Chapter 18 | A Life's Eclipse

“Nay, sir, I don’t know any more about it, and I arn’t a-going to say nowt about it, but if that there poor bairn—”

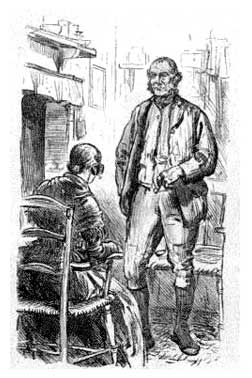

“What poor bairn?” said James Ellis angrily, as he stood in the keeping-room of old Tummus’s cottage. “I was asking you about John Grange.”

“Well, I know you were. Arn’t he quite a bairn to me?”

“Please don’t be cross with him, Mr Ellis, sir,” said old Hannah respectfully; “it’s only his way, sir.”

“Very well, let him go on,” cried James Ellis testily.

“Just you keep your spoon out o’ the broth, mother,” grumbled old Tummus, “I know what I’m about.”

“Well, what was it you were going to say?” asked the bailiff.

“I were going to say as I wouldn’t say nowt about it, and I won’t, but that poor lad has either been made away wi—”

“Tut, tut, nonsense!”

“Well, then, he’s made away wi’ himself,” cried old Tummus, bringing his hand down upon the table with a heavy bang.

The bailiff, who had not removed his hat before now, took it off, showing a heavy dew upon his forehead, which he wiped away as he looked uneasily from one to the other.

“What—what makes you say that, Tummus?” murmured Ellis, who did not seem to be himself at all.

“Now, Tummus, do mind what you’re saying,” said old Hannah, in a lachrymose tone of voice.

“Well, I am, arn’t I? What I say is this: Warn’t it likely?”

“Likely?”

“Aye, likely. Here’s the poor lad loses his sight all at once just when he’s getting on and going to be head-gardener and marry my pretty bairn.”

“Nothing of the sort, sir,” cried the bailiff warmly. “You’re too fond of settling other people’s business.”

“Yes, Mr Ellis, sir, that’s what I tell him,” said old Hannah anxiously.

“Tchah!” growled old Tummus, giving his body a jerk. “Very well then, sir, he thowt he were, and it got on his mind like that he were all in the darkness, and it’s my belief as he couldn’t bear it, and went and made a hole in the water so as to be out of his misery.”

“Oh, Tummus, you shouldn’t!”

“No, no; he was not the man to do such a thing,” said Ellis, whose voice sounded husky, and who looked limp and not himself.

“I dunno,” growled Tummus; “they say when a man’s in love and can’t get matters settled, he’s ready to do owt. I never weer in love, so I doan’t know for sure.”

“Oh, Tummus!” cried old Hannah reproachfully.

“Will ta howd thee tongue?” cried the old man.

“No, I won’t, Tummus. Not even with Mr Ellis here, if you stand there telling such wicked stories.”

“Arn’t a story,” cried the old man, with the twinkle of a grim smile at the corners of his lips. “Who’d ever go and fall in love with an ugly owd woman like thou?”

“It couldn’t be that; no, no, it couldn’t be that,” said the bailiff hastily.

“Wheer is he then, sir?” said old Tummus firmly.

“Gone away for a bit—perhaps to London.”

“Nay, not he,” said old Tummus, shaking his head, “I’m sewer o’ that.”

“Why, how do you know?”

“Would a smart young man like John Grange was ha’ gone up to London without takking a clean shirt wi’ him?”

“What!”

“Didn’t take no clean shirt nor stoggins nor nowt.”

“Are you sure of that?” said the bailiff.

“I couldn’t make out that anything was gone out of his room, sir,” said old Hannah, clapping her apron to her eyes. “Poor dear: it’s very, very sad.”

“Aye, it’s sad enough,” said old Tummus; “not as it matters much, what’s the good o’ going on living?”

“Tummus!” cried his wife.

“Well, what are yow shoutin’ at? I say it again: What’s the good o’ livin’? You on’y get horrid owd, and your missus allus naggin’ you at home, and your Dan Barnetts shoutin’ at you in the garden, or else Master Ellis here giving it to you about something.”

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Tummus,” said his wife. “To go and say such a thing to Mr Ellis’s face, as has allus been a kind friend to you.”

“Aye, lass, I don’t grumble much at he, but we’m do grow precious owd.”

“And a great blessing too, Tummus,” cried his wife. “You don’t hear Mr Ellis complain about getting old.”

