Chapter 1 | Miss Diana | Deacon Pitkin's Farm

Thanksgiving was impending in the village of Mapleton on the 20th of November, 1825.

The Governor's proclamation had been duly and truly read from the pulpit the Sunday before, to the great consternation of Miss Briskett, the ambulatory dressmaker, who declared confidentially to Deacon Pitkin's wife that "she didn't see nothin' how she was goin' to get through things—and there was Saphiry's gown, and Miss Deacon Trowbridge's cloak, and Lizy Jane's new merino, not a stroke done on't. The Governor ought to be ashamed of himself for hurrying matters so."

It was a very rash step for Miss Briskett to go to the length of such a remark about the Governor, but the deacon's wife was one of the few women who are nonconductors of indiscretion, and so the Governor never heard of it.

This particular Thanksgiving tide was marked in Mapleton by exceptionally charming weather. Once in a great while the inclement New England skies are taken with a remorseful twinge and forget to give their usual snap of September frost which generally bites off all the pretty flowers in so heart-breaking a way, and then you can have lovely times quite down through November.

It was so this year at Mapleton. Though the Thanksgiving proclamation had been read, and it was past the middle of November, yet marigolds and four-o'clocks were all ablaze in the gardens, and the golden rod and purple aster were blooming over the fields as if they were expecting to keep it up all winter.

It really is affecting, the jolly good heart with which these bright children of the rainbow flaunt and wave and dance and go on budding and blossoming in the very teeth and snarl of oncoming winter. An autumn golden rod or aster ought to be the symbol for pluck and courage, and might serve a New England crest as the broom flower did the old Plantagenets.

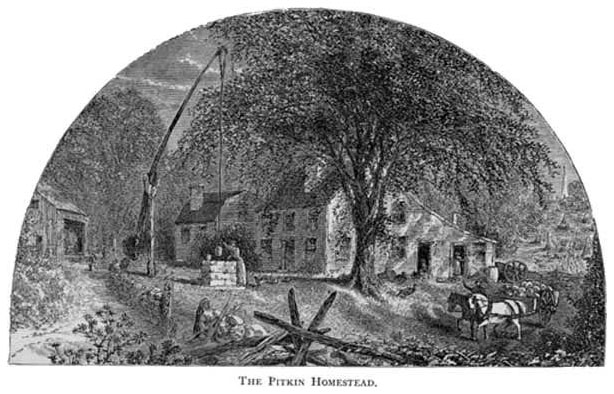

The trees round Mapleton were looking like gigantic tulip beds, and breaking every hour into new phantasmagoria of color; and the great elm that overshadowed the red Pitkin farm-house seemed like a dome of gold, and sent a yellow radiance through all the doors and windows as the dreamy autumn sunshine streamed through it.

The Pitkin elm was noted among the great trees of New England. Now and then Nature asserts herself and does something so astonishing and overpowering as actually to strike through the crust of human stupidity, and convince mankind that a tree is something greater than they are. As a general thing the human race has a stupid hatred of trees. They embrace every chance to cut them down. They have no idea of their fitness for anything but firewood or fruit bearing. But a great cathedral elm, with shadowy aisles of boughs, its choir of whispering winds and chanting birds, its hush and solemnity and majestic grandeur, actually conquers the dull human race and asserts its leave to be in a manner to which all hearts respond; and so the great elms of New England have got to be regarded with a sort of pride as among her very few crown jewels, and the Pitkin elm was one of these.

But wasn't it a busy time in Mapleton! Busy is no word for it. Oh, the choppings, the poundings, the stoning of raisins, the projections of pies and puddings, the killing of turkeys—who can utter it? The very chip squirrels in the stone-walls, who have a family custom of making a market-basket of their mouths, were rushing about with chops incredibly distended, and their tails had an extra whisk of thanksgiving alertness. A squirrel's Thanksgiving dinner is an affair of moment, mind you.

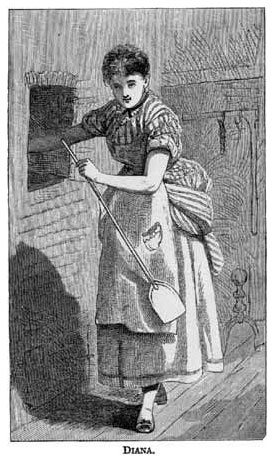

In the great roomy, clean kitchen of the deacon's house might be seen the lithe, comely form of Diana Pitkin presiding over the roaring great oven which was to engulf the armies of pies and cakes which were in due course of preparation on the ample tables.

Of course you want to know who Diana Pitkin was. It was a general fact about this young lady that anybody who gave one look at her, whether at church or at home, always inquired at once with effusion, "Who is she?"—particularly if the inquirer was one of the masculine gender.

This was to be accounted for by the fact that Miss Diana presented to the first view of the gazer a dazzling combination of pink and white, a flashing pair of black eyes, a ripple of dimples about the prettiest little rosy mouth in the world, and a frequent somewhat saucy laugh, which showed a set of teeth like pearls. Add to this a quick wit, a generous though spicy temper, and a nimble tongue, and you will not wonder that Miss Diana was a marked character at Mapleton, and that the inquiry who she was was one of the most interesting facts of statistical information.

