Chapter 3 | Harry Paul’s Present | A Terrible Coward

Zekle Wynn already had his hand upon the door when, mastering the strange feeling of dread that had seized him, Mark Penelly caught him by the arm and held him tightly:

“Look here, Zekle,” he said hoarsely; “that was all a bit of fun—a joke; but I don’t want anyone to know. I’ll give you fifteen pounds if you’ll hold your tongue.”

“No,” said Zekle, stoutly; “it’s my duty to tell, and I’m agoing to tell.”

“Twenty pounds,” cried Penelly.

“No, I said afore that I wouldn’t do it for twenty pounds,” said Zekle, with a very virtuous shake of the head; and as he made an effort to get away, Penelly, who felt desperate, offered him twenty-five pounds.

“Yes, twenty-five pounds, Zekle; I’ll give you twenty-five,” he cried.

“It ain’t no use to try and tempt me, Mas’r Mark—it ain’t indeed. I didn’t ought to hold my tongue about it. No, I’ll go and do my duty.”

“But it will nearly drive my father mad,” said Penelly imploringly; while Zekle’s little sharp eyes twinkled as their owner wondered whether his victim could muster twenty-five pounds.

“I’m very sorry, of course,” said Zekle; “but you see a man must do his duty. No, no, Mas’r Mark, you mustn’t tempt me.”

“I’ll get you the money at once, Zekle,” said Penelly, who saw that his visitor was trembling in the balance—that is, he appeared to be; but Zekle had make up his mind to have twenty-five pounds down before he entered the house.

“I didn’t ought to take it, you know,” said Zekle, hesitating.

“But you will, Zekle, and I’ll never forget your goodness,” said Penelly imploringly; and then hastily locking the door to make sure that his visitor did not go, he went out of the room straight to a desk in his father’s office, which he opened with a key of his own, and returned directly with four five-pound notes and five sovereigns.

“I oughtn’t to take this, Mas’r Mark,” Zekle grumbled; “it ar’n’t my duty, you know; and I wish you’d give me sov’rins instead of them notes.”

“I cannot,” said Penelly sharply. “It has been hard work to get that.”

“Then I s’pose I must take them,” said Zekle, “but it don’t seem like my duty to;” and as he spoke he carefully wrapped up the notes and placed them with the gold in his pocket.

“Now, you’ll swear you’ll never say a word to a soul about this, Zekle.”

“Of course I won’t, Mas’r Mark. But it goes again the grit. I wouldn’t do it for anyone, you know; but as you say it would be hard on your poor father, I won’t tell.”

Penelly bit his lips and said nothing, while Zekle went maundering on about his duty, and how unwilling he was to take the money, till, seeing an awkward look in his victim’s eyes, he concluded that he had better go, and went out, turning at the door to tell Penelly that he might be quite comfortable now, and wishing him good-night.

“Comfortable, you scoundrel!” cried Penelly as soon as he was alone. “I shall never be comfortable till the news comes in that you have been lost overboard in a storm. I’ve been a fool. I was a fool to do such a thing. I only thought it would give him a ducking; and I’m a greater fool to try and bribe that scoundrel. He’ll be always bleeding me now. I’d far better have set him at defiance and bid him do his worst. Bah! I wish I was not such a coward.”

“If I don’t make him pay me pretty heavy for all this,” said Zekle, chuckling to himself, “I’ll know the reason why. Five-and-twenty pounds earned right slap off by just seeing that net pitched overboard! That’s cleverness, that is. Now I’ll just go up to Mas’r Harry Paul and see what he has got to say. P’r’aps there’s a five or a ten to be made there. It’s better than fishing by a long way.”

Harry Paul’s home was a pleasant cottage on the cliff-side, and on Zekle knocking the door was opened by Harry’s widowed mother, who fetched her son and left the two together.

“Ah, Zekle!” cried Harry frankly, as he held out his hand, “I’m afraid I did not half thank you for helping to save my life.”

“Oh! it don’t matter, Mas’r Harry,” said the fellow, smiling and shuffling about.

“But it does matter,” said Harry warmly; “and I am very grateful to you. I am going into Penzance to-morrow, Zekle, and when I come back I’m going to ask you to accept a silver watch to keep in remembrance of what you did.”