“Nay, but then he’s got a pretty bairn, bless her!—as sweet and good a lass as ever stepped; and I says that to Master Ellis’s face, same as I’ve often said it behind his back. Bless her! There!”

James Ellis, with the great care upon his breast—the haunting thought that perhaps, after all, he had had something to do with John Grange’s disappearance—now stood in old Tummus’s cottage a different being. There was none of the rather pompous, important manner that he was in the habit of putting on when addressing his inferiors. The faces of John Grange and Mary seemed to rise before him reproachfully, and, for the first time in his life, he stood before the old couple in the cottage a humbled man, hardly conscious of what was being said.

“Then he took nothing away with him, Hannah?” he said at last.

“No, sir, nothing that I can make out.”

“Nowt!” said old Tummus. “Here he were, hevving his tea that night, looking that down sad, that a bad tater was nowt to him; next thing is as we hears him go out o’ the door—that there door just behind wheer you’re a-standing, Mr Ellis, sir, and he didn’t come back.”

“Didn’t come back,” said the bailiff, repeating the old man’s words.

“We didn’t set up for him because we know’d he’d shut oop all right, and if he didn’t nobody wouldn’t come and steal our plate, ’cause the owd woman allus taks it to bed wi’ her.”

“Tummus!”

“Well, so you do; six silver teaspoons, on’y one was lost years ago, and the sugar bows, sir, she allus wrops ’em up in an owd pocky ankychy.”

“There is no water near,” said James Ellis, as if to himself, but old Tummus’s ears were sharp enough.

“There’s the river.”

“Two miles away, Tummus.”

“What’s two miles to a man who wants to drownd hissen! Why, if I wanted to mak’ a hole in the watter I’d walk twenty.”

“Tummus, I will not have you say such dreadful things.”

“It’s very, very sad, Hannah,” said James Ellis at last; “and I’m more upset about it than I can say, for he was a fine, worthy young fellow, and as good a gardener as ever stepped.”

“That he was,” murmured the old couple.

“But we don’t know that anything so terrible has happened. Some day perhaps we shall be hearing news of him.”

“Nay, you never hear news o’ them as has gone before, Master Ellis, sir. If I were you, I’d have the pond dragged up at the farm, and watter dreened off at Jagley’s mill.”

“No, no,” cried the bailiff hastily. “There is no reason for suspecting such a thing. John Grange was not the man to go and do anything rash. There, I thought I’d come and have a few words with you, Hannah, and you too, Tummus. I want you’ to hold your tongues, now, and to let this sad business die a natural death. You understand?”

“Oh yes, sir.”

“Chatter grows into bad news sometimes. There, good-evening. I dare say you’ll hear news about the poor fellow some day.”

“Nay, we wean’t,” said old Tummus, when the bailiff was gone. “John Grange is as dead as a door-nail, and owd Jemmy Ellis knows it too; but he’s scarred of his bairn hearing, and don’t want the missus up at the house to think on it.”

“But we don’t know that he is dead,” said old Hannah.

“Not for sewer,” growled old Tummus, beginning to take off his heavy boots; “and we arn’t sewer of a many things. But then, owd Jimmy’s as good as master here, and if you go flying in his face you may just as well fly over the garden wall same time. I’ve done, missus. I don’t say who done it, but it’s my belief John Grange was put out o’ the way.”

“Oh, don’t, Tummus; you give me the creeps.”

“All right, all right, I’ve done. It’s a rum world, and everything goes wrong in it.”

“Not quite everything, dear.”

“Well, no, not quite everything, but nearly. I believe it’s because it was made round. Lookye here, missus: how can matters go right on a thing as has got no sound bottom to stand on? If the world had been made square it would have stood square, and things would have come right; but there it is all round and never keeping steady, and allus changing. Why, if you get a fine day you never can count upon another.”

“No,” sighed Hannah; “but there’s a deal of good in the world, after all.”

“Eh? What?” cried old Tummus, jumping up and standing upon the patchwork hearthrug in his stockings, “wheerabouts?—wheer is it, owd woman? I’m a-going to look for it ’fore I gets a day owder.”

“Sit down, and don’t talk such stuff, Tummus,” cried the old woman, giving him a push which sent him back in his chair. “I won’t have it.”

“Ah! That’s it,” he said, with a low, chuckling laugh; “it’s because the world’s round. If it had been square we should all have stood solid, and old women wouldn’t ha’ flown at their mesters and knocked ’em down.”