Chapter 26 | Contrabandistas | !Tention

“Think they have gone, comrade?” whispered Punch, after they had listened for some minutes, and the tramp of the French soldiers had quite died away.

“Yes; but speak low. He will come and tell us when he thinks it is safe.”

“All right, I’ll whisper; but I must talk. I can’t bear it any longer, I do feel so savage with myself.”

“Why, what about?”

“To think about that old chap. I wanted to trust him, but I kept on feeling that he was going to sell us; and all the time he’s been doing everything he could for us. But, I say, it was comic to see him carrying you. Here, I mustn’t talk about it, or I shall be bursting out laughing.”

“Hush! Don’t!” whispered Pen.

“All right. But, I say, don’t you think we might have a go at the prog? There’s all sorts of good things in that basket; and I want a drink of water too. But you needn’t have poured a lot of it down my back. I know you couldn’t help it, but it was horrid wet all the same.”

“Don’t touch anything, Punch; and be quiet. He will be coming up soon, I dare say.”

“Wish he’d come, then,” said the boy wearily. “I say, how’s your leg?”

“Hurts,” said Pen curtly.

“Poor old chap! Can’t you turn yourself round?”

“No. It’s worse when I try to move it.”

“That’s bad; but, I say, you see now we couldn’t have gone away unless I carried you.”

“But it seems so unfair to be staying here,” said Pen bitterly. “I believe now I could limp along very slowly.”

“I don’t,” said Punch. “You see, those Frenchies have made up their minds to catch us, and I believe if they caught sight of us creeping along now they would let go at us again; and as we have had a bullet apiece, we don’t want any more.”

“Hist!” whispered Pen; “they think we are here still, and they are coming back.”

“Nonsense! Fancy!”

“Listen.”

“Oh, murder!” whispered Punch. “This is hard!” For he could distinctly hear hurried steps approaching the cottage, and he placed his eye to the knot-hole again to see what effect it was having upon the old man. But he was so still as he crouched there in the lamplight that it seemed as if he had dropped asleep, worn out by his efforts, till all at once the footsteps ceased and there was a sharp tapping on the door, given in a peculiar way, first a rap, then a pause, then two raps close together, another pause, and then rap, rap, rap, quickly.

The old man sprang to his feet, unbarred the door, and seized it to throw it open.

“It’s all over, comrade,” whispered Punch. “Well, let’s fill our pockets with the prog. I don’t want to starve any more.”

He placed his eye to the knot-hole again, and then turned his head to whisper to his companion.

“’Tain’t the Frenchmen,” he said. “It’s one of the Spanish chaps with a red handkercher tied round his head, and him and the old priest is friends, for they are a hugging one another. This chap has got a short gun, and now he’s lighting a cigarette at the lamp. Can you hear me?”

“Yes; go on.”

“There’s four more of them outside the door, and they have all got short guns. One of them’s holding one of them horse-donkeys. Oh, I say, comrade!” continued the boy, as a quick whispering went on and the aromatic, pungent odour of tobacco floated up between the boards.

“What is it, Punch? Oh, go on—tell me! You can see, and I’m lying here on my back and can make out nothing. What does it all mean?”

“Well, I don’t like to tell you, comrade?” whispered the boy huskily.

“Oh yes; tell me. I can bear it.”

“Well, it seems to me, comrade, as we have got out of the frying-pan into the fire.”

“Why, what do you mean?”

“That we thought the old chap was going to sell us to the French when all the time it was to some of those Spanish thieves, and it’s them as has come now to take us away.—Here, wait a minute.”

“I can’t, Punch. I can’t bear it.”

“I’m afraid you will have to, comrade—both on us—like Englishmen. But if we are to be shot for furriners I should like it to have been as soldiers, and by soldiers who know how to use their guns, and not by Spanish what-do-you-call-’ems—robbers and thieves—with little short blunderbusters.”

There was a few moments’ pause, during which hurried talking went on. Then a couple more fierce-looking Spaniards came in, saluted the priest, lit cigarettes at the lamp, and propped the short carbines they carried against the cottage-wall before joining in the conversation.

“What are they doing now, Punch?”

