Chapter 6 | Our Soldier Boy

The sun shone down hotter and hotter, and all was still but the twittering of a bird at times. Dick took the blanket he had wrapped about him overnight and spread it over two pieces of rock so as to form a screen, propping it a little with a broken bough or two. So long as he was busy doing little things for the Colonel, Dick did not seem to mind so much, but just when the sun was highest and it was hotter than ever in the valley, the poor Colonel grew more feverish. He asked for water often, and then all at once the boy felt frightened, for the wounded man began to talk and mutter wildly: then he began to shout to his men to come on and charge, and at last poor Dick broke down. Hunger, misery, loneliness and the heat, were too much for him: the wild nature of the Colonel’s words, and his fierce look when he felt for and waved his sword, making the little fellow shrink away and go and sit behind a stone, his head aching, and the terrible solitude there amongst the mountains seeming more than he could bear.

But as the evening came on and a soft breeze sprang up, a change came over the wounded man, and Dick heard himself called.

He crept back to the Colonel’s side, and the wounded man took his hand, and he said, “Can you be brave and strong?”

“No, sir,” faltered the boy, with his lip quivering, “but I’ll try to be.”

“That is being brave, my boy. Now look here, I have been asleep, and dreaming wild things, but I am cool and calm now. Listen to me. You are faint and hungry, and you must not stay here any longer. You must go.”

“But I can’t leave you all alone, sir.”

“You must, my boy. Here is what I want you to do. Throw the blanket over me and fill the tin with water.”

The boy did this and felt better, for it kept off the feeling of misery.

“That is good,” said the Colonel. “Now start off at once down the valley, and if you see any of the French soldiers before you, strike off to left or right and try and get by them, and don’t go down to the track again till they are left behind.”

“And then find our men, sir?” cried the boy excitedly.

“Yes.”

“And tell them where you are, and bring some back to carry you to your tent?”

“Yes,” said the Colonel, smiling.

“But suppose I can’t find them, sir?”

“Then—” said the Colonel, looking sadly at the boy, before closing his eyes, “then—we won’t talk about that, my boy: a brave little fellow like you must find them.”

“Yes, I’ll try,” said Dick eagerly. “When shall I go?”

“Now,” said the Colonel, and the boy dashed off at once among the rocks and bushes, but in five minutes he was back again.

“What, boy, do you give it up?”

“No,” said Dick stoutly. “I was in such a hurry I didn’t say good-bye, sir—and—and—”

“Well, what?” said the Colonel, smiling, for the little fellow stopped.

“I was afraid!”

“Afraid?”

“You’d think I didn’t mind, and wanted to get away and leave you.”

“But you do not, my boy?”

“Only to find someone to help you.”

The Colonel caught his hand and drew him down closer and closer till he could kiss him, when the tears started to Dick’s eyes and he flung his arms round the wounded man’s neck and clung to him and kissed him in return.

“Now go, Dick,” said the Colonel. “I have just such a little fellow at home in England, and I want to see him again.”

“Have you?” cried Dick eagerly: “then I will find our men so that you shall.”

“Hah,” sighed the Colonel as Dick started off, and he watched the boy till he disappeared. Then he sighed again, drew the blanket more over him and closed his eyes, and as the sun went down and the darkness fell he sank into a deep sleep.

It was just beginning to get dusk the next evening and the sentries about the little hill where the 200th lay had been doubled. For the French regiments not many hundred yards away had crept in closer, and were so placed that the English were surrounded, and their case was very desperate, for though they had plenty of water their provender was getting low, and the scouts sent out had reported to the Major that it looked as if an attack was going to be made.

So the wounded had been placed together behind a rough wall built of pieces of rock, and the men stationed, all hungry and desperate, ready to meet the enemy when they came and drive them back.

“And oh, dear! It’s weary work,” said Mrs Corporal, who had had nothing to cook for the men, but made up for it by acting as nurse and helping the wounded.

She was kneeling down by Corporal Beane when she spoke, and had been trying to comfort him, for he had done nothing but growl because the doctor said he must not think of getting up, and as she talked to him she said suddenly: “Oh, if I could only know what has become of my boy.”

She stopped short, for at that moment a shot was fired, and Corporal Beane sat up and reached for his musket.

“Here they come,” he cried. “I don’t care what the doctor says—I won’t lie here. Give me my cartridge-box, old woman: I’m going to fight.”