“Oh, you needn’t do that, Mas’r Harry,” replied Zekle; “but I thought I’d like to tell you, don’t you know, all about like how it happened. I kinder felt it to be my duty, you see, and then if you liked to say to me, ‘Here, Zekle Wynn, here’s five or ten pounds for you for what you did,’ why you could, you know; but if you didn’t, why it wouldn’t matter a bit, for I always feel as if it was a man’s duty not to take no money ’less he’s earned it.”

“Ah!” said Harry, looking at him with quite an altered expression.

“You see, you don’t know all,” said Zekle mysteriously, as he went softly to the door, peeped out, and then spoke in a whisper.

“Know all!” said Harry. “Why, I know I was nearly drowned.”

“Yes,” said Zekle, going closer to him and taking hold of his pilot jacket, “you was nearly drownded; but how was it?”

“Some of your pile of mackerel net fell overboard and covered me up. It was very careless of you people.”

“Mack’rel nets don’t tumble overboard and nigh upon drownd people without somebody makes ’em,” said Zekle with a cunning leer.

“Somebody makes them!” said Harry with his eyes flashing. “Why, you don’t mean to say that anybody threw that net over me as I swam round!”

“Oh, no!” said Zekle, “I wouldn’t say such a thing of nobody. Oh, no! ’tain’t my duty to go about telling tales.”

“Look here,” said Harry sharply, “if you expect to earn any reward from me, Zekle Wynn, for telling how it was that that net came over me—and I own that it was very strange that it should just as I was swimming by—speak out like a man.”

“Oh, no! I can’t go accusing people of what they p’r’aps didn’t do,” said Zekle; “but look here, Mas’r Harry, have you got any enemies?”

“Enemies! no,” said the young man. “Perhaps Mark Penelly is not very fond of me since we had that quarrel, but I’ve no enemies.”

“Ho!” said Zekle with a peculiar grin. “Who was aboard our boat?”

“I did not see him as I swam up, but I suppose Mark Penelly was there.”

Zekle nodded.

“Yes, and he walked round to the side; and I saw him, as I was shaking out the fish, go and stand by them mack’rel nets.”

“And do you dare to say that he threw them over me?”

“Oh, no!” said Zekle, “I wouldn’t say such a thing of anybody, Mas’r Harry; no, ’tain’t my duty. I wouldn’t accuse no one; but them nets was safe aboard one minute, and the next minute twenty fathom was atop of you; and if we hadn’t hauled you out you wouldn’t have been talking to me just now.”

Harry Paul jumped up and began to walk about the room, his face flushed and his hands twitching.

“Look here, Zekle Wynn!” he said sharply, “I’m plain-spoken, and I like people to be plain-spoken with me. Now, mind what you are saying.”

“Oh, yes! Mas’r Harry, I am very careful what I say, and I’ll go now; but I thought it was my duty to come, and I said to myself, ‘If he likes to say to me, “There’s five or ten pound for you, Zekle Wynn,” why, he could,’ but of course I don’t expect nothing for doing my duty.”

“Oh, you don’t expect anything?” said Harry sharply.

“Oh, no, Mas’r Harry, sir; I never expect to receive anything for doing my duty.”

“And you thought it was your duty to come and tell me that Mark Penelly tried to drown me?”

“Oh, no! Mas’r Harry, sir—oh dear, no! I never said nothing o’ that sort; I only said as the net was in the boat one minute and the next minute it was all over you.”

“Same thing, Zekle,” said Harry sharply. “And you didn’t expect anything for coming and telling me this?”

“Oh dear, no! Mas’r Harry, sir,” replied Zekle.

“Then you’ll be disappointed,” said Harry, smiling pleasantly, “for I shall give you something.”

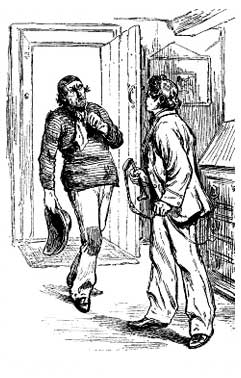

“Oh, thank you! Mas’r Harry, sir,” said Zekle, whose face expanded with pleasure. A moment before he had not liked the way in which Harry had taken his hints; but now this declaration of an intention to give him something was pleasant, and he smiled quite broadly as the young man went to a cupboard.