“Talking about shooting or something,” whispered the boy, “and that old ruffian’s laughing and pointing up at the ceiling to tell them he has got us safe. Oh, murder in Irish!” continued the boy. “He’s took up the lamp and he’s showing them the way. Here, Private Gray, try and pull yourself together and let’s make a fight for it, if we only have a shot apiece. They are coming up to fetch us now.”

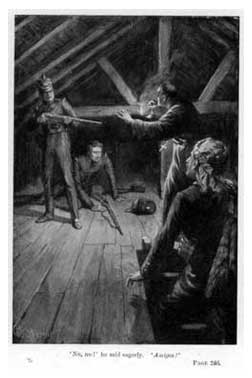

Pen stretched out his hand in the dim loft to seize his musket, but he could not reach it, while in his excitement the boy did not notice his comrade’s helplessness, but seized his own weapon and stood up ready as the light and shadows danced in the gloomy loft, and prepared to give the armed strangers a warm reception.

And now the door at the foot of the ladder creaked and the light of the lamp struck up as the old man began to ascend the few steps till he could reach up, thrusting the lamp he carried before him, and placing it upon the floor, pushing it farther along towards the two boys; and then, drawing himself up, he lifted the light and held it so that those who followed him could see their way.

At that moment he caught sight of Punch’s attitude, and a smile broke out across his face.

“No, no!” he said eagerly. “Amigos! Contrabandistas.”

“What does he mean by that, Pen?”

“That they are friends.”

And the head of the first friend now appeared above the trap in the shape of the first-comer, a handsome, swarthy-looking Spaniard, whose dark eyes flashed as his face was lit up by the priest’s lamp, which shot the scarlet silk handkerchief about his head with hues of orange.

“Buenos Inglés, amigos,” he cried, as he noted the presented musket; and then volubly he asked if either of them spoke French.

“Yes,” cried Pen eagerly; and the rest was easy, for the man went on in that tongue:

“My friend the priest tells me that you have had a narrow escape from the French soldiers who had shot you down. But you are safe now. We are friends to the English. Do you want to join your people?”

“Yes, yes,” cried Pen eagerly. “Can you help us? Are any of our regiments near?”

“Not very,” replied the Spanish smuggler, “for the French are holding nearly all the passes; but we will help you and get you up into the mountains, where you will be safe with us. But our good friend the padre tells me that one of you is badly hurt, and he wants me to look at your wound.”

“Oh, it’s not very bad,” said Pen warmly.

“Ah, I must see,” said the man, who had seated himself at the edge of the opening up which he had come, and proceeded to light a fresh cigarette.

The next moment, as he began puffing away, he seemed to recollect himself, and drew out a cigar, which he offered with a polite gesture to the old priest.

The old man set down the lamp which he had held for his visitor to light his cigarette, and smiled as he shook his head. Then, thrusting a hand into his gown, he took out his snuff-box, made the lid squeak loudly, and proceeded to help himself to a bounteous pinch.

“It is you who have the wound,” continued the smuggler. “You are, I suppose, an officer and a gentleman?”

“No,” said Pen, “only a common English soldier.”

“But you speak French like a gentleman. Ah, well, no matter. You are wounded—fighting for my country against the brigand French, and we are friends and brothers. I have had many a fight with them, my friend, and I know what their bullets do, so that I perhaps can dress your wound better than the padre—brave old man! He can cure our souls—eh, father?” he added, in Spanish—“but I can cure bodies better than he, sometimes, when the French bullets have not been too bad.—Now, father,” he added, “hold the lamp and let us see.”

The priest nodded as he took up the lamp again in answer to the request made to him in his own tongue; and he now spoke a few words to the smuggler which resulted in the picturesque-looking man shaking his head.

“The good father,” he said to Pen, “asks me if I think the French soldiers will come back; but I think not. If they do we shall have warning from my men, who are watching them, for we are expecting friends to meet us here—friends who may come to-night, perhaps many nights hence—for us to guide them through the passes.”

Then, drawing up his legs, he stepped into the loft and called down the stairway to the men below.

There was a short reply, and steps were heard as if the two men had stepped out into the open.

“Now, my friend,” said the smuggler, as he went down on one knee and leaned over Pen, whose hand he took, afterwards feeling his temples and looking keenly into his eyes as the priest threw the light full in the wounded lad’s face.

