Chapter 20 | Hunted | !Tention

“What’s the matter, Punch? Wound beginning to hurt you again?”

“No,” said the boy surlily.

“What is it, then? What are you thinking about?”

“Thinking about you being so grumpy.”

“Grumpy! Well, isn’t it enough to make a fellow feel low-spirited when he has been ill for weeks, wandering about here on these mountain-sides, hunted as if we were wild beasts, almost starving, and afraid to go near any of the people?”

“No,” replied Punch with quite a snarl. “If you had had a bullet in your back like I did there’s something to grumble about. I don’t believe you ever knew how it hurt.”

“Oh yes, I did, Punch,” said Pen quietly, “for many a time I have felt for you when I have seen you wincing and your face twitching with pain.”

“Of course you did. I know. You couldn’t have been nicer than you were. But what have you got to grumble about now you’re better?”

“Our bad luck in not getting back to some of our people.”

“Well, I should like that too, only I don’t much mind. You see, I can’t help feeling as jolly as a sand-boy.”

“I don’t know that sand-boys have anything much to be jolly about, Punch,” said Pen, brightening up.

“More do I—but it’s what people say,” said Punch; “only, I do feel jolly. To be out here in the sunshine—and the moonshine, too, of a night—and having a sort of feeling that I can sit down now without my back aching and smarting, and feeling that I want to run and jump and shout. You know what it is to feel better, now, as well as I do. This ain’t home, of course; but everything looks wonderful nice, and every morning I wake up it all seems to me as if I was having a regular long holiday. I say, do say you are enjoying yourself too.”

“I can’t, Punch. There are too many drawbacks.”

“Oh, never mind them.”

“But I can’t help it. You know I have been dreadfully weak.”

“But you shouldn’t worry about that. I don’t mind a bit now you are getting well.”

“What, not when we are faint with hunger?”

“No, not a bit. It makes me laugh. It seems such a jolly game to think we have got to hunt for our victuals. Oh, I think we are having a regular fine time. It’s a splendid place! Come on.”

“No, no; we had better rest a little more.”

“Not me! Let’s get some chestnuts. Ain’t it a shame to grumble when you get plenty of them as you can eat raw or make a fire and roast them? Starve, indeed! Then look at the grapes we have had; and you never know what we shall find next. Why, it was only yesterday that woman gave us some bread, and pointed to the onions, and told us to take more; leastways she jabbered and kept on pointing again. Of course, we haven’t done as well as we did in the hut, when the girl brought us bread and cheese and milk; but I couldn’t enjoy it then with all that stinging in my back. And everything’s good now except when you look so grumpy.”

“Well, Punch, most of my grumpiness has been on your account, and I will cheer up now. If I could only meet some one to talk to and understand us, so that we could find out where our people are, I wouldn’t care.”

“Well, never mind all that, and don’t care. I don’t. Here we are having a big holiday in the country. We have got away from the French, and we are not prisoners. I am all alive and kicking again, and I feel more than ever that I don’t care for anything now you are getting more and more well. There’s only one thing as would make me as grumpy as you are.”

“What’s that, Punch?”

“To feel that my wound was getting bad again. I say, you don’t think it will, do you?”

“No; why should I? It’s all healing up beautifully.”

“Then I don’t care for anything,” cried the boy joyously. “Yes, I do. I feel horrid wild sometimes to think they took away my bugle; leastways, I suppose they did. I never saw it no more; and it don’t seem natural not to have that to polish up. I have got a musket, though; and, I say, why don’t we have a day’s shooting, and knock over a kid or a pig?”

“Because it would be somebody’s kid or pig, and we should be hunted down worse than ever, for, instead of the French being after us for escaped prisoners, we should rouse the people against us for killing their property.”

“Yes, that would be bad,” said Punch; “but it would only be because we are hungry.”

“Yes, but the people wouldn’t study that.”

“Think they would knife us for it?” said the boy thoughtfully.

“I hope not; but they would treat us as enemies, and it would go bad with us, I feel sure.”

“Well, we are rested now,” said Punch. “Let’s get on again a bit.”

“Which way shall we go?” said Pen.

“I dunno; anywhere so’s not to run against the French. I have had enough of them. Let’s chance it.”

Pen laughed merrily, his comrade’s easy-going, reckless way having its humorous side, and cheering him up at a time when their helpless condition made him ready to despair.

“Well,” he said, “if we are to chance it, Punch, let’s get out of this wood and try to go downhill.”

“What for?”

“Easier travelling,” said Pen. “We may reach another pleasant valley, and find a village where the people will let us beg some bread and fruit.”

“Yes, of course,” said Punch, frowning; “but it don’t seem nice—begging.”

“Well, we have no money to buy. What are we to do?”

“Grab,” said Punch laconically.

“What—steal?” cried Pen.

“Steal! Gammon! Aren’t we soldiers? Soldiers forage. ’Tain’t stealing. We must live in an enemy’s country.”

“But the Spaniards are not our enemies.”

“There, now you are harguing, and I hate to hargue when you are hungry. What I say is, we are soldiers and in a strange country, and that we must take what we want. It’s only foraging; so come on.”

“Come along then, Punch,” said Pen good-humouredly. “But you are spoiling my morals, and—”

“Pst!” whispered Punch. “Lie down.”