“Will it be five or ten pound?” said Zekle to himself. “I’m making a good night of it this time, and if I don’t—Don’t you hit me with that there, Mas’r Harry! don’t you hit me with that there!” he roared suddenly. “Don’t you hit me with that there, or I’ll have the law of you.”

“Get out of the place, you contemptible, tale-bearing sneak!” said Harry; and he accompanied his words with lash after lash of a big old-fashioned dog-whip. “How dare you come here with your miserable stories! Out with you, you dog, or I’ll lash you till you are blue!”

There could be no doubt but that some of the strokes administered would leave blue weals, though Zekle did not get many. Four or five fell upon his back and sides, however, before he got out of the door; and he was just turning to shake his fist and vow vengeance when a tremendous lash curled round him, inflicting so much pain that he uttered a loud yell and ran as hard as he could to a safe distance, where he turned once to shout, “Yah, coward!” and then disappeared.

“Coward!” said Harry bitterly. “Well, people say I am. Don’t be frightened, dear,” he continued as his mother entered the room in haste.

“But I am, my dear,” she cried excitedly. “What does all this mean?”

“I only used the dog-whip to a scoundrel—that’s all,” he said, with a reassuring smile; and as soon as he had pacified her he went outside to walk up and down and think about his late escape.

“No,” he said at last after a long thought, during which he had gone well over his adventures that evening; “I will not believe that a man could be such a wretch.”

He felt better after this and went in; but that night the excitement of the adventure and the effects of his immersion were sufficient to keep him awake hour after hour, while when he dropped off into an uneasy slumber it was for his mind to be haunted by dreams in which he was being dragged down into the depths of the sea by a strange monster that clung to his limbs and writhed about him, making him shudder as he felt the chilling embrace.

Again and again he awoke and tried to shake off the unpleasant sensation, but no sooner did he drop off to sleep again than the horrible dream came back, gathering in intensity as the time wore on.

Then came a variation. Mark Penelly was the creature that was trying to drown him; and as he dragged him down and down, lower and lower, into the depths, he kept telling him that it was because he was such a terrible coward, but that if he would dive off Carn Du into a ninth wave he would let him live.

This went on till it grew unbearable, so, leaping out of bed, Harry went to the window, drew up the blind, and threw open the casement, to lean out and gaze at the grey sea, that looked so dark in the early dawn of morning.

It was as smooth as a pond, except where, with a low moan, it heaved up and beat against Carn Du, falling back with an angry hiss as if of disappointment, while all above looked calm and dark and starlit.

Away to the east, though, there was a faint light, telling of the coming day; and as Harry Paul stood there, with the soft fresh morning breeze blowing in his hair, he made up his mind that he would go and fish for three or four hours before breakfast, as he could not sleep.

A good wash made him feel fresher. Then dressing, he took a couple of lines from a cupboard down-stairs, and went out.

He had no difficulty in getting half-a-dozen damaged mackerel down in the harbour—fish that had been torn by the nets; but he was only just in time, for in the soft grey light he could see the gulls already busy floating down on their ghostly-looking wings in the gloom, uttering a mournful, peevish wail, and carrying off fragments of fish for their morning meal.

“Another ten minutes, and there would not have been one left,” muttered Harry, as he strode along the rock-strewn shore to where his boat was drawn up high and dry. He, however, soon had her afloat, and, taking one of the oars, he stood up in the stern and sculled her out with that peculiar fish-tail motion which is so puzzling to one not used to the custom.

Half an hour’s sculling took him out to a great buoy close by some sunken rocks; and having made fast his boat to the rusty, barnacle-encrusted ring, he proceeded to bait his lines, and lowered down the leads into the deep water below.

“What’s it to be this morning?” he said. “They ought to bite on such a tide as this.”

He held one line in his hand, twisted the other round one of the thole-pins of the boat, and then sat waiting. There was black Carn Du right in front, with the waters rising up dark and glistening, to fall back fringed with pale ghostly white.

Then, as no fish bit to take up his attention, he began to think of the great black mass of rock, and to ask himself whether it was worth his while to go that or the next evening, and, climbing up, take the plunge as he had seen so many young men take it before.

“If I did,” he said, “it would please a good many people, and they would no longer look upon me as a coward. I think I could—I feel sure I could. But if I did take the dive how people would triumph after all, and say that I was stung into doing it by what they had said!”