Well, she was Deacon Pitkin's second cousin, and of course just in that convenient relationship to the Pitkin boys which has all the advantages of cousinship and none of the disadvantages as may be plain to an ordinary observer. For if Miss Diana wished to ride or row or dance with any of the Pitkin boys, why shouldn't she? Were they not her cousins? But if any of these aforenamed young fellows advanced on the strength of these intimacies a presumptive claim to nearer relationship, why, then Diana was astonished—of course she had regarded them as her cousins! and she was sure she couldn't think what they could be dreaming of—"A cousin is just like a brother, you know."

This was just what James Pitkin did not believe in, and now as he is walking over hill and dale from Cambridge College to his father's house he is gathering up a decided resolution to tell Diana that he is not and will not be to her as a brother—that she must be to him all or nothing. James is the brightest, the tallest, and, the Mapleton girls said, the handsomest of the Pitkin boys. He is a strong-hearted, generous, resolute fellow as ever undertook to walk thirty-five miles home to eat his Thanksgiving dinner.

We are not sure that Miss Diana is not thinking of him quite as much as he of her, as she stands there with the long kitchen shovel in one hand, and one plump white arm thrust into the oven, and her little head cocked on one side, her brows bent, and her rosy mouth pursed up with a solemn sense of the importance of her judgment as she is testing the heat of her oven.

We are not sure that Miss Diana is not thinking of him quite as much as he of her, as she stands there with the long kitchen shovel in one hand, and one plump white arm thrust into the oven, and her little head cocked on one side, her brows bent, and her rosy mouth pursed up with a solemn sense of the importance of her judgment as she is testing the heat of her oven.

Oh, Di, Di! for all you seem to have nothing on your mind but the responsibility for all those pumpkin pies and cranberry tarts, we wouldn't venture a very large wager that you are not thinking about cousin James under it all at this very minute, and that all this pretty bustling housewifeliness owes its spice and flavor to the thought that James is coming to the Thanksgiving dinner.

To be sure if any one had told Di so, she would have flouted the very idea. Besides, she had privately informed Almira Sisson, her special particular confidante, that she knew Jim would come home from college full of conceit, and thinking that everybody must bow down to him, and for her part she meant to make him know his place. Of course Jim and she were good friends, etc., etc.

Oh, Di, Di! you silly, naughty girl, was it for this that you stood so long at your looking-glass last night, arranging how you would do your hair for the Thanksgiving night dance? Those killing bows which you deliberately fabricated and lodged like bright butterflies among the dark waves of your hair—who were you thinking of as you made and posed them? Lay your hand on your heart and say who to you has ever seemed the best, the truest, the bravest and kindest of your friends. But Di doesn't trouble herself with such thoughts—she only cuts out saucy mottoes from the flaky white paste to lay on the red cranberry tarts, of which she makes a special one for each cousin. For there is Bill, the second eldest, who stays at home and helps work the farm. She knows that Bill worships her very shoe-tie, and obeys all her mandates with the faithful docility of a good Newfoundland dog, and Di says "she thinks everything of Bill—she likes Bill." So she does Ed, who comes a year or two behind Bill, and is trembling out of bashful boyhood. So she does Rob and Ike and Pete and the whole healthy, ramping train who fill the Pitkin farm-house with a racket of boots and boys. So she has made every one a tart with his initial on it and a saucy motto or two, "just to keep them from being conceited, you know."

All day she keeps busy by the side of the deacon's wife—a delicate, thin, quiet little woman, with great thoughtful eyes and a step like a snow-flake. New England had of old times, and has still, perhaps, in her farm-houses, these women who seem from year to year to develop in the spiritual sphere as the bodily form shrinks and fades. While the cheek grows thin and the form spare, the will-power grows daily stronger; though the outer man perish, the inner man is renewed day by day. The worn hand that seems so weak yet holds every thread and controls every movement of the most complex family life, and wonders are daily accomplished by the presence of a woman who seems little more than a spirit. The New England wife-mother was the one little jeweled pivot on which all the wheel work of the family moved.

"Well, haven't we done a good day's work, cousin?" says Diana, when ninety pies of every ilk—quince, apple, cranberry, pumpkin, and mince—have been all safely delivered from the oven and carried up into the great vacant chamber, where, ranged in rows and frozen solid, they are to last over New Year's day! She adds, demonstratively clasping the little woman round the neck and leaning her bright cheek against her whitening hair, "Haven't we been smart?" And the calm, thoughtful eyes turn lovingly upon her as Mary Pitkin puts her arm round her and answers:

"Yes, my daughter, you have done wonderfully. We couldn't do without you!"

And Diana lifts her head and laughs. She likes petting and praising as a cat likes being stroked; but, for all that, the little puss has her claws and a sly notion of using them.