor head.”

“Like to catch ’em at it,” growled Tom Jecks, who had been very silent for some time.

“Silence there!” cried Mr Reardon sternly. Then to me, “We seem to have checked them, Herrick.”

At that moment there was a sudden stoppage in front, and our coxswain growled—

“Starn all!”

“What is it?” cried Mr Reardon, rising.

There was a rattle of matchlocks from our right, and Mr Reardon fell sidewise on to me.

“Hurt, sir?” I cried in agony.

“Yes, badly—no—I don’t know,” he cried, struggling up with his hand to his head. “Here! why has that boat stopped?”

His voice was drowned by the reports of our men’s rifles, as they fired in the direction from which the shots had come; and just then a voice from the laden boat came through the semi-darkness—

“Ahoy!”

“Yes; what is it?” I said, as I saw that a man had crawled over the stack-like load.

“There’s a gang in front, sir; and we’re aground.”

“And the tide falling,” muttered Mr Reardon. “Herrick, I’m a bit hurt; get our boat close up; half the men are to come astern here, and check the enemy; the other half to help unload and get enough into our boat to lighten the other.”

“Yes, sir,” I said; and I gave the orders as quickly and decisively as I could.

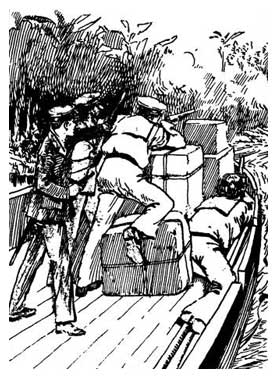

The men responded with a cheer; and, with scarcely any confusion, our boat’s head was made fast to the other’s stern, and the men swarmed on to the top of the load, and began to pass down the bales rapidly from hand to hand.

Crash came a ragged volley from right ahead now; but this was answered by three rifles in the stern of the laden boat, and repeated again and again, while the strong party in the stern of ours kept up a fierce fire for a few minutes.

It was a perilous time, for we knew that if the enemy pushed forward boldly we should be at their mercy. They could come right to the edge of the bank unseen, so dense was the cover; and, working as our men were at such a disadvantage in the gloom, which was rapidly growing deeper, there was no knowing how long it would be before the first boat was sufficiently lightened to float again; it even seemed to be possible that we might not keep pace with the fall of the tide, and then perhaps we should also be aground.

“Hurt much, sir?” I said to Mr Reardon, who was now seated resting his head upon his hand.

“Don’t take any notice of me, my lad,” he said, pressing my hand. “Hit by a bullet. Not very bad; but I’m half stunned and confused. The men and boats, Herrick; save them.”

“If I can,” I thought, as I hurried forward again, and gave orders to the men to pass the silk bales that were nearest to the bows.

“Ay, ay, sir,” they shouted, as readily as if I had been the captain.

From here I went back to the stern, where I found that Mr Reardon was seated now in the bottom of the boat, supported by Ching, while the men were keeping up a steady fire at every spot from which a shot or yell came.

“We’re hard at it, sir,” said Tom Jecks, who was handling his rifle as coolly as if it had been a capstan bar; “but I don’t think we’re hitting any of ’em. How’s the first luff seem?”

“I don’t know,” I said excitedly.

“Well, sir, we’re all right,” said the man, “and are doing our best. You needn’t stop if you can hurry the boys on forward.”

It was a fact; I could do no good at all, so I hurried forward again. But even here I could do nothing; the men had their task to do of lightening the first boat, and they were working as hard as if they had been lying down in the shade all day, and just as coolly, though every now and then the rough slugs the pirates fired from their clumsy matchlocks went spattering through the trees overhead and sent down fresh showers of leaves and twigs.

But I was obliged to say something, and I shouted first one order and then another.

“That’s your sort, lads,” cried a cheery voice. “Down with ’em, and I’ll stow. It’s like bricklaying with big bricks.”

“Who’s that?” I said sharply, for the man’s back was towards me, and it was getting quite dark where we were.

“Me it is, sir—Bob Saunders, sir. Beg pardon, sir.”

“Yes; what is it?”

“Tide’s going down very fast, sir, arn’t it?”

“Yes; why?”

“’Cause we don’t seem to get no forrarder. Hi! steady there! D’yer want to bury yer orficer?”

“Never mind me, man. Stow away; she must soon be lightened enough to make her float.”

“Then we’ll lighten her, sir; but don’t you go and give orders for any of the stuff to be chucked overboard. It’s too vallerble for that.”

“Only as a last resource, Bob,” I replied.

“Beg pardon, sir.”