“No,” he added, after a little more consideration; “they may say what they like. I’ll hold to my determination. Coward or no, I’m not going to prove my courage for the sake of gratifying busy tattling people. Better remain a coward all my— Ah, that’s one!”

A sharp snatch at his line, followed by a long peculiar drag, told him what was at his bait; and after a little giving and taking, he drew a heavy twining conger eel over the boat’s edge, having no little difficulty in preventing it from tangling his line, for it was quite a yard in length, and proportionately thick.

His captive was, however, soon safe in the large basket, and he had hardly closed the lid and placed a boulder used as ballast upon it before a tug at his other line made the thole-pin rattle, and after a little hauling he dragged in a gloriously-coloured gurnard, whose outspread fins looked like the wings of some lovely butterfly. Then he drew in, one after the other, a couple of wrasse, all grey and green and gold, with their protuberant mouths and curious teeth, after which there was a pause, and, drawing up one of his lines, Harry placed thereon a much larger hook, bound with wire right up the cord that held it. Upon this he placed quite half a mackerel, secured it well to the hook with a piece of string, and then, throwing it over the side, he waited, after feeling the lead touch the rock below, and wondered whether he should capture what he believed to be lurking amongst the ledges of the piece of rock.

“I may either get a conger or a good hake,” he thought to himself. “There’s always someone glad of a good hake.”

He waited with all a fisherman’s patience, and, used as he was to such scenes, he could not help feeling gladdened at the glorious sight that met his gaze, for, one by one, the stars had paled, till only that named after the morning shone out resplendent in the now grey west; while to eastward all was blushing with bright red and gold and purple and orange, tints so wondrously beautiful and rich that Nature had enough to spare for sea as well as sky. While the latter was growing moment by moment more refulgent, the former caught the wondrous dyes, till the water seemed everywhere like molten gold with ruddy and empurpled reflections where the sea gave a gentle heave. Even the gulls and shags that floated on the tide seemed to be glorified by the wondrous colour, till Harry, as he sat there with the stout cord of his fishing-line twisted round his hand, felt how majestic and awe-inspiring was the coming of the new-born day, and involuntarily exclaimed:

“Who would stay in bed if they knew what the dawn is like on such a morn as this!”

So rapt was he in the grandeur of the scene that he had forgotten all about the object of his journey, but he was brought back to the matter-of-fact present by a tremendous snatch which jerked his arm hanging over the side, and made the cord cut so violently into his hand that he was glad to give the line a twist and set it free to run for some distance before he began to check it a little.

“It’s a monster,” he said, as he felt the struggles of the fish, which dragged so heavily that, to save his line from breaking, as it was, in spite of giving and taking, nearly run out, he cast the boat loose and let it drift as the fish tugged.

It was not big enough to drag it along, but it had some influence on the boat, moving it slowly, and this eased the line, which Harry had hauled upon, so that he kept getting in fathom after fathom ready for the captive’s next run.

This was not long in coming, for after keeping up a steady strain for about a minute, and drawing the fish, whatever it might be, nearer and nearer to the surface, there was a sudden snatch, and away it went again straight for the bottom like an arrow, and then right away.

“The line will break directly,” thought Harry. “It must be either a great conger or a monster hake, or else it’s a small shark. Small!—no, that it isn’t!” he exclaimed as he felt himself steadily drawn along with the current; “I shall never get it.”

Now he was able to haul in a little, the fish coming towards the surface in obedience to his steady drag; now it turned and went off again to the last yard of line, and then the boat was steadily drawn along, while Harry’s wonder was that the strands did not break or the hook drag out.

“This comes of having good new tackle,” he said; and then, “Ah, I must lose it if it pulls like this.”

For the fish made so furious a strain upon the line that he felt that it must break; no such line could bear it.

He felt in despair, for he was all eagerness now to see the monster he had hooked, when a happy thought suggested itself, and in an instant he had made three or four hitches round one of the oars with the end of the line, and cast it overboard.

“There,” he said, “you may tug at that, and I’ll follow you.”

Away went the light oar over the surface, bobbing down at one end, and raising the blade in the air, while, putting the other over the stern, Harry stood up, full of excitement, and began sculling after the novel travelling float, when a wild cry for help, that seemed to send a shudder through his frame, came from behind him over the surface of the sea.