There was another shot, close at hand, and then a shrill voice rang out:—“Oh, don’t shoot—don’t shoot!”

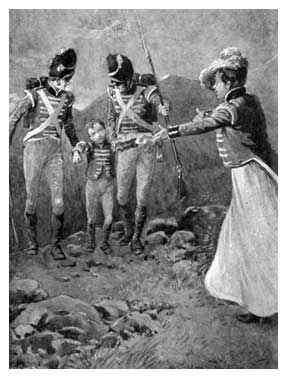

“My boy Dick!” shouted Mrs Beane, and she rushed out, as torn and bleeding, the boy staggered up between two of the men, and the next minute was surrounded by the officers, but could not speak for exhaustion: but he made signs for water, drank some thirstily, and one of the sentries stated to the Major that he had seen something crawling up towards his post and fired.

“And then I see it, and fired too, sir,” said the other.

“Poor boy,” cried the Major. “Where are you hurt?”

“I don’t know—everywhere. I’m scratched, and I tumbled, and my knees are sore. But do go directly, oh! Do go, or he’ll be dead.”

It was some time before in his weak, half-starved state the poor boy could make them understand, for he had completely broken down: and it was not until he had swallowed a little biscuit soaked in wine, as he lay with his head in Mrs Beane’s lap, that he at last told hysterically of how he had managed to crawl by the French outposts and reached his friends.

His last words were, “Why don’t you go?—the Colonel—you’ll be too late.”

There was silence for a few minutes, all present watching the little messenger as he lay back insensible in Mrs Beane’s arms.

Then the Major walked away: the men were formed up in a hollow square: and he addressed them and told them that their Colonel was lying wounded and dying away yonder, on the slope of the ravine, and he called for volunteers to fetch him in.

They stepped forward to a man, and a strong company was told off under one of the captains, the doctor being of the party, and the men carrying a litter ready for their load.

“But we must have the boy for a guide,” said the Major.

There were difficulties in the way, and Mrs Corporal Beane was consulted, for it was evident that Dick was in too exhausted a state to be moved, and she said so as she paused for a few moments in the task of giving him food, a little at a time.

“No, I’m not, sir,” said the boy, to the great surprise of all present. “I can’t walk, but if father came too he could carry me on his back, and I’ll show you the way.”

There was a moment’s silence, and Mrs Corporal sobbed.

“He’s wounded badly, my dear,” she said, kissing him: “but I’m as stout and strong as father is, and I’ll go and carry you.”

“With every man of us to help you,” cried the Captain, and in half an hour’s time, aided by the darkness, the little party stole out of the fortified camp, and by great good fortune passed with Dick’s guidance beyond the enemy’s lines. Then every effort was made, and soon after daybreak the spot where the disastrous fight had been was reached.

It was a sad group which surrounded the motionless figure lying covered with a blanket, which the doctor removed and knelt down; Dick struggling to the other side, while the Captain and his men waited to hear the worst.

“We are not too late,” said the doctor, rising: and after administering stimulants, the words proved true, for the Colonel opened his eyes, looked wildly round, and then smiled as his gaze rested upon Dick, who was holding his hand.

“Thank you, Dick, boy,” he said, in a faint whisper. “I knew you would.”

The cheer which rose from the men made the rocks echo again, and the Captain turned from grasping his old friend’s hand, and said sharply:—

“Silence in the ranks—no, I mean, another cheer, my lads.”

And it was given.

A short halt was made by the pool, while stimulants were administered again to the Colonel, and Mrs Beane insisted on Dick having more, the men eating their scanty rations by the pool. Then the wounded man was carefully laid in the litter so that Dick could lie there too, with his head the opposite way: the men raised their poles, and the march back was begun.

It was just after dark that evening that they were proceeding very cautiously, when there was a sudden outburst of firing.

The Captain needed no telling what was going on, for the long expected attack was being made upon the weakened regiment upon the hill. He did not hesitate, but pressed on with his little band, quite unnoticed by the attacking force, coming upon their rear in the darkness just as they were receiving a check from the brave defenders of the camp, and the Captain poured in volley after volley so unexpectedly that the French broke, and began to retreat before their foes. The Major, grasping what had occurred, turned his defence into a brave attack, and the result was that in a few minutes the enemy was in full retreat, and soon after, this in their confusion became a rout.