He set the example, throwing himself prone amongst the rough growth that sprang up along the mountain-slope; and Pen followed his example.

“What can you see?” he whispered, as he crept closer to his comrade’s side, noting the while that as he lay upon his chest the boy had made ready his musket and prepared to take aim. “You had better not shoot.”

“Then tell them that too,” whispered Punch.

“Them! Who?”

“Didn’t you see?”

“I saw nothing.”

“I did—bayonets, just below yonder. Soldiers marching.”

“Soldiers?” whispered Pen joyfully. “They may be some of our men.”

“That they are not. They are French.”

French they undoubtedly were; for as the lads peered cautiously from their hiding-place, and listened to the rustling and tramp of many feet, an order rang out which betrayed the nationality of what seemed to be a large body of men coming in their direction.

“Keep snug,” whispered Punch, “and they won’t see us. It’s too close here.”

Pen gripped his companion’s arm, and lay trying to catch sight of the marching men for some minutes with a satisfied feeling that the troops were bearing away from them. But his heart sank directly after; a bugle-call rang out, the men again changed their direction, the line extended, and it became plain that they would pass right over the ground where the two lads lay.

“I am afraid they will see us, Punch,” whispered Pen. “What’s to be done?”

“Run for it. Look here, make straight for that wood up the slope,” whispered Punch. “You go first, and I will follow.”

“But that’s uphill,” whispered Pen.

“Bad for them as for us,” replied the boy. “Up with you; right for the wood. Once there, we are safe.”

Punch had said he hated to argue, and it was no time for argument then as to the best course.

Pen gazed in the direction of the approaching party, but they were invisible; and, turning to his comrade, “Now then,” he said, “off!”

Springing up, he started at a quick run in and out amongst the bushes and rocks in the direction of the forest indicated by his companion, conscious the next minute, as he glanced back in turning a block of stone, that Punch was imitating his tactics, carrying his musket at the trail and bending low as he ran.

“Keep your head down, Punch,” he said softly, as the boy raced up alongside. “We can’t see them, so they can’t see us.”

“Don’t talk—run,” whispered Punch. “That’s right—round to your left. Don’t mind me if I hang back a bit. I am short-winded yet. I shall follow you.”

For answer, Pen slackened pace, and let Punch pass him.

“Whatcher doing?” whispered the boy.

“You go first,” replied Pen, “just as fast as you can. I will keep close behind you.”

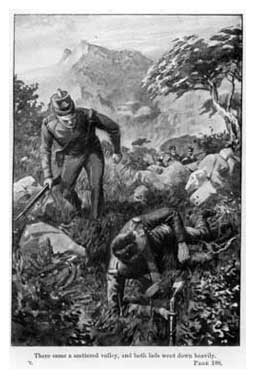

Punch uttered a low growl, but he did not stop to argue, and they ran on and on, getting out of breath but lighter hearted, as they both felt that every minute carried them nearer to safety, for the risky part where the slope was all stone and low bush was nearly passed, the dense patch of forest nearer at hand offering to them shelter so thick that, once there, their enemies would have hard work to judge which direction had been taken; and then all at once, when all danger seemed to be past, there came a shout from behind, and then a shot.

“Stoop! Stoop, Punch! More to the left!”

“All right. Come on,” was whispered back; and, as Punch bore in the direction indicated by his comrade, there came shout after shout, shot after shot, and the next minute, as the fugitives tore on heedless of everything but their effort to reach the shelter in advance, it was perfectly evident to them that the bullets fired were whizzing in their direction.

Twigs were cut and fell; there was the loud spat, spat of the bullets striking the rocks; and then, when they were almost within touch of the dark shadows spread by the trees, there came a scattered volley, and both lads went down heavily, disappearing from the sight of their pursuers, who sent up a yell of triumph.

“Punch,” panted Pen, “not hurt?”

The answer was a hoarse utterance, as the boy struggled to his feet and then dropped again on all-fours.

“No, no,” he gasped. “Come on! come on! We are close there.”

Pen was breathing hard as he too followed his comrade’s movements just as if forced thereto by the natural instinct that prompted imitation; but the moment he reached his feet he dropped down again heavily, and then began to crawl awkwardly forward so that he might from time to time catch a glimpse of Punch’s retiring form.

“Come on, come on!” kept reaching his ears; and then he felt dizzy and sick at heart.

It seemed to be growing dark all at once, but he set it down to the closing-in of the overshadowing trees. And then minutes passed of confusion, exertion, and a feeling as of suffocation consequent upon the difficulty of catching his breath.

Then at last—he could not tell how long after—Punch was whispering in his ear as they lay side by side so close together that the boy’s breath came hot upon his cheek.

“Oh, how slow you have been! But this ’ere will do—must do, for we can get no farther. Why, you were worse than me. Hurt yourself when you went down?”

Pen was about to reply, when a French voice shouted, “Forward! Right through the forest!”

There was the trampling of feet, the crackling of dead twigs, and Punch’s hand gripped his companion’s arm with painful force, as the two lads lay breathless, with their faces buried in the thick covering of past years’ dead leaves, till the trampling died away and the fugitives dared to raise their faces a little in the fight for breath.