“Don’t,” I cried to the man who touched me. “Never mind ceremony now; go on firing.”

“Yes, sir; but Tom Jecks says, sir, would you like six on us to land and have a go at the beggars?”

“No,” I cried. “Keep together; we may be afloat at any moment.”

“Right, sir; on’y we’re all willing, if you give the word.”

“I know that,” I cried. “But be careful, my lads. It’s a terrible position, with our chief officer down like this.”

“So it is, sir,” said the man, taking careful aim at a part of the bank where he thought that he saw a movement. Then, almost simultaneously, there was a flash from the place, and another from his rifle muzzle.

“Either on us hit?” he said coolly, as I clapped my hand to my ear, which felt as if a jet of cold air had touched it. “Don’t think I touched him, sir, but he has cut off. I can hear him going. Not hurt, are you, sir?”

“No; a bullet must have gone close to my ear,” I said.

“Oh yes; I felt that, sir. It went between us. But it’s no use to take no notice o’ misses.”

“Well?” I said; for one of the men behind me now touched my arm, and I found it was Bob Saunders.

“We’re getting dead down at the head, sir; hadn’t we better begin stowing aft?”

“Yes, yes, of course,” I said excitedly, and feeling annoyed that I had not thought of this myself.

“Then, if you’ll make the lads ease off to starboard and port, sir, we’ll soon pack a row of these here little bales between ’em. Or look here, sir! how would it be to bring ’em a bit amidships, and let us begin right astarn, and build up a sort o’ bulwark o’ bales? They could fire from behind it when we’d done.”

“Yes, capital!” I cried, once more annoyed with myself because I, a mere boy, had not the foresight of an experienced man.

“No, no,” I cried the next moment. “How could we get at the tiller?”

“You won’t want no tiller, sir; we can row aboard easy enough, once we get out o’ this fiddling little drain.”

“You are right, Saunders,” I said. “Go on.”

All the while the men astern were keeping up a steady fire, which certainly had one effect, that of checking the enemy’s advance. And now Saunders came aft with a bale on his head, keeping his balance wonderfully as he stepped over the thwarts.

“Mind yer eye, Pigtail,” he cried.

“Keep back! Where are you coming?” growled a man who was loading.

“Here, matey,” cried Saunders; and he plumped the bale down right across the stern.

“Hooroar!” cried Tom Jecks, stepping behind it, and resting his rifle on the top.

No more was said, the men easing off out of the way as bale after bale was brought and planted in threes, so that when six had been placed there was a fine breast-work, which formed a splendid protection for those in the stern, and this was added to, until we were fairly safe from enemies behind. But once more we could hear them creeping nearer through the bushes on our right; the firing grew more dangerous, and there was nothing for it, I felt, but to order every man in the two boats to take his piece, shelter himself behind the bales, and help to beat the enemy back.

It was a sad necessity, for I knew that the tide was falling very fast, and that before long we should be immovable; but to have kept on shifting the load and allow the enemy to get close in over our heads on the densely-clothed sides of the stream would, I knew, be madness; and the men showed how they appreciated the common-sense of the order by getting at once under cover, and then the sharp rattle of our fire was more than doubled.

But, enraged by their defeat, and doubly mortified to find that we had discovered their treasure, the pirates seemed now to have cast aside their cowardice, and were creeping in nearer and nearer, yelling to each other by way of encouragement; and, in addition to keeping up an irregular fire, they strove, I suppose, to intimidate us by beating and making a deafening noise on gongs.

“They will be too much for us,” I thought, when we seemed to have been keeping up the struggle for hours, though minutes would have been a more correct definition; and, with the longing for help and counsel growing more and more intense, I was about to kneel down and speak to Mr Reardon, and ask him to try and save himself.

But I started to my feet, for there was a louder yelling than ever, and the pirates made quite a rush, which brought them abreast of us.

“Cutlasses!” I cried; and there was the rattle made in fixing them, bayonet fashion, on the rifles, when—boom!—thud!—came the roar of a heavy gun; there was a whistling shrieking in the air, and then somewhere overhead an ear-splitting crash, followed by the breaking of bushes and trampling down of grass and bamboo.

Then perfect silence, followed by a cheer from our men.

“Well done, Teaser!” shouted Tom Jecks.

It was a diversion which, I believe, saved us, for the enemy fled for some distance, and gave us time to go on lightening the foremost boat.

But before we had been at work many minutes there was a cheer from close at hand, and upon our answering it, another and another, with splashing of oars, and the next minute I heard Mr Brooke’s voice from beyond the first boat.