“Why,” he said, “you are suffering from something else besides your wound. My men will bring some wine. I see you have water here. You are faint. There, let me place you more comfortably.—That’s better. I’ll see to your wound soon.—And you, my friend,” he continued, turning to Punch, who started and shook his head.

“No parly Frenchy,” he said.

“Never mind,” continued the smuggler. “Your friend can.—Tell him to eat some of the bread and fruit, and I will give him some of our grape medicine as soon as my men bring the skin.—A good hearty draught would do you good too, father,” he added, turning to the old man and laying his hand with an affectionate gesture upon the priest’s arm. “You have been working too hard, and must have had quite a scare. I am very glad we have come.”

A deep-toned voice came now from the room below, the smuggler replied, and there was a sound of ascending steps; then another of the smugglers appeared at the opening in the floor, thrusting something so peculiar and strange through the aperture that, as it subsided upon the edge in the full light cast by the smoky lamp, Punch whispered:

“Why, it’s a raw kid, comrade, and I don’t believe it’s dead!”

Pen laughed, and Punch’s eyes dilated as he saw the smuggler, who was standing with his head and shoulders in the opening, take what looked like a drinking-horn from his breast and place it upon the floor; and then it seemed to the boy that he untied a thong that was about one of the kid’s legs, and the next moment it appeared as if the animal had begun to bleed, its vital juice trickling softly into the horn cup, for it was his first acquaintance with a skin of rich Spanish wine.

“There, my friend,” said the smuggler, taking up the half-filled cup, “they say this is bad for fever, but I never knew it do harm to a man whose lifeblood had been drained. Drink: it will put some spirit in you before I perhaps put you to a good deal of pain.” And the next moment he was holding the wine-cup to the wounded lad’s lips.

“There,” said the smuggler at last, as he finished his self-imposed task, “I think you have borne it bravely.”

“Oh, nonsense,” said Pen quietly. “Surely a soldier should be able to bear a little pain.”

“I suppose so,” said his new surgeon; “but I am afraid that some of my countrymen would have shouted aloud at what I have done to you. I know some of my men have when I have tied them up after they have been unlucky enough to get one of the French Guards’ bullets in them. There now, the best thing you can do is to go to sleep;” and, having improvised a pillow for him with one of his follower’s cloaks, the Spaniard descended to the priest’s room, where several of his men were assembled; and after the priest had seen that Punch had been supplied from the basket, he followed his friend to where the men were gathered, leaving the boys in the semi-darkness, for he took down the lamp, whose rays once more shone up through the knot-hole and between the ill-fitting boards.

“Feel better, comrade?” asked Punch. But there was no reply. “I say, you aren’t gone to sleep already, are you?”

Still no answer, and, creeping closer, Punch passed his hand gently over Pen’s arm and touched his face; but this evoked no movement, only the drawing and expiration of a deep breath which came warmly to the boy’s hand as he whispered:

“Well, he must be better or he wouldn’t have gone to sleep like that. Don’t think I could. And, my word, that chap did serve him out!”

The low sound of voices from below now attracted the boy’s attention; and, turning to the knot-hole, he looked down into the priest’s room to see that it was nearly full of the dark, fierce-looking Spaniards, who were listening to the old padre, whose face shone with animation, lit up as it was by the lamp, while he talked earnestly to those who bent forward to listen to his words.

It was a picturesque scene, for the moon was now shining brightly, its rays striking in through the open door and throwing up the figures of several of the contrabandistas for whom there was no room within the cottage, but who pressed forward as if to listen to the priest’s words.

“Why, he must be preaching to them,” said Punch to himself at last, “but I can’t understand a word. This Spanish seems queer stuff. What does el rey mean, I wonder. Dunno,” he muttered, as he yawned drowsily. “Seems queer that eating and drinking should make you sleepy. Well, I ain’t obliged to listen to what that old fellow says. Wonder whether Private Gray knows what el rey means? Better not ask him, though, now he’s asleep. Phew! It is hot up here! Buzz, buzz, buzz! What is he talking about? Seems to make me sleepier to listen to him.—I say, not awake, are you, comrade?”

There was no reply, and soon after Punch’s heavy breathing was heard in addition to the low murmur of the priest’s voice, for the boy too, worn out with what he had gone through during the past hours, was fast asleep.