Chapter 6 | A Young Hero

“Stop! For pity’s sake,” cried the Doctor. “Don’t fire!”

There was a rush and they were surrounded. Phil was seized roughly by two soldiers, while two more dragged the Doctor to his knees.

“I’ve got a monster, sergeant,” cried one of the men. “Hold still, you wriggling little worm.”

“Let me go,” cried Phil, angrily.

“Now then, who are you?” cried a harsh voice out of the darkness. “Spies from the French camp, sergeant; that’s certain,” said another voice.

“Silence in the ranks!” roared the sergeant. “Now then, sir, what are you?”

“Travellers going south to escape from the war,” said the Doctor, huskily.

“Won’t do,” said the sergeant. “Bad attempt at English. Why, you were speaking in French just now.”

“Yes; I am a French teacher—the tutor to my little pupil here, the son of an English officer.”

“Bah!” cried the sergeant. “What a lame tale. You talked French or some other lingo, and I heard the boy say ‘Oui!’”

“Yes, sir; we talk in French sometimes so that the boy may learn.”

“Oh, indeed! Well, you’re prisoners now, and he shall be taught to speak English. Bring them along.”

“Pardon, sir. You belong to the English force?”

“I rather think we do, mounseer. Search them, my lads. No, wait till we get them to headquarters. What papers have you?”

“Papers, sir?”

“Yes, despatches. Letters.”

“Only my pocket-book,” said the Doctor.

“Got it, sergeant,” said one of the men.

“Nothing else?”

“No, sergeant; not that I can find.”

“Perhaps they’re hidden upon the boy. Like enough.”

Phil soon found that it was vain to resist, and he had to suffer being roughly searched.

“Eh? What’s that?” said the sergeant.

“Says he wants to be taken to his father.”

“Yes, I want to go to my father, to tell him Dr Martin has been taken prisoner by English soldiers.”

“Then you can’t go,” growled the sergeant. “Here, who is your father, young shaver?”

“Captain Carleton, of the 200th Regiment, sir,” said Phil, stoutly.

“The 200th Regiment, eh? I don’t know any Captain Carleton. But bring them along.”

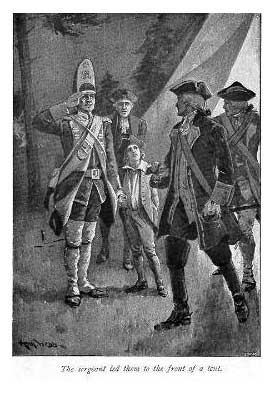

The prisoners were marched off at once through the darkness towards where the fires were burning brightly, and after being challenged again and again, the sergeant led them to the front of a tent, out of which a couple of officers, evidently high in command, came quickly, and were about to hurry away, but stopped for a few moments to listen to the sergeant’s report.

“You are sure they have no despatch upon them?”

“Certain, sir. They have been searched twice.”

“Let them be detained,” said the officer, sharply.

The sergeant marched them off to a large tent, and into this the two prisoners were ushered, to find themselves in company with some half a dozen French soldiers, one of whom lay wounded and in pain upon a truss of straw at the side, the dim light from a lanthorn swinging from the tent pole striking strangely upon the man’s pallid face.

“There you are,” said the sergeant, cheerfully, “and I just give you both warning; there are about a dozen men on duty about this tent with orders to shoot down anyone who tries to escape. Eh, what say?”

“We shall not try to escape; sir,” said the Doctor, quietly; “but that boy—he has been tramping about for hours without food, and is nearly starved.”

“Eh? Poor little chap! Hungry?”

“Yes, sir, dreadfully, and so is Dr Martin.”

“Well, we English don’t starve our prisoners, even if they are French. Wait a bit and I’ll see what I can do,” said the sergeant, with gruff good nature, and he went off, leaving the other prisoners to stare gloomily at the new-comers for a few minutes and then turn their backs to begin talking together, while the Doctor pressed close to his charge and tried to cheer him up.

“It will all come right,” he whispered. “We shall soon be able to send a message to the Captain, and he will have us sent safely away. Are you very hungry now, Phil?”

“Dreadfully,” was the reply. “Do you think the sergeant will be very long?”

“Oh no! He seemed too friendly.”

But the sergeant seemed to Phil as if he had forgotten all about the prisoners, for the time glided slowly on, while weariness began to deaden poor Phil’s hunger pains, and he grew drowsy, nodding off twice, but starting up again when the French prisoners spoke more loudly or a sharp challenge was heard outside.

But the sergeant was a man of his word, and just as Phil was dozing off again, and the lanthorn seemed to be dying out, he suddenly entered the tent with a loaf under his arm and a piece of cold boiled bacon and a knife.

“There you are,” he said, gruffly, “and a nice job I’ve had to get it. Eat away, youngster, and thank your stars you haven’t swallowed musket balls for sugar-plums as you came here. You ought to be ashamed of yourself, old man,” he continued, turning to the Doctor, “for bringing a boy like that amongst all this gunpowder, treason and plot. No, no; I don’t want to hear you talk. Eat your supper. I’ve something else to do.”

Dr Martin sighed as the sergeant swung out of the tent.

“Wait till father comes,” said Phil, “and I’ll tell him all that the sergeant said. I suppose he can’t help being so stupid as to think we are spies and wanted to